In March 2025, the Urban Company — an app service based in India — published the following advertisement:

Your maid left you hanging? We leave your home spotless!

InstaMaids at your service in 15 minutes.

Now rebranded as InstaHelp, the pilot service aimed to provide customers with prompt access to domestic labour for just over 50 cents an hour (₹49).1 Urban Company claims that their service would be ‘a step toward formalizing and uplifting’ what is one of the most precarious, unregulated labour sectors in the country, with women making up at least 70% of the workforce.2

However, between 2023 and 2024, Urban Company faced recurring protests by beauty workers — predominantly women — across multiple Indian cities, who rallied against the app’s unethical practices, including ID blocking, price gouging, and unfair contract termination. In one particular case, the worker was eight months pregnant during her contract termination.3

This advertisement — featuring a lavishly dressed woman frowning at a message from a domestic worker in her employ — echoes another one from over half a century ago: never takes a vacation or holiday, never asks for a raise.4 Popularised in 1971 by a Detroit-based temp agency, the Never-Never Girl, a caricature of the ever-expendable worker, is today an archetype that represents up to 12% of the global labour force now known as ‘gig workers’.5

How did this model of hyper-exploitation emerge? How did the decline of a ‘neoliberal’ economic paradigm become an opportunity for entrepreneurs at companies like Uber, Deliveroo, and InstaHelp to accelerate its most pernicious model of labour? And how is it related to the rise of Reactionary International across the world?

The Rise of Platform Capitalism

“Embrace the chaos” - Unnamed Uber executive in Asia, in a message to employees (Uber Files, 2022)

Digital labour platforms, or platform apps, are tech-based intermediaries that connect workers who provide labour services with customers and businesses that demand and supply these services. The workers are engaged on a casual basis, and are compensated per commission or ‘gig’. At the crux of this model lies the ‘independent contractor’ classification, wherein the workers are not legally considered employees of these app companies, but are instead classified as self-employed vendors, which puts the costs of conducting these services — such as vehicle costs, fuel, insurance, licensing — entirely on the workers. Not quite the technological innovation as they are often advertised, platform apps instead heralded the production of a perpetually ‘on demand’ workforce.7 The restructured labour model, which has since mushroomed into a global phenomenon, has its roots in two economic moments in the twentieth century.

In the years immediately succeeding World War II, trade union membership and action in the United States were thriving, with a rise from 13% (in 1935) to 33% (in 1953) membership in non-agricultural employment.8 The late 1940s saw the establishment of a handful of temp agencies, including the Russell Kelly Office Service, the advertisers of the aforementioned Never-Never Girl. To avoid abiding by labour regulations adopted across employer types, these agencies marketed temp work as ‘women’s work’, efficiently carving out a new category of employment that would not fall under the purview of these regulations or union protections. By the 1970s, temp work was a sizable industry, and by the 2000s, there were an estimated 3 million workers a day in temporary employment in the United States.9

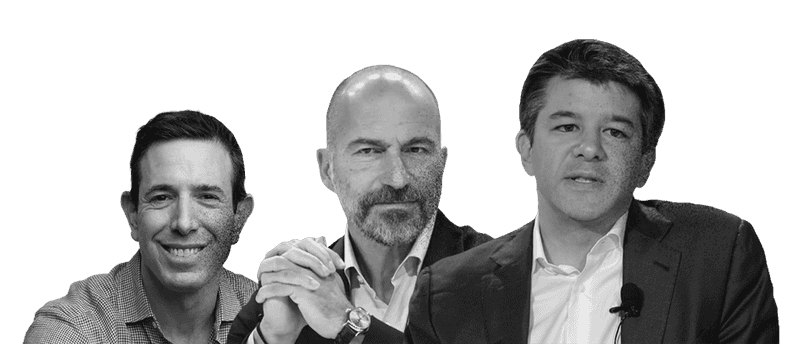

As the economic and political sphere in the West shifted towards neoliberalism in the 1970s, the taxicab industry in the US became one of the first sectors to adapt the temp-work format into an independent contractor model. Using the existing carve-outs in labour laws, and taking advantage of the drivers’ discontent with existing unions, cab companies across the country reorganised their business models to do away with the costs built into traditional employment models. In 1976, companies in San Francisco began pushing for a system wherein drivers could lease their taxis on a per-shift basis.10 Over the next three decades, the leasing model continued to be used by cab companies, with informal workers’ groups pushing back against the lack of security afforded by the model.

While the leasing and independent contractor system of the decades before Uber’s launch formed the foundation for its business model, its technological framework finds precedence in more contemporary software built for smartphones. Launched in 2008, Virginia-based Taxi Magic developed a ride-hailing interface which also allowed customers to pay for their ride through credit cards. The app caught on rapidly across cities in the US, covering more ground than Uber until as late as 2013.11 In 2009, San Francisco-based Cabulous (later rebranded as Flywheel) was adopted by cab companies to transition to a phone-operated system that could facilitate booking, location tracking, and online payments.12

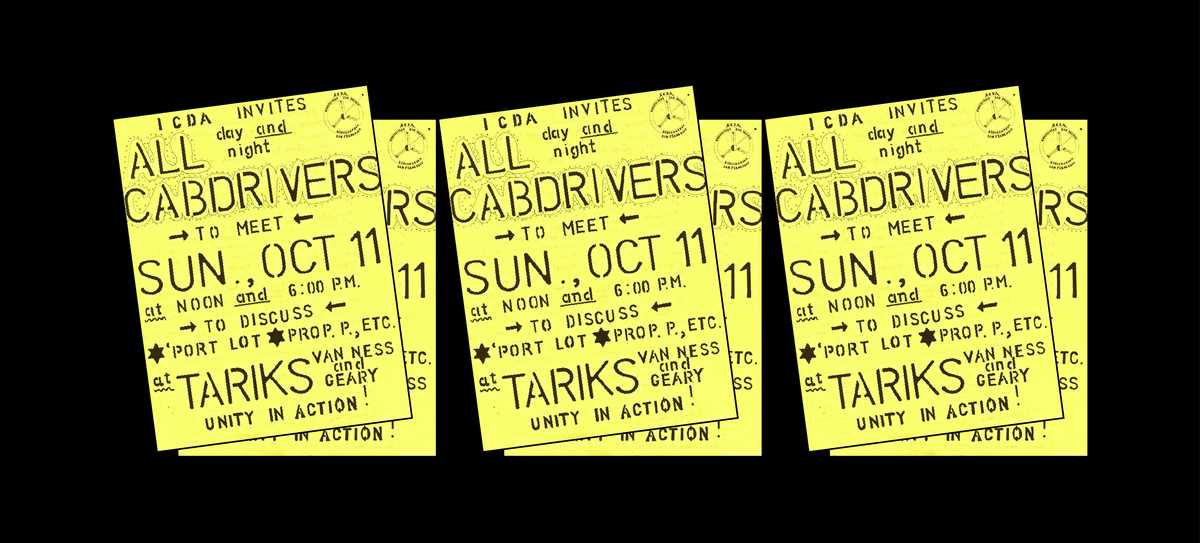

The existing structures of labour and technology may have underpinned the gig-work model, but its proliferation into the mainstream was augmented by a playbook of blatantly aggressive strategies adopted by apps like Uber and Lyft — including bulldozing over existing labour laws, lobbying, and funding political campaigns. A particularly early example of the latter is the 2011 campaign of Ed Lee, then the mayor of San Francisco, who, in his term, was instrumental in creating a conducive regulatory environment for platform apps in the city.13 In 2012, Lee and the San Francisco Board of Supervisors (the legislative body of the city and county) launched the ‘Sharing Economy Working Group’, aimed at ‘modernizing’ city laws to accommodate businesses like AirBnB, as well as ride-hailing apps, whose operations clashed with existing regulations that focused on safety standards, business licenses for hotels, and zoning restrictions for residential areas. The efforts of regulatory bodies like the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) were impeded by Lee, preventing them from claiming jurisdiction over these platforms. Instead, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) was encouraged to claim jurisdiction, bypassing local authorities. In 2013, the CPUC announced their decision to create a new regulatory category, which would become the bedrock of the platform economy’s model of deregulation — the Transportation Network Company (TNC).14

Regulatory Hacking and the ‘Independent Contractor’ Classification

“We’re just fcking illegal” - Nairi Hourdajian, former Director of Global Communications at Uber, in a message to colleagues in 2014 (Uber Files, 2022)*

Between its launch in 2009 and the pinnacle of its expansion in 2017, Uber was running its services in over 80 countries across the globe.15 Unlike the precursors to Uber’s model, which were hitherto functioning at a relatively small scale, the latter’s rapid expansion relied on violating labour laws and exploiting the gaps between existing regulatory frameworks and new technology. These gaps were transformed into the premises of Uber’s booming empire, using the tactical blueprint now well-known as the ‘Uber playbook’.

At the outset, Uber begins by launching operations in a particular location by overlooking any regulations in place, including price controls, driver licensing and registration, insurance policies, safety measures and consumer protections.16 This forces local governments or public officials to respond by either banning Uber or by allowing it to continue operations, as opposed to actively integrating the platform into the existing regulatory frameworks. The government’s response, usually transpiring after Uber has already built a labour and consumer base through incentives, is then met with extensive lobbying efforts to amend regulations to suit the platform’s operations. The existing carve-outs in US labour laws served merely as a prototype for a tactic that is now known as ‘regulatory hacking’.

Between 2014 and 2017, Uber and Lyft worked with venture capitalist and political strategist Bradley Tusk to lead efforts to pass a new set of carve-outs that would exempt Transportation Network Companies or TNCs (from the CPUC’s 2013 legislation to integrate renewable energy, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions) from following state-ordained labour regulations as employers by designating drivers as contractors instead of employees. By the end of 2017, over 40 states in the US had enacted the TNC carve-out laws. Tusk, who was previously a campaign manager for Michael Bloomberg’s 2009 mayoral campaign, also led the scaling-up of TNC carve-outs by lobbying for a wider ‘marketplace contractor’ policy, first passed in Arizona in 2016.17

The financial value extracted by Uber and Lyft from the drivers’ labour through the independent contractor classification could perhaps be inferred through the figures from a 2015 class-action lawsuit filed by 385,000 drivers from California and Massachusetts alone. The lawsuit claimed that, had the drivers been classified as employees, they would have been entitled to expense and maintenance reimbursements worth $730 million. The plaintiffs also filed for damages of an estimated $122 million in tips, making a total of $852 million in potential damages.18 In the settlement, Uber agreed to a total sum of $84 million, and an additional $16 million should the company go public. The drivers remained independent contractors.19

Uber’s deregulation strategy was not limited to the US. Between 2013 and 2017, Uber operated illegally in countries including the Czech Republic, Germany, Spain, South Africa, Sweden, Turkey and Russia. Attempts by regulatory agencies or law enforcement were met with Uber’s ‘kill switch’ protocol, which would restrict access to sensitive data on office computers. The 2022 Uber Files leak revealed that this protocol was used at least a dozen times, in Belgium, France, India, Hungary, the Netherlands and Romania.20

Along with Uber’s globally-reaching operations, often with a murky legal status, clandestine political alliances across the world facilitated the breakdown of existing labour laws. In France, Uber launched the illegal UberPop service in 2014, which allowed unlicensed drivers to offer rides at discounted rates. Despite being promptly banned by the government, UberPop continued running for months until it suspended operations in June 2015, at a time when taxi drivers’ protests in the country had reached a volatile point.

The 2022 Uber Files leak revealed that Emmanuel Macron, then the Minister of Economy, Industry and Digital Affairs, had negotiated a deal with the company to terminate its UberPop service, in exchange for the government relaxing regulations on chauffeur-driven car (VTC) licenses. In a text exchange that has since been leaked, Kalanick asked Macron if they could trust Bernard Cazeneuve — then the Minister of the Interior, who ordered the official termination of UberPop in June 2015. Macron responded, saying that Cazeneuve had accepted the ‘deal’, and that meetings had been scheduled to rewrite the regulatory frameworks. By February 2016, Macron had signed a decree that would reduce the mandatory training hours for VTC drivers from 250 to 7.21

Mark MacGann, formerly Uber’s chief lobbyist, who turned whistleblower by leaking the Uber Files, describes the playbook as including “...closed door meetings with officials, hiring their former advisors, and running campaigns to appear as champions of economic opportunity — all while avoiding the topic of our labour model.” Records reveal over a hundred meetings between Uber executives and public officials between 2014 and 2016, twelve of which were undisclosed meetings with representatives of the European Commission.22 This includes undisclosed meetings with at least six Conservative MPs from the UK — George Osborne (then the chancellor), Matt Hancock, Michael Gove, Priti Patel, Sajid Javid and Ed Vaizey.

In August 2014, Osborne attended a dinner in California hosted by Rachel Whetstone (then a Google executive and Uber investor, and reportedly a close friend of David Cameron, then the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom), which included Kalanick and Larry Page (co-founder of Google). The event was held just months before Osborne announced the ‘Google Tax’.23 Purportedly aimed at multinational companies that were avoiding UK corporation taxes by shifting their profits outside the country, the tax was found to be inefficient, with revenues slumping to zero in 2021.24 Uber’s brazen lobbying in the UK eventually resulted in Boris Johnson (then the mayor of London) and Transport for London (a regulatory body for public transport in the city) dropping proposed regulations including a compulsory five-minute wait time for services, a requirement for operators to allow pre-bookings up to seven days, and a ban on showing available cabs on a map.25 In an exchange with Kalanick in September 2014, Whetstone wrote, “As you know, George [Osborne], that is most of the problem solved from the government side”.26

Apart from alliances with representatives in office, Uber also built upon its political network by hiring former officials. In 2016, Uber hired Gesner Oliveira — former president of the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (CADE), Brazil’s national antitrust agency (between 1996-2000) — on their Public Policy Advisory Board. In March 2018, following heavy lobbying and a visit from Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, the Brazilian Congress approved a watered-down version of a regulatory bill that was proposed in the previous year. The clauses removed from the original bill included requirements for special taxi license plates and additional car insurance.27 Around the same time, CADE published a working paper arguing for the gradual deregulation of taxi services.28

In the Global South, Uber’s deregulation strategy was accentuated with localisation tactics, policy laundering, and ruthless incentivisation. Already operating in ten cities in India by 2014, Uber faced a controversy-fuelled ban in Delhi as a result of the state’s response to a sexual assault case involving a driver, as well as other regulatory roadblocks in other states like Maharashtra and Karnataka.29

Not only did Uber resume services in Delhi while still being banned, but they also announced a billion-dollar investment in their Indian operations, partnering with the digital arm of the Times of India, the largest media conglomerate in the country.30 An analysis of the Times Group’s coverage between 2015 and 2022 reveals that while their newspapers reported on crimes committed by Uber drivers, the company’s policies and investments were largely covered in a positive light.31 By 2016, labour regulations in India were amended to allow drivers and other platform workers to be classified as ‘partners’ instead of employees.

In South Africa, Uber launched with offers of cash incentives of around $400 for drivers to sign up with the platform, in addition to cash subsidies per trip. Over time, the number of drivers on the platform multiplied, the subsidies and incentives were cut, and driver commissions were slashed. The Uber Files reveal that this strategy was recommended by top executives to local managers around the world, with emails that refer to drivers as a mass of “supply”.32

When Uber launched in South Africa in 2013, the country’s unemployment rate was 24.6%, which Uber used to its advantage by weaving a narrative of entrepreneurship and mobility for the drivers, making them dependent on the model and leveraging that dependence. In a 2014 submission to the South African government, Uber stated that the platform “not only creates more jobs for more people, it creates better-paying jobs”. By 2015, the country’s unemployment rate had increased to 25.1%.33 By the end of the year, Uber had cut back on most driver incentives and subsidies and decided to increase the platform’s commission from 20% to 25%. Within fourteen months of its launch in Johannesburg, Uber had already become profitable, turning South Africa into one of its key markets.34

The company also knowingly implemented policies that would put drivers at risk of harm. After initially rejecting cash payments in the country by acknowledging them as less safe for drivers, Uber enabled cash payments, which, in turn, required drivers to keep cash in their cars, making them targets for potentially violent robberies. Catering to a large section of customers who did not use card payments, the policy was rolled out with the hopes of boosting rides by as much as 30%. The Washington Post reported multiple accounts of drivers who had been beaten up or hospitalised due to injuries from these robberies.35 A 2018 labour lawsuit by a group of unions and drivers against Uber states that there is no driver discretion to refuse to drive in an unsafe area. Instead, cancellations or acceptance rates were used to deactivate drivers from the app.36 In MacGann’s words, at the 2022 Web Summit in Lisbon, “We knew we were breaking laws…we were actually breaking democracy itself”.37

The Platformisation of Labour in the Global South

“Violence guarantees success” - Travis Kalanick, founder and former CEO of Uber, in a message to company management in 2016 (Uber Files, 2022)

The swift expropriation of the global labour market by the platform economy is tied to the easy assimilation of the model in the context of developing economies in the Global South. By 2018, a slew of platforms, including Grab (Southeast Asia-based ride-hailing and food delivery app launched in 2012), Gojek (Indonesian multi-services platform with presence across Southeast Asia, launched as an app in 2015), Rappi (Latin American ‘super-app’ that includes services like food delivery and payment processing, launched in 2015), and Glovo (2014-launched delivery app headquartered in Spain) were operating across the world, replicating Uber's labour model and expansion strategies.

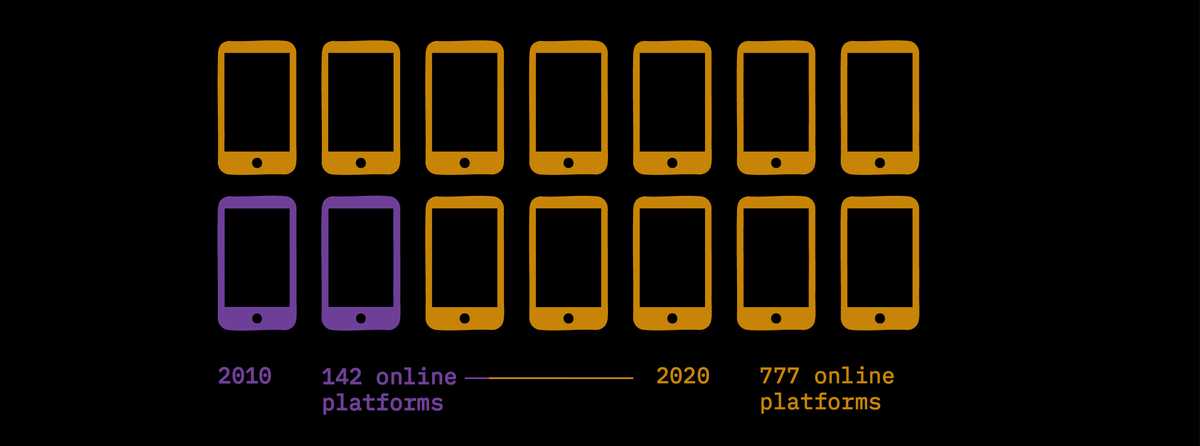

The number of online platforms rose from 142 in 2010 to at least 777 in 2020.38 In 2023, the World Bank estimated that the gig economy accounted for around 12% of the global labour market.39 These platform apps gain market dominance particularly rapidly in developing economies in the Global South with weak regulations and labour protection frameworks.

The higher unemployment rates in these countries provide a ready, precarious workforce, while deeply entrenched socio-economic inequalities ensure a willing consumer base. By the time regulatory forces catch up, many of these platforms have already established a stubborn presence in the market, ensuring that any efforts to enforce regulations become a formidable challenge. In March 2022, the Tanzanian government capped ride-sharing app commissions to 15%, upon which Uber suspended operations with a one-day notice, and Bolt (a 2013-launched ride-hailing app headquartered in Estonia, and a significant competitor to Uber in Europe) scaled back operations significantly. By September, both platforms resumed services after reaching an agreement with the government, and by December, the apps were authorised to charge a 25% commission and a 3% booking fee.40

The cheap, mass ‘supply’ of labour in the Global South also allows these companies to extract higher value out of workers. They do this by presenting them with extremely low pay rates as compared to their Western counterparts, fluctuating compensation rates, and introducing platform fees. Fairwork Kenya’s 2021 report stated that Glovo was the only platform that provided sufficient evidence that their wages for couriers did not fall below the statutory minimum wage (unlike Uber, Bolt, UberEats, etc.).41

In 2020, the rate of unemployment in Kenya was 5.6%.42 However, in young people aged 15-24 years old — who accounted for 20% of the Kenyan population, and formed a majority of the platform labour force — the unemployment rate was estimated between 16.6-17.4%.43 In 2020, an estimated 2 million drivers in Indonesia worked for Grab, the largest platform app in Southeast Asia. In 2018, their average daily gross income was $29.74. After the platform stopped financial incentives in February 2020, the figure decreased to $17.77. By April, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it had dropped even further to a mere $5.54.44 In Brazil, Rappi implemented a $2.4 weekly fee in January 2024 for delivery workers to use the platform.45

The independent contractor or partner classification also disproportionately affects workers in countries with a large surplus labour force by creating a captive workforce that is dependent on the platform model for their livelihoods, affecting chances of upward socio-economic mobility for the working classes. In India, Uber and Ola (an India-based ride-hailing app) account for 1.5 million and 1.2 million drivers, respectively, while food delivery apps like Swiggy and Zomato together account for half a million delivery workers. In contrast, India’s largest conglomerate, the Tata Group, accounted for a total of 729,000 employed workers in 2019.46

The lack of employment rights means that platform apps have no obligation to provide health insurance or even rudimentary health and safety measures for the workers. A 2023 study found that food delivery workers in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, were breathing extremely polluted air with high concentrations of particulate matter and volatile compounds, including benzene, a known carcinogen.47 While these findings are certainly a reflection of the general quality of air in the city (Ghaziabad reported an AQI of 173 in 2022), it must be noted that outdoor workers are particularly vulnerable to air pollution, and the number of outdoor workers in India increased by 49.4% between July 2018 and June 2019.48 As recently as April 2025, 150 workers in Varanasi were barred from their login IDs on BlinkIt, a Zomato-owned platform that promises hyper-quick deliveries in under ten minutes. The workers had demanded cotton uniforms instead of polyester ones, shaded waiting areas with drinking water, and an end to mandatory work in the afternoons between 12 and 4 PM when the summer sun is at its peak.49 On the first day of the strike, the maximum daytime temperature in the city was 43 degrees Celsius.

The extreme levels of socio-economic inequality in countries like India, particularly along the lines of the urban-rural divide, indicate that a significant section of the gig-workforce (concentrated largely in the urban centers) is migrant workers. Between the first and second halves of the 2018-19 financial year alone, Delhi saw an 88% increase in migrants in the gig workforce.50 Moving to urban centres in search of employment, these workers are extremely economically vulnerable, with pressing financial constraints like rent, debt and sending money back home — making them easy targets for particularly exploitative and inhumane treatment at the hands of platform companies.

In 2024, Zepto, an India-based quick-commerce delivery platform, announced a Rural Mobilisation Program (RMP), claiming to “bridge the gap between urban and rural areas by offering employment prospects in Tier 1 cities where Zepto operates”. Advertisements for the program, many of which were reportedly paid videos by YouTubers, made claims of a monthly salary of ₹30,000 (~$350), with benefits like free food and accommodation for 42 days. In May 2025, the Delhi-based Rajdhani App Workers Union (RAWU) lodged a complaint with the Labour Department against Zepto and its third-party vendor, M/S Kilton Geo Engineering Pvt. Ltd. The complaint describes the RMP as a system of ‘digital bonded labour’ and alleges that the workers hired under the Program — largely youth from rural areas in Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh — were misled about the terms of their employment, and were met with inhumane working conditions. The union claims that the workers were not only misled about having to bear the costs of the gig themselves, but were also subjected to illegal practices, including the vendor withholding joining bonuses and arbitrarily deducting weekly payments. The complaint also states that the promised accommodation was 10-12 workers crammed into a small room, and the ‘free food’ was not only stale and unfit for consumption, but also contingent on the workers completing 100 orders per week.51

The gamification tactics used by platform apps across the globe to incentivise workers to take on more gigs, work longer hours or stay registered on the platform also take on more unscrupulous forms in the Global South. Gamification, the use of game elements like points, leaderboards, challenges and rewards in non-game contexts, is not a particularly new strategy used by employers to manipulate productivity. Platform apps, however, use algorithms informed by a mass of data, including worker profiles, driving patterns, consumer demand and locational information, to deliver individualised prompts to the workers. This may look like an arbitrary challenge presented to a worker when they log into the app, stating that the completion of a certain number of gigs in a specified time period would earn the worker a particular sum as a bonus.52

In Indonesia, Gojek uses an infamously opaque system that results in an algorithmic disparity in gig allocations and incomes. A mathematical simulation conducted by researchers at the University of Zurich found that, with an increase in the number of workers on the app, the algorithm widens the income inequality between drivers, irrespective of similar qualifications and working hours.53 In India, Swiggy uses its dynamic rating system to determine the kind of health insurance a worker is eligible to receive. The highest-ranked workers (Gold-rated) are provided health insurance for themselves and their families, the Silver-rated workers receive insurance, but their families are not eligible, and the Bronze-rated workers are only covered in case of accidents.54

Marketed as a creator of opportunities and livelihoods in developing countries with high unemployment rates and a large, predisposed workforce, the platform economy promptly latches on to these markets with a firm grip. The gig-work model’s promises of empowerment portend an extreme precarisation of this workforce, with the ability to undermine global institutional pushback derived largely on the scale of the value extracted from their labour.

Lobbying Networks and Funders with Deep Pockets

“It’s about working hand in hand…” - Anthony Tan, CEO of Grab, in a 2018 interview with CNBC

The groundwork of Uber’s rapid deregulation strategy is reinforced by a web of big-money backers, lobbying platforms, international think tanks and academic collaborators. In 2011, Uber received $32 million in funding led by Jeff Bezos, Menlo Ventures and Goldman Sachs. In 2013, Google followed with a hefty investment of $258 million.55 Major funders for platform app companies include VC firms like Andreessen Horowitz, Benchmark Capital and Greylock Partners.

Japanese investment group SoftBank, which launched its ‘Vision Fund’ in 2016 with a sum of $93 billion to invest, is now one of the largest funders for platform app companies globally. Founded in 1981 by then-software distributor and now-investor Masayoshi Son, SoftBank funds Uber in the US, Ola and Swiggy in India, DiDi in China, Grab in Southeast Asia, and Rappi in Latin America.56 The scale of SoftBank’s stakes allows them to build and control regional monopolies, like in Southeast Asia, where Uber sold its operations in 2018 to Grab. SoftBank, however, funds both companies.57

The inordinate scale of capital invested in platform startups is reflected, in part, in lobbying strategies. A leaked document from the Uber files suggested that Uber’s global lobbying budget for 2016 was a staggering $90 million. In 2020, the company spent $2.3 million on lobbying in the United States alone, more than what major oil companies or defence contractors spent that year. In 2024, Uber disclosed lobbying expenditure in the States was over $2.6 million, with 27 of its 37 lobbyists classified as Revolving Door Personnel — those who move between public-sector roles as legislators or regulators and lobbyists for industries in the private sector. 58

Conventions like the World Economic Forum in Davos, the Web Summit in Lisbon, and the New Economy Forum in Singapore became locations where platform entrepreneurs could access high-ranking government officials directly, outside public scrutiny. In 2016, Joe Biden, then the US Vice President, met with Kalanick at Davos before tweaking his keynote speech to feature Uber’s impact.59 In Davos, Uber executives also met face-to-face with Macron, Enda Kenny, then the Irish Taoiseach/Prime Minister, and Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli Prime Minister.60

A network of affiliated think tanks and paid academic research outputs provided legitimacy to the platform labour model to aid lobbying and deregulation processes. The Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), a libertarian think tank, publishes annual agendas for the United States Congress that are aimed at influencing policymakers to, in their words, ‘reform America’s unaccountable regulatory state’. In their 2016 Agenda for the 115th Congress, the CEI argued against the US Department of Labour’s worker classification policies — which resulted in a recovery of over $74 million in back-wages in the 2015 Financial Year — and recommended legislation that would enable those who ‘prefer the flexibility’ of the contractor status, instead of being ‘forced into an employment relationship’.61

The CEI states that their experts meet with officials, including members of Congress, state legislators and legislative staff, and that they actively participate in the country’s regulatory process by testifying at congressional and agency hearings and meetings. Articles — by current and former members of the CEI, like Iain Murray and Trey Kovacs — that promote the Uber model, and argue against regulatory legislation like California’s 2019 Assembly Bill 5 (AB5), are regularly published by mainstream media as well as by other conservative think tanks such as the Foundation for Economic Education. In 2018, Kovacs also provided Congressional testimony against unionising on official time.62

A significant number of media platforms that published anti-AB5 articles, like the Daily News of Los Angeles and the Daily Breeze, were found to be owned by the same media conglomerate — Digital First Media, whose own workforce largely comprises independent contractors and freelance writers.63

In 2018, Uber partnered with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank Group to publish a report about how the deregulation model pioneers women’s mobility and empowerment by providing women drivers with flexibility. The report cites other papers linked to Uber’s lobbying, leaving much room for questions as to how many of its claims are based on independent research. The IFC has, in the past, also framed mining and insurance as sectors that push for women’s empowerment, particularly in the Global South.64

Uber’s lobbying strategies also relied on hiring high-profile academics and professors to publish research that would validate the model. One of the earliest deals of this kind, in 2015, was signed with the now-deceased Alan Krueger at Princeton University. The Uber files revealed that he was paid nearly $100,000 for a study that hailed Uber as a creator of good jobs, and was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).65 The paper was also published with a disclaimer that Krueger worked as a consultant for Uber between December 2014 and January 2015, and that the co-author, Jonathan Hall, was ‘an employee and shareholder of Uber Technologies before, during, and after the writing of this paper’.66 An analysis of this paper found that its research methods included “sample bias, leading questions, selective reporting of findings, and an overestimation of driver earnings”.67

In 2016, Uber agreed to a €100,000-arrangement with Prof. Augustin Landier of the Toulouse School of Economics to produce a report which could be ‘actionable for direct PR to prove Uber’s positive economic role’. In Germany, Prof Justus Haucap at Düsseldorf University’s Institute for Competition Economics (DICE) agreed to collaborate with the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) to produce a study on ‘consumer benefits from a liberalisation of the German taxi market’, for a fee of €48,000.68

That the unscrupulous lobbying tactics used by Uber are public knowledge can be credited primarily to the Uber Files leak in 2022. However, the lack of systemic transparency suggests that many such transactions continue to take place behind closed doors.

Dissolving the Picket Line

“Communication is important” - David Plouffe, former chief advisor at Uber, in 2016 to the New York Times

The platform model has been met with considerable pushback, not only from regulatory bodies or governments, but also from workers' collectives and unions. Uber and other companies have not only lobbied for anti-union policies, but also continue to use their lobbying networks to discourage unionising, hampering collective-action strategies and practices.

On 10th May 2016 — a day after the details of the 2015 class action lawsuit against Uber and its $852 million claim were released — David Plouffe, then Uber’s chief advisor and board member (and previously campaign manager for Barack Obama), launched an Independent Drivers Guild in New York, working alongside the International Association of Machinists.69 The guild promised protection and support to Uber drivers in the city and aimed to address their complaints. However, no concerns on employment status, benefits or fare negotiations were addressed. The drivers were also prohibited from collective bargaining, and would not be able to reach out to the National Labour Relations Board.70

In 2015, Seattle passed a law allowing ride-sharing app drivers to unionise. This led to the US Chamber of Commerce filing a suit against the city over the law in 2016, supported by Uber and Lyft.71 Uber’s response to the law included initiatives where Seattle-based drivers were contacted by the company’s representatives with anti-union messaging, seemingly in the guise of a driver satisfaction survey. Uber also hired Ergo, a CIA-linked intelligence firm, to investigate union politics in the city, describing the efforts as research on the city’s political landscape.72 Uber had also hired Ergo to investigate the plaintiffs and the lawyer of a class action lawsuit filed against them, in the context of the app’s surge pricing policy violating antitrust laws.73 Plouffe is part of Ergo’s Senior Advisors Team, which comprises former CIA officials, military advisors and political representatives, including Amos Yadlin (Chief of the Israeli Defense Forces Military Intelligence Directorate, 2006-10) and Ted Singer (CIA Chief of Station in the Middle East.

The US Chamber of Commerce’s lawsuit against the 2015 Seattle ruling was also supported by the Freedom Foundation.74 Known for its aggressive anti-union campaigning tactics against both public and private sector unions in the States, the Foundation runs ‘opt-out’ campaigns intimidating union members to stop paying dues, supports anti-worker legislation and runs ‘alternative’ employee organisations, a recent one being the Teacher Freedom Alliance. In a speech to libertarian think tank Americans for Prosperity in January 2016, Anne Marie Gurney (then the Oregon coordinator for the Foundation) said, “Our number one stated focus is to defund the political left.”75 The Foundation is affiliated with the State Policy Network (SPN), a group of right-wing think tanks across the United States. In 2017, the SPN led a nationwide campaign to “defund and defang” public sector unions in order to deprive progressive politicians of a significant source of funding and support.76

Partners of the SPN include the previously mentioned Competitive Enterprise Institute and the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), an ultraconservative lobbying group whose participants included Uber and Lyft. In 2014, the two platforms publicly distanced themselves from ALEC. However, a 2018 study published by the National Law Employment Project found continuing links between the TNC industry and ALEC. In 2014, model TNC legislations were circulated by ALEC, of which elements and even specific wording have made their way into state laws.77 The State Policy Network, the Freedom Foundation, Americans for Prosperity, the Competitive Enterprise Institute and the American Legislative Exchange Council are all part of a list of organisations funded partly by, or related to, the Koch Foundation.78

In the US, DoorDash, Grubhub, HopSkipDrive, Instacart, Lyft, Shipt, and Uber are members of Flex, a lobbying group for platform apps. Behind a smokescreen of policy initiatives that include promoting environmental sustainability and nurturing Black communities, Flex aims to defend the platform business model from regulations that would defend workers’ rights, including the right to unionise and strike.79 Flex CEO Kristin Sharp’s career consists of a range of roles in technology, innovation, and national security policy in the U.S. Senate — including being the Deputy Chief of Staff to Senator Mark Warner, Legislative Director for Mark Pryor and Amy Klobuchar, Advisor to Richard Lugar on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and senior staff roles on the Senate Homeland Security.80

In 2022, in the UK, Deliveroo signed a partnership agreement with the GMB, the largest trade union in the country, where the latter would work on safety, security, diversity and wellbeing, while reinforcing that the riders are self-employed — much like the New York Guild, which promised support and benefits while also diluting the workers’ rights to collectivise.81 At the time of signing the agreement, Deliveroo was embroiled in a six-year-long series of legal battles against a much smaller union, the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB). In 2023, the UK Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the riders are self-employed and do not have the right to collective bargaining.82 A 2024 article found that apart from two Joint Partnership Council meetings held between GMB and Deliveroo, there were no significant updates on the partnership’s efforts. The GBM’s absence was noted not only from the large, much-publicised Valentine’s Day strike of the same year (which was organised by the grassroots group Delivery Job UK) but also in media coverage related to the strike.83 Since 2024, the GMB’s Deliveroo Noticeboard has posted more frequent updates on pay negotiations, restaurant waiting time and more recently, a shareholders' offer by DoorDash. However, apart from a proposal for a riders’ bonus on Valentine’s Day in 2025 — the outcome of which is unclear — there was no mention of any strike or protest held in the last year, nor was there any response to openDemocracy’s findings that Deliveroo had encouraged partner restaurants to call the police on protesting riders in February 2024.84

In India, Swiggy’s food delivery workers protested pay cuts in August 2022 by organising a strike. Swiggy responded by mandating two shifts during the strike dates and threatening those who didn’t fulfill the condition with a suspension of their IDs. Many workers left organising channels, and the strike was called off in two days.85 There have also been reports of Swiggy having sent agents to collect information and having scanned Facebook accounts to target protesting drivers.86 Employers using underhanded tactics to break workers’ strikes is not a recent phenomenon by any means, but the nefarious methods used by platform companies to institutionalise union-busting target the very foundation of labour rights that workers have fought for centuries to establish. The web of players and funders across the world working to undermine forms of collective action and unionising also indicates that they continue to be seen as a significant threat to the platform model, even if it is an uphill struggle for workers.

Alliances for a Shared Goal

“Competition is for losers” - Peter Thiel, co-founder of PayPal, Palantir Technologies and Founders Fund (with investments in Lyft and Postmates), in a 2014 op-ed for the Wall Street Journal

The strategies used by platform startups, the scale of funding and common investment, and the steady focus on consistent lobbying point to the fact that what these companies are selling is not a range of services, but a deregulated, destabilised labour model at the global level. To this end, companies merge or pull out of markets, allowing their competitors to form a monopoly and strengthen their positions. Uber and Lyft, while providing the same service, have been collaborators in lobbying efforts since the early years of their inception.

In 2014, European food-delivery platform JustEat fuelled its Latin America expansion by investing heavily in Brazil-based iFood, acquiring a 33.3% stake in the company, with the rest owned by Prosus (a Dutch multinational investment group) and its Brazilian affiliate, Movile. By 2021, iFood dominated over 80% of Brazil’s food delivery market.87 In 2022, JustEat sold its stake in iFood back to Prosus and Movile for $1.8 billion, in order to bolster profits.88 In February 2025, Prosus acquired JustEat for $4.6 billion (€4.1 bn). The deal made Prosus the fourth-largest delivery group globally, with the company owning 28% of Delivery Hero (Germany-headquartered food delivery company with a presence in over 70 countries), 4% of Meituan (Chinese food delivery company), and 25% of Swiggy.89 Owned by South African tech company Naspers, Prosus announced a public offer to all of JustEast’s shareholders to purchase their shares for an all-cash offer at €20.30 per share.90

Prosus also declared that its use of Artificial Intelligence ‘revolutionised operations’ at iFood in Brazil.91 It must also be noted that according to iFood’s own statistics, 25% of its drivers in the country are sub-contracted through companies like CR Express, and are facing even more precarious working conditions — a reflection of iFood’s near monopoly in the country.92

In 2020, Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart and Postmates spent over $200 million on lobbying for California’s Proposition 22.93 The ballot initiative was led by the platform apps to exempt app-based transportation and delivery companies from the state’s 2019 Assembly Bill 5, which required companies to classify gig workers as employees. Passed by a 59% majority, the bill became a law by November 2020, requiring a 7/8 majority to amend or overturn it. Challenged by lawmakers and ruled unconstitutional in 2021, the law was, nevertheless, upheld in 2023 and by the California Supreme Court in 2024.

The deregulation mission of the platform app consortium is not restricted to tech startups either, with more traditional employers now adopting similar lobbying strategies, eroding existing labour laws and regulations. In 2019, the Coalition of Workforce Innovation was formed, which includes platform apps like Uber and Lyft, as well as major tech companies (including Google, Meta, Apple, Microsoft), retail giants (including Walmart, Amazon), MLMs and staffing agencies. In 2023, Apple and Foxconn lobbied to change labour laws in Karnataka, India — proposing an increase of daily working hours from 9 to 12, effectively prescribing a 48-hour work week.94

Growth, not profit, is the ethos of this structure. Subsequently, this also ensures a steady, global supply of labour that is entirely dependent on a few companies for their livelihoods, chipping away at their collective bargaining power, and pushing a larger workforce than ever into further precarity.

Is the Gig up?

Over the last few years, concerted efforts by trade unions, workers' collectives and policymakers have helped strengthen labour regulations to withstand the platform model, particularly in Europe and Latin America. Spain’s 2021 ‘Rider’s Law’ added provisions to the Workers’ Statute that confirmed employee status for app-based workers, granting them access to labour rights such as fixed hourly pay, sick pay and holiday pay. In 2022, the government charged Glovo with a fine of €79 million (nearly 15 per cent of Glovo’s annual expenditure) for breaching employee classification in Barcelona and Valencia between 2018 and 2021.95

Belgium (2022) and Portugal (2023) are among the countries to have amended their labour codes to introduce a legal presumption of employment status for workers. In 2023, Peru’s Commission of Labour and Social Security approved a bill that categorises employment status based on the level of subordination and the number of working hours per day and week. Greece and Malta have introduced similar laws defining criteria for employment status or legal presumption. Mauritius and Ecuador included the definition of ‘platform worker’ in existing employment categories. Argentina, Chile, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Peru, and Uruguay have mandated specific provisions in contracts for gig workers.96

In 2024, the Council of the European Union announced the Platform Work Directive, which requires companies to notify workers about the use of AI and how it will affect working conditions including work allocation and performance monitoring, and prohibits the use of AI tools to collect workers’ personal data during non-work times, private conversations (including those with other workers or representatives), or process biometric data to establish identity. The directive’s provisions for worker misclassification, however, are slightly less straightforward. Instead of prescribing rules for worker misclassification, it introduces a rebuttable legal presumption, according to which workers contracted after the law comes into effect would be presumed to be under employment, unless the platform proves contractual status.97

In many developing economies in the global South, however, the existing frameworks of labour regulations were developed alongside rapid industrialisation and globalisation, aimed at ‘catching up’ with developed countries of the global North, fostering the development of a massive sector of informal and unorganised labour in the modern sense. Characterised by weak welfare measures and protections for workers, dire working conditions and extreme precarity, these countries form a strong foundation for the expansion of the platform economy. In Brazil, the number of delivery app workers rose by 979.8% between 2016 and 2021, with a current estimate of 1.4 million gig workers.98 In India, the platform sector was estimated to have nearly 8 million workers in 2020, which is estimated to nearly triple to 23 million by 2030.99 The neoliberal ‘catch-up’ development policies and weak regulatory landscapes that facilitated the growth of the platform economy at the expense of their larger workforce ensure that these countries have a much longer and more complex struggle ahead.

This is not to say there has been no significant pushback and legislative efforts in these countries. In 2023, the state of Rajasthan in India passed the Rajasthan Platform-Based Gig Workers (Registration and Welfare) Act, becoming the first Indian state to regulate platform-based work. The Act made provisions to register gig workers under a separate category of work and introduced social security and a welfare fund for the workers.100 In May-June 2025, the states of Karnataka and Telangana also followed suit. The law passed by Karnataka not only provides social security, but also added provisions for algorithmic transparency, protection against blocking workers’ IDs and fair terms of contract. The Telangana Gig and Platform Workers (Registration, Social Security and Welfare) Bill, 2025 takes these provisions further by ensuring grievance redressal and fair wages. These regulations have been a long time in the making, and follow the relentless struggles of workers’ unions and political organisations like the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (TGPWU) and Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS).101

In Brazil, a wave of mobilisation in 2020 gave rise to platform cooperatives that subverted the model to create apps and services that were owned and managed by the workers themselves. These include Liga Coop (a ride-hailing service with 2700 members) and Señoritas Courier (a courier service by cis women and trans people). The Homeless Workers’ Movement (MTST) also created a chatbot to connect people looking for a range of services to people who can provide them, called Hire Those Who Struggle.102

In spite of the larger global shift toward strengthening labour laws, the platform economy’s deregulation model continues efforts to adapt to legislation and decimate workers’ rights. Platform app coalitions like the CWI have been supporting a ‘third way’ carve-out for independent workers in the United States, which would classify gig workers as a separate category of workers, allowing the companies to continue dismantling the foundation of labour rights while acceding to a bare minimum in terms of worker protection. The CWI has also been lobbying for the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act in the States, which broadens access to collective bargaining and organising protections in the country, spending $67.6 million on these efforts between 2019 and 2022.103

Industries with traditional employment structures are also moving to the platform model, most significantly in the case of the healthcare sector. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, in the States, ‘on-demand nursing’ platforms such as CareRev, Clipboard Health, ShiftKey, and ShiftMed have adopted the Uber playbook and expanded into the sector with the same pitfalls, and the same promise of flexibility.104 The implications of this level of proliferation, while difficult to anticipate in entirety, need to be addressed promptly.

Under the pretext of flexibility and entrepreneurship, the global web of the platform economy and its deregulation model cements precarity as an essential feature of labour across types and sectors of employment, decimating the framework of labour protections — imperfect as it may be — woven over decades of relentless struggle by workers and activists. Meanwhile, despite questions of long-term profitability, the platform economy continues not only to adapt to changing regulatory environments, but to thrive on the backs of the workers it overlooks. In April 2025, a month after Urban Company launched its InstaMaids service in India, the app filed a draft proposal for an IPO valued at ₹1,900 crore (~$223 million).105 In June 2025, the company reported a net profit of ₹240 crore (over $28 million). The company’s 2023 report stated that their ‘service partners’ earned a monthly average of ₹33,469 ($390).106 To borrow the words of Thibauld Simphal, Uber’s Global Head of Sustainability (although originally used while deploying Uber’s ‘kill-switch’ protocol to escape legal ramifications), “The most difficult part is continuing to act surprised”.