The (Un)Holy Alliance

In May 2024, Argentina’s courts ordered President Javier Milei to release five tons of food aid that had been left to rot in storage. "In the face of this group of people who suffer from pressing food insecurity and on whom the cost of the paralysis denounced weighs heavily, there is an urgent need to take positive action," the courts ruled.1

As a part of Milei’s attempts to “reform government, he had given 177 a million pesos (roughly 9 million USD) contract to the evangelical Christian Alliance of Evangelical Churches of Argentina (ACIERA) to oversee food distribution.2 This was done to curb public spending, diverting funds from the soup kitchens that had previously provided the service. However, by March 2024 hunger lines were forming outside the office of Human Capital Minister Sandra Pettovello,3 as poverty rates exceeded 50 percent4 and ACIERA proved unable to address the mounting humanitarian crisis.

But ACIERA is not a marginal organization incapable of fulfilling an administrative function. It is instead a key political actor within Milei’s government. Nadia Márquez — the daughter of Hugo Márquez, a pastor and ACIERA’s vice president — was appointed deputy to the far-right La Libertad Avanza party by Vice President Victoria Villarruel, herself a traditionalist Catholic with ties to the Priestly Society of Saint Pius X.

The alliance between Milei and ACIERA, an organization in the Charismatic Christian tradition, exemplifies a growing trend across the globe. From Argentina to Brazil and beyond, Pentecostalist Christians and those influenced by their practices are becoming a vital pillar of contemporary right-wing movements. It provides not only grassroots energy but also theological legitimacy. As the Reactionary International advances its agenda, it is increasingly the Charismatics who provide its spiritual muscle.

The Origins of Charismatic Christianity

Milei’s evangelical allies — including Nadia Márquez and the leadership of ACIERA — are part of a rapidly expanding Christian movement often called Charismatic Christianity. Sometimes referred to as “renewalists,” what distinguishes Charismatic Christians from most other Christians is their belief in supernatural “spiritual gifts”— such as prophecy, healing, and speaking in tongues, which they claim are still available to Christians in the modern day.5 While most Christians express some uncertainty about the will of God, Charismatics combine evangelical fervor with a strong belief in active, supernatural intervention in everyday life.

While Charismatic practices have existed in various forms throughout the history of Christianity, the modern movement is primarily rooted in Pentecostalism,6 which emerged in the United States during the early 20th century.7 Pentecostals embraced continuationism — the belief that miracles and spiritual gifts did not cease with the apostolic era8— placing them in stark contrast to the dominant miracle skeptic, or cessationist views of most other Christians.

Initially derided by mainstream churches, Pentecostalism grew rapidly, particularly among the socially and economically disenfranchised9; from its inception, Charismatic Christianity resonated deeply with marginalized communities by adapting to local cultures and languages. Its preachers often reflected the racial and social backgrounds of their congregations,10 thus challenging traditional ecclesiastical hierarchies and empowering lay participation.

This decentralized dynamic enabled Charismatic beliefs to cross denominational boundaries. The “Second Wave” of Charismatic expansion saw Pentecostal practices take root within established Protestant and Catholic churches,11 eventually receiving endorsement from figures such as Pope Paul VI, who addressed the 3rd International Congress of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal in 1975.12

One influential offshoot of the Second Wave was the "Jesus Freak" movement of the 1970s,13 wherein disillusioned former hippies embraced a stripped-down, radical form of Christianity that often rejected institutional religion entirely. This, in turn, helped pave the way for the “Third Wave” of the Charismatic movement, which further decentralized leadership and encouraged the empowerment of local church leaders.14

Unlike the first two waves—Pentecostalism as a distinct tradition and the Second Wave as a reform movement within established churches—the Third Wave was radically flexible. Loosely unified by a belief in spiritual gifts and the necessity of spiritual warfare, it eschewed formal ecclesiastical structures in favor of dynamic, personality-driven leadership.

While the United States remains an important center for Charismatic Christianity, the movement’s most explosive growth has occurred in the Global South15—particularly in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Asia.16 The absence of a centralized authority—such as the Vatican or a major denominational hierarchy—has allowed Charismatic networks to adapt swiftly to local contexts. Leadership often emerges from the grassroots: individuals with compelling visions and loyal followings may assume pastoral or apostolic authority, frequently bypassing traditional theological training altogether.17

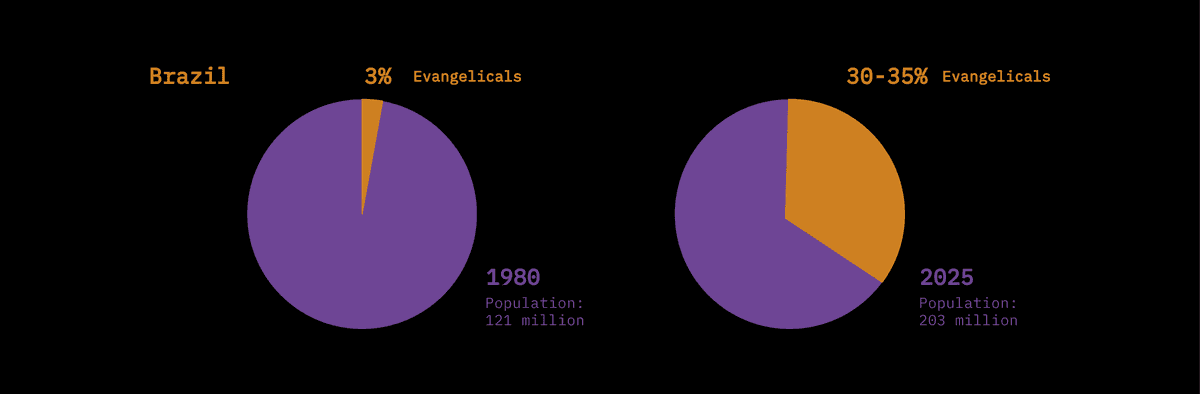

The numbers reflect this shift. In Argentina, evangelicals now make up about 15% of the population.18 In Brazil, they account for roughly 31%19—a remarkable increase in nations that were, until recently, overwhelmingly Catholic.

How Spiritual Gifts Became Political Weapons

A core tenet of many Charismatic movements—especially those aligned with the global right—is the belief in spiritual warfare. In this theological framework, demons and evil spirits are not metaphors but active agents that shape political, cultural, and social realities. While traditional Christian doctrine typically confined demonic influence to personal temptation, Charismatics extend the battleground to encompass institutions, governments, and entire nations.

Central to this worldview is the concept of “territorial spirits”—demonic entities believed to exert influence over specific geographic regions.20 Entire societies can thus fall under divine blessing or demonic domination. In this framework, gay nightclubs,21 abortion clinics22, or foreign governments (like Iran23) are not merely political or moral concerns; they are manifestations of spiritual corruption that must be eradicated as part of a larger cosmic struggle.

Once a person, group, or institution is classified as under demonic control, it is no longer viewed as a legitimate political adversary—it becomes an enemy of God. Within this schema, spiritual warriors are not merely justified, but morally compelled to resist—whether through intercessory prayer, grassroots activism, or direct political intervention. In more radical interpretations, violence itself can be framed as a righteous and divinely mandated act.24

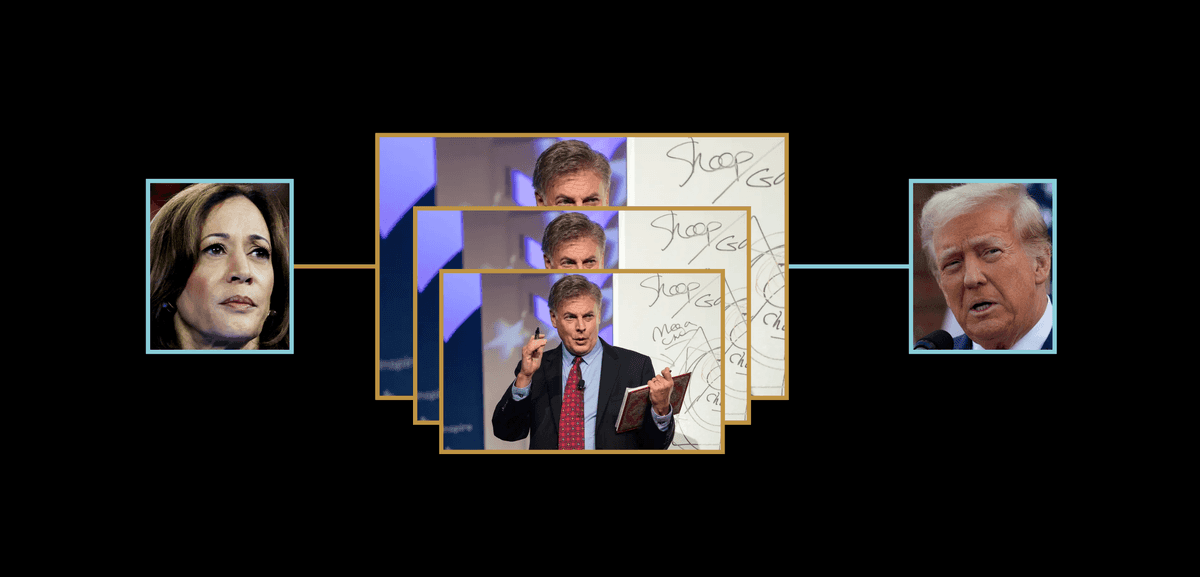

This logic was on display during the 2024 U.S. presidential election, when leading Charismatic figure Lance Wallnau declared that Kamala Harris embodied the "spirit of Jezebel" and that "the devil’s plan" was to make her president.25 By portraying political opponents as agents of Satan, the space for democratic negotiation collapses, and political conflict becomes an existential spiritual war.

It is no coincidence that some of the most dramatic political crises of the past decade — the January 6th insurrection in the United States,26 27, the January 8th attacks on Brazilian government buildings,28 Bolivia’s 2019 coup attempt,29 and South Korea’s December 2024 coup attempt30— have been saturated with the rhetoric of spiritual warfare. As we will examine in the following sections, in each case, Charismatic Christians framed democratic institutions and norms as expendable when confronted with what they perceived as satanic encroachment into political authority.

Blessing Insurrection: Charismatics in the USA

Although the United States gave birth to Pentecostalism—the foundational tradition of the global Charismatic movement—it has long occupied a marginal position within American Protestantism. Mainline denominations have historically viewed hallmark Charismatic practices such as glossolalia (speaking in tongues) and prophecy with suspicion. As recently as 2015, the Southern Baptist Convention prohibited missionaries who engaged in speaking in tongues.31

Adding to the movement’s elusiveness is the fact that many of its adherents do not self-identify as “Charismatic,” complicating efforts to measure its scale. Still, one estimate suggests that approximately 16.4% of Americans were affiliated with a Charismatic tradition in 2020, a notable increase from 6.9% in 1970.32 Yet the reach of Charismatic spirituality extends far beyond these numbers. Half of American churchgoers report experiencing Charismatic phenomena on a regular basis33 and substantial segments of the broader population express belief in divine healing (36%), prophecy (45%), or the prosperity gospel (31%).34

These beliefs have come to shape how many Americans interpret politics, economics, and history—regardless of formal religious affiliation.

From Prophets to Power: The New Theocratic Vision

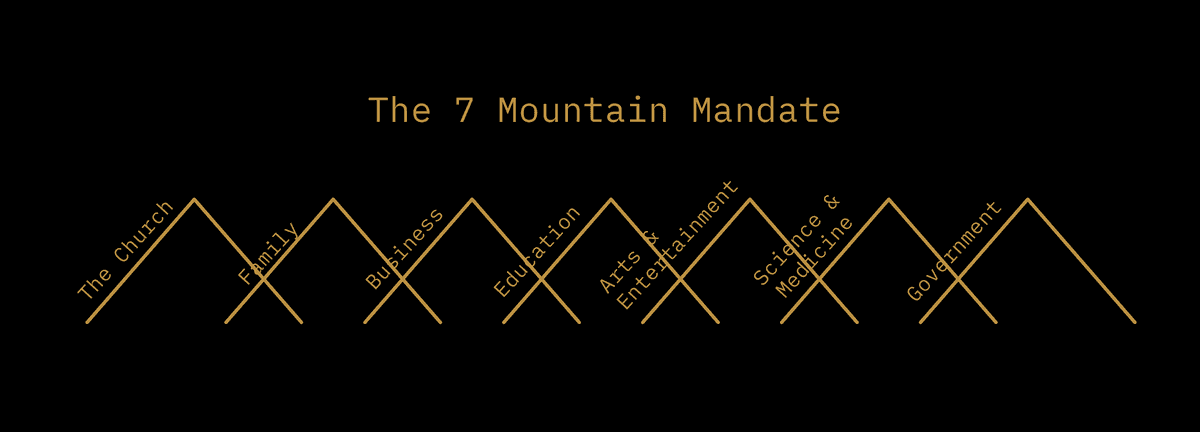

Over the past two decades, a growing segment of Charismatic movements in the United States has aligned itself with Dominionism and Christian nationalism—ideologies which assert that Christians are divinely appointed to govern the nation and that the separation of church and state is a man-made obstacle to God’s will. One of the most influential expressions of this worldview is the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR), a Charismatic theological network that has exerted considerable influence over the religious right. Central to NAR theology is the “Seven Mountains Mandate,” which holds that Christians must take dominion over seven spheres of cultural life: government, education, media, business, family, religion, and the arts.

Support for these views is rising. Roughly 30% of Americans—and a majority of Republicans—now express sympathy for Christian nationalist beliefs. This alignment is especially pronounced among white evangelicals, 67% of whom endorse such ideas, as well as among Hispanic Protestants, where support reaches 57%.35 The growing presence of Charismatic theology within Latin communities has helped fuel the recent rightward shift among Hispanic voters.36

This theological shift has been accompanied by a marked authoritarian turn, with survey data revealing a strong correlation between Christian nationalist beliefs and support for anti-democratic actions. Nearly one in three Christian nationalists believe Trump should have remained in power regardless of the 2024 election outcome, and close to half characterize the January 6 attackers as patriots.37

Postwar Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism—and the broader Charismatic movement—was not always tethered to the American right. In its early decades, the movement embraced an egalitarian spirit and often aligned with the Evangelical left, which once exerted meaningful influence in American political life.38 During the Cold War, however, evangelical Christianity became increasingly linked with anti-communist ideology and nationalist fervor.39

Pentecostalism’s decentralized structure made it uniquely susceptible to external political and cultural shifts. It had historically conformed to the racial hierarchies of the Jim Crow South,40 and in the postwar era it largely reflected and adapted to prevailing social norms.41 Like many religious traditions of the time, it was swept up in a nationwide religious revival marked by increased church attendance,42 heightened public displays of religiosity, and the rise of mass media outreach—particularly televangelism.

Within this revival, two formative currents emerged in the late 1940s: the Healing Revival and the Latter Rain Movement.

The Healing Revival revolved around spectacular displays of divine healing—miracles such as the blind regaining sight or suddenly walking again—which brought national prominence to figures like Oral Roberts. Roberts would eventually pivot toward the prosperity gospel: the belief that faith, positive confession, and financial giving could unlock divine favor and material success.43 In Roberts’s theology, Pentecostal spirituality fused seamlessly with postwar consumer culture, transforming supernatural expectation into middle-class aspiration.

The Latter Rain Movement, by contrast, introduced a series of theological and institutional innovations. It emphasized the restoration of the fivefold ministry—apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors, and teachers—as the proper structure of church leadership, moving Pentecostalism toward more hierarchical and authoritarian frameworks44 and laying intellectual groundwork for movements like the NAR. It also contributed to the diffusion of Anglo-Israelism—the belief that Anglo-Saxons are descendants of the lost tribes of Israel—a racialized theology that would later support ideological alignments between the Evangelical right and Zionist politics.45

Still, it was the broader charismatization of American religion—the diffusion of Pentecostal practices and theology across denominational lines—that ultimately brought these ideas into the American mainstream.

The Long March to Respectability

Until the mid-20th century, Pentecostals remained largely marginalized within American Protestantism, with many mainstream theologians deeming their beliefs and practices heretical.46 Their political activity primarily centered on defending “religious freedom” and shaping public morality, rather than endorsing specific candidates or parties. With culturally conservative elements present in both major political parties, Pentecostals could be found on either side of the aisle.

Owing to the movement’s decentralized and often localized character, its political orientations varied widely. Nevertheless, a persistent undercurrent of Christian nationalism ran through many Pentecostal communities.47

A pivotal development occurred in 1951 with the founding of the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship International. Though nominally a lay Christian business association, the Fellowship functioned as a conduit for Charismatic influence within conservative political circles, forging links between Pentecostal leaders and right-wing business elites. Dominated by Pentecostals, it played a crucial role in normalizing Charismatic practices across both religious and economic spheres.48

Pentecostalism’s political alignment accelerated under Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” which sought to attract disaffected Southern Democrats and reconfigure the Republican base. Nixon’s targeted outreach to evangelicals proved successful, initiating the gradual migration of white Southern evangelicals—including Pentecostals—into the GOP. While the Watergate scandal alienated many evangelicals, some prominent Charismatics, such as Kenneth Copeland, continued to defend Nixon,49 illustrating a growing tendency within the movement to rationalize political loyalty.

The 1988 presidential campaign of Pat Robertson, a prominent Charismatic preacher, marked a key moment in the political ascent of the movement. Though a political outsider, Robertson secured approximately one million votes and 9% of the Republican primary electorate. He subsequently founded the Christian Coalition, which would become a central force in the 1994 Republican Revolution, cementing the institutional presence of the religious right within the GOP. By the early 2000s, evangelical Protestants—including Pentecostals—had become a core electoral base of the Republican Party.

The Apostles of American Power

It was not until the early 21st century that the more radical strands associated with the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) began to migrate from the theological margins into the center of national political life. Rooted in the legacy of the Latter Rain and Shepherding movements, the NAR emphasizes hierarchical spiritual authority and promotes a Dominionist theology asserting that Christians are called to exercise control over all spheres of society. Though still considered fringe in the 1990s, the NAR laid an ideological foundation for a more militant religious politics—one that would gain traction during the Trump era.

A pivotal moment came in 2008, with the selection of Sarah Palin as John McCain’s vice-presidential nominee. Palin, a Pentecostal with documented ties to NAR figures such as Thomas Muthee, galvanized the religious right in ways McCain could not. Although the ticket ultimately lost, Palin’s candidacy marked a turning point: Charismatic leaders began to see national political power as attainable and recognized that their networks could mobilize voters well beyond traditional denominational boundaries.50

During the 2016 Republican primaries, many Dominionist leaders initially backed Senator Ted Cruz, whose father was a well-known Dominionist preacher.51 But key NAR figures—most notably Lance Wallnau—threw their support behind Donald Trump.52 Long before Trump’s victory appeared plausible, Wallnau had cast him as a “modern-day Cyrus,” a pagan king anointed by God to defend Israel. In this theological framing, Trump’s personal transgressions were irrelevant; he had been divinely appointed for a sacred purpose.

This narrative allowed Charismatic leaders to justify unwavering allegiance to Trump. Even after the release of the infamous Access Hollywood tapes—in which Trump was recorded making sexually aggressive and misogynistic remarks—they did not waver. While some Republicans distanced themselves, Charismatic leaders doubled down, casting Hillary Clinton not merely as a political adversary but as an existential threat aligned with Satan himself 53.

The contrast with Watergate was stark. Many evangelicals abandoned Nixon as revelations mounted. In 2016, however, most Charismatic leaders stood by Trump. Figures like Russell Moore, who publicly voiced concern54 were notable exceptions. Ultimately, evangelical loyalty played a critical role in securing Trump’s electoral victory.55

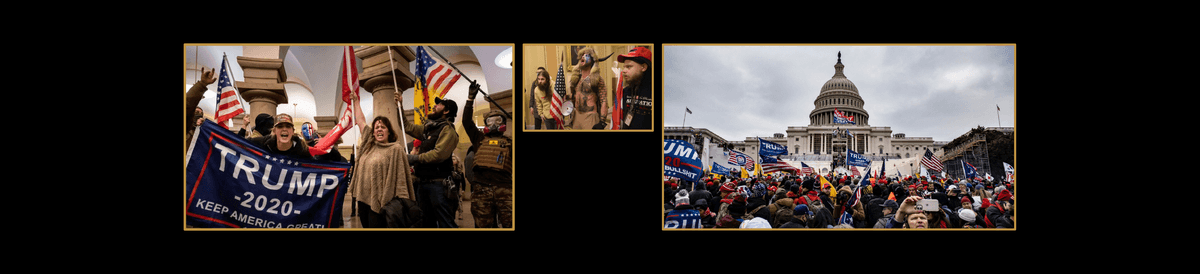

Holy War at the Capitol: The Theology Behind January 6th

Trump’s unexpected victory in the 2016 election was, for many Charismatic Christians, not merely a political surprise—it was the fulfillment of prophecy and a powerful affirmation of their faith. Within these networks, Trump was never just a Republican candidate; he was God’s anointed, divinely chosen to restore America’s greatness.56 His presidency was proclaimed as Spirit-filled and supernaturally guided.57 As the 2020 election approached, Charismatics did not merely hope for his reelection—they proclaimed it inevitable, the fulfillment of a divinely ordained prophecy.58

When Trump lost, the response was not just political denial—it was a theological crisis. Kenneth Copeland, one of the most prominent Charismatic leaders, responded to news of Joe Biden’s win by laughing maniacally from the pulpit, refusing to acknowledge the legitimacy of the outcome.5960

Amid this spiritual fervor, the QAnon conspiracy theory found fertile ground.61 Its apocalyptic narrative fused seamlessly with Charismatic theology, offering a compelling explanation for Trump’s loss: it was not a defeat, but a divinely orchestrated strategy in a larger spiritual battle against a cabal of satanic elites.62

The first phase of that mobilization came in the form of the “Jericho Marches.” Modeled after the biblical siege of Jericho, participants encircled centers of political power—including the U.S. Capitol— praying for supernatural intervention to overturn the election.63 Despite repeated certifications of Biden’s victory, many remained convinced that God would miraculously reinstate Trump.

As court challenges collapsed, hope narrowed to a single date: January 6th. A theory spread that Vice President Mike Pence—long considered an ally of the Christian right—had the authority to reject the electoral results. When he refused, he was cast as a Judas figure.64

In the wake of the January 6th insurrection, many anticipated a national reckoning. The breach of the U.S. Capitol stunned the country, prompting condemnation from religious leaders across a wide spectrum. But among many Charismatic Christians, the response was not repentance—it was rationalization. Some initially blamed Antifa, casting the attack as a false-flag operation designed to discredit Trump supporters.67 Over time, they shifted tactics: condemning the violence while insisting the election had been stolen.68 By the approach of the 2024 campaign, even that ambiguity had disappeared. The insurrection was no longer framed as an excess—it had become a righteous response to spiritual tyranny.69

QAnon, an internet hoax rooted in 4chan imageboard posts, did not fade when its original poster vanished. Instead, it merged seamlessly with the theology of Charismatic Christianity.70 It provided a theological framework in which political struggle was recast as cosmic warfare. Joe Biden was depicted as a vessel of demonic influence, while Trump and his allies were heralded as warriors anointed to battle against darkness. QAnon was no longer a fringe movement; it had become part of the ideological bloodstream of the American right.71

One of the most prominent early examples of this fusion was Marjorie Taylor Greene. Elected in 2020, she openly promoted QAnon71 and declared herself a Christian nationalist73 Though initially sidelined,74 she rose rapidly—becoming a prolific GOP fundraiser,75 and eventually chairing the Elon Musk-affiliated United States House Oversight Subcommittee on Delivering on Government Efficiency.76 Her rhetoric merged spiritual warfare with conspiracy politics. After Pope Francis’s death—a figure many evangelicals viewed with suspicion—she declared that “evil is being defeated by the hand of God.”77

The consolidation of Charismatic power became unmistakable in 2023, when Louisiana congressman Mike Johnson was elected Speaker of the House. A relatively obscure figure on the national stage, Johnson was championed by Dutch Sheets, one of the key NAR leaders behind the pre-January 6th mobilization.78

As the 2024 election neared, Charismatic leaders and their followers remained confident. The Biden administration was widely regarded within these circles as spiritually illegitimate79 and the late substitution of Kamala Harris as the Democratic nominee did little to alter that perception.

By the time Donald Trump returned to the White House in 2025, Charismatic Christianity—particularly its Dominionist wing—had entrenched itself as a dominant ideological force within the Republican Party. For millions of Charismatic believers, Trump’s political resurgence is not simply a partisan triumph—it is the realization of divine prophecy.80 81

This theological framework extends well beyond the domestic sphere. Charismatic leaders are among the most fervent defenders of Israel’s war in Gaza, framing the conflict as a cosmic battle between good and evil. Christians United for Israel, the movement’s most prominent institutional vehicle, views support for Israel not as a matter of policy, but as a litmus test of spiritual fidelity. In this logic, critics of Israeli policy are not simply wrong—they are enemies of God, whose voices must be silenced.

Brazil: Evangelical Empire and Bolsonaro’s Rise to Power

Although Charismatic Christianity originated in the United States, few countries have been more profoundly reshaped by it than Brazil. Over the past few decades, Brazil has undergone a sweeping religious transformation. In the 1970s, 91% of Brazilians identified as Catholic and only 5% as Protestant. Today, that gap has narrowed dramatically: about 50% identify as Catholic, and 31% as Protestant—primarily evangelicals.82 With Charismatic practices gaining traction within Catholicism as well, nearly half of all Brazilians now engage in Charismatic forms of worship83 — one of the highest rates in the world, both proportionally and in absolute numbers. Some projections even suggest that Protestantism could become Brazil’s largest religion by 2032.84

For a time after the country’s return to democracy, Pentecostalism found an unlikely ally in the left-wing Workers’ Party (PT) and its leader, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, rooted in shared ties to Brazil’s urban poor. But by the mid-2010s, the alliance had unraveled. As the Workers’ Party embraced increasingly progressive social policies, tensions with the socially conservative Pentecostal leadership deepened.85 By 2018, the break was complete: Charismatic and Pentecostal voters overwhelmingly backed far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro,86 playing a pivotal role in his rise to power.

From Local Organizing to National Power

The Charismatic tradition in Brazil can be traced back to the urban migrations of the 1950s, when millions of rural Brazilians poured into cities and settled in sprawling informal communities known as favelas. The Catholic Church, bound by rigid hierarchies and slow-moving institutions, struggled to adapt to these rapidly shifting social realities. Evangelicals, by contrast, faced few bureaucratic hurdles and built churches wherever people settled. In one poor settlement in Salvador, an anthropologist observed a striking imbalance: one Catholic church compared to eighty evangelical ones.87

During Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964–1985), evangelicals largely avoided direct political engagement. But with the return to democracy and the 1988 Constituent Assembly, they began to organize. Under the slogan “Brother votes for Brother,” the Assembly of God—the country’s largest evangelical denomination—managed to elect a handful of candidates.88 Though initially a marginal force, the movement had found its political footing.89

As Brazil’s evangelical population grew, so did its political influence. Their alliances shifted tactically—sometimes conciliatory toward the left, other times firmly opposed—but their core objective remained constant: leveraging their power in Brazil’s fragmented Congress to defend conservative social policies. In 2003, they formalized their rising clout with the creation of the Evangelical Parliamentary Front (Frente Parlamentar Evangélica).

During the 2010s, as the Workers’ Party embraced increasingly progressive social policies, the evangelical bloc shifted into open confrontation with the left. Evangelical legislators played a pivotal role in the 2016 impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, marking a watershed moment: from a marginal political force to capable of toppling a sitting government.90

The Church as State: Evangelical Social Control in the Favelas

Evangelical churches have embedded themselves deeply in the everyday lives of their members by filling gaps left by the state. Although Workers’ Party governments expanded social programs, major needs persisted. Evangelical churches stepped in, providing everything from food aid and job placement to addiction treatment.91 92 93 Their ability to form responsive, close-knit communities fostered a powerful sense of belonging—especially among marginalized urban populations. This deep integration gave them extraordinary influence over the political outlook and behavior of their followers.

The decentralized nature of Charismatic Christianity — where local pastors wield wide autonomy — has led to some theologically unique and politically potent outcomes. One of the most extreme is the Terceiro Comando Puro (Pure Third Command), which controls the "Israel Complex" of favelas in Rio de Janeiro. Led by Álvaro Malaquias Santa Rosa — better known as Peixão (“Big Fish,” a reference to Jesus) — the group blends narco-trafficking with religious sectarianism. Often described as “Narco-Pentecostals,” they present Jesus as the divine ruler of their territories.94

Their control is significant: they’ve shut down Catholic churches,95 and refuse to work with non Evangelicals. They have even adopted the Star of David as part of their iconography, drawing from Christian Zionist and end-times theology.96 While an extreme case, the fusion of evangelical theology with organized crime underscores the movement’s remarkable flexibility — its ability to reshape, and be reshaped by, Brazil’s fragmented social order.

Broadcasting Belief

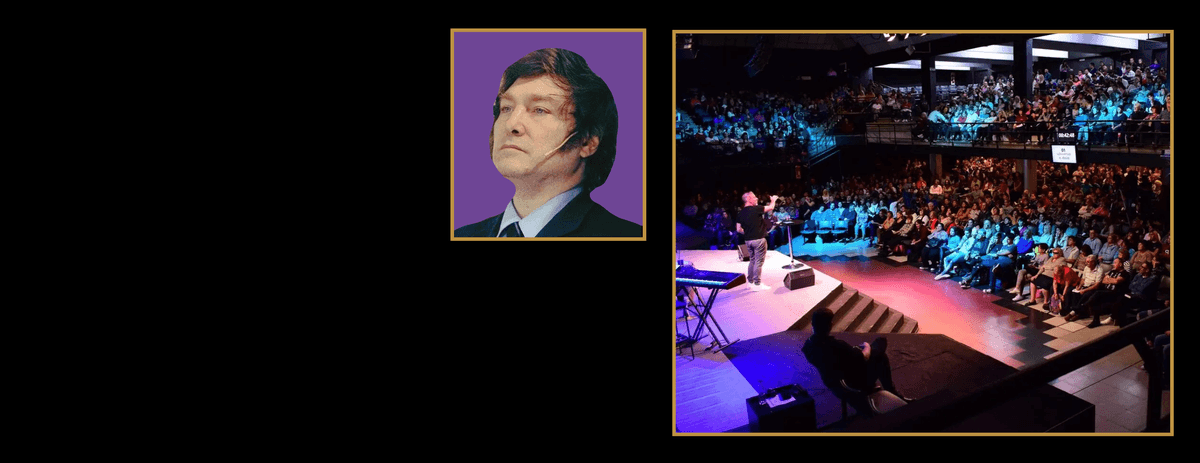

Evangelical influence in Brazil expanded not only through pulpits but through the airwaves. Bishop Edir Macedo, founder of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus, or IURD), built an empire that blurred the lines between religion, business, and politics. With a net worth estimated at $1.8 billion97 Macedo owns TV Record—Brazil’s second-largest television network.98

By 2012, Record’s political influence had become undeniable. President Dilma Rousseff appointed Macedo’s nephew, Senator Marcelo Crivella — a prominent IURD bishop — as Minister of Fishing and Aquaculture.99 Crivella later served as mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s second-largest city, from 2017 to 2020. His administration blurred the boundaries between religion and state, channeling public funds toward IURD projects100 and distancing the city from Carnival celebrations, which many Evangelicals regard with hostility.101 His administration ultimately ended in scandal when he was arrested on graft charges in 2020, but he remains in Congress and is a powerful ally of Jair Bolsonaro.

Macedo’s media empire played an even more decisive role in Jair Bolsonaro’s 2018 campaign. After Macedo publicly endorsed Bolsonaro, TV Record provided overwhelmingly favorable coverage. Former employees alleged they were pressured to support Bolsonaro, and in return, the network was granted exclusive interviews and privileged access after his victory.102

WhatsApp and Digital Mobilization

The most direct way evangelicals shape Brazilian politics today is through social media. A 2024 study by influencer agency Influency.me found that eight of Brazil’s top ten Christian Instagram influencers were evangelical.103

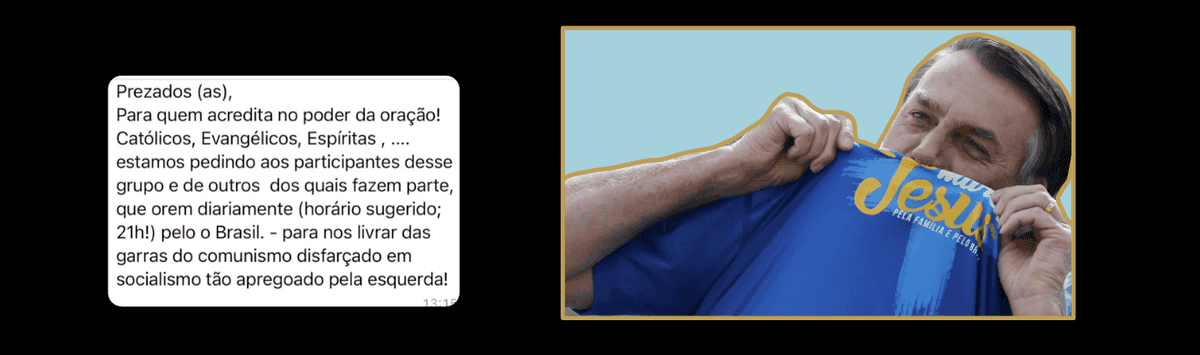

This online dominance proved critical during the 2018 election, when evangelical networks played a key role in spreading far-right disinformation, particularly through WhatsApp. Even before election day, it was clear that WhatsApp was helping boost Bolsonaro’s candidacy104 prompting, too late, for Meta to revise the platform’s policies.105 Although the specific role of evangelicals was less understood at the time, their efforts helped propel Bolsonaro to victory.

The alliance between Bolsonaro and evangelical leaders didn’t begin in 2018. In 2013, right-wing Christians mobilized against Fernando Haddad—then Minister of Education and later the Workers’ Party’s presidential candidate—over the so-called “gay kit,” a proposed educational initiative aimed at combating homophobia in schools. Evangelical pastors framed it as an attack on traditional family values and an effort to impose “gender ideology.” Their pressure campaign led President Dilma Rousseff to veto the program.”106

Years later, the same rhetoric reemerged—amplified and weaponized—during the 2018 campaign. Evangelical networks revived the “gay kit” controversy as part of a broader moral panic, portraying the Workers’ Party as not just corrupt, but spiritually perverse. Through tightly knit digital communities and relentless WhatsApp campaigns, they reinforced reactionary worldviews and deepened political polarization.107

2022 Election and the Bolsonaro Coup Attempt

In the 2022 presidential election, Bolsonaro sought to replicate the same formula that had propelled him to power in 2018: securing the backing of influential church leaders and mobilizing evangelical voters through digital disinformation. But this time, he faced Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the popular former president who had been barred from running in 2018 as part of a right-wing judicial campaign to sideline him.108 Given the deep unpopularity of Bolsonaro’s government at the time, the extremely popular Lula was widely expected to win easily, perhaps even securing a rare first-round victory in Brazilian politics.

Yet the race proved far tighter than anticipated. Bolsonaro and Lula were separated by only a few points in the runoff. While most demographic groups swung sharply toward Lula, evangelical voters remained comparatively loyal to Bolsonaro, shifting only modestly—about four points.109 Although poorer evangelicals were less supportive of Bolsonaro,110 they are comparatively less left-wing than similarly poor catholics, and the continuous growth of the evangelical population since Lula’s last candidacy in 2010 helped keep Bolsonaro competitive.

After his defeat, Bolsonaro—echoing Donald Trump—immediately alleged widespread electoral fraud.111 His claims were rejected by the courts, but they found deep resonance among his evangelical base. Many pastors and believers invoked the language of spiritual warfare, framing Lula’s victory as the work of demonic forces.112 In the weeks following the election, evangelical and right-wing rhetoric grew increasingly apocalyptic, mirroring the spiritualized discourse that had fueled the January 6th Capitol insurrection in the United States. Prominent U.S. right-wing figures like Tucker Carlson even voiced support for Bolsonaro’s movement.113

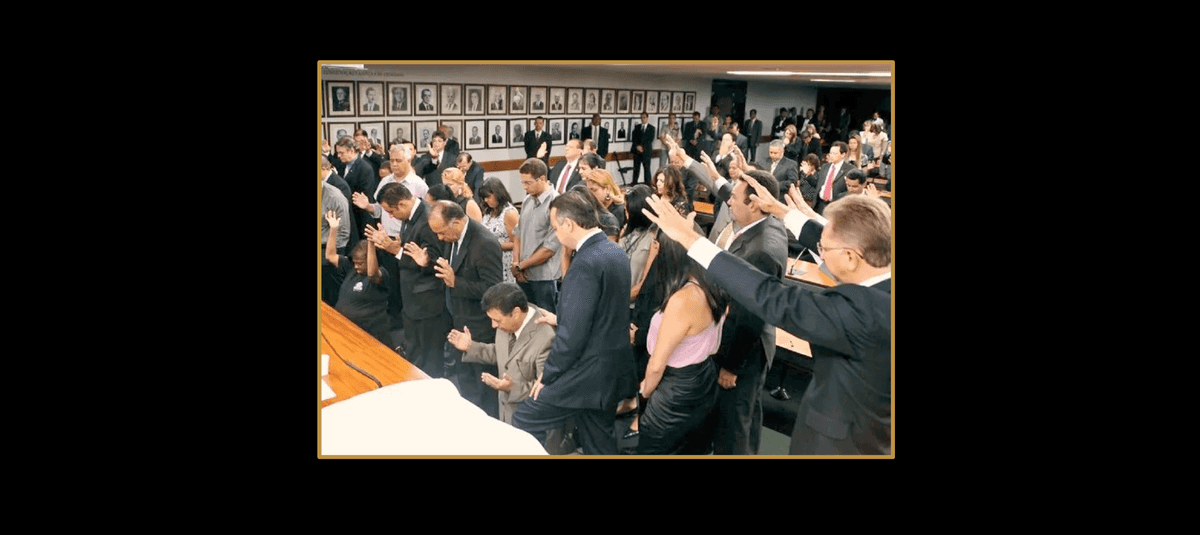

On January 8, 2023, as thousands of Bolsonaro supporters stormed Brazil’s Congress, Supreme Court, and presidential palace, Charismatic Christians played a visible role. One viral post declared: “Brazil belongs to Lord Jesus! The Senate is our church! The Senate is the church of the people of God.”

A post-riot survey by Atlas/Intel revealed the extent of evangelical alignment with the coup attempt: 64% of Brazilian evangelicals supported a military coup. Nearly a third (31%) supported the invasion of the capital, compared to only 18% of Brazilians overall. Just 28% of evangelicals believed Lula’s election was legitimate.114 115

Although Bolsonaro has since been charged for his role in the coup attempt, evangelical power has only grown. Evangelical leaders have aggressively pushed revisionist narratives about January 8th116 while Bolsonaro’s allies in Congress continue to demand amnesty. Whatever Bolsonaro’s personal future, the evangelical bloc has emerged stronger: it now represents more than 40% of Brazil’s Congress.117 With Lula increasingly forced to court evangelical leaders,118 it is clear that Charismatic Christianity will shape Brazilian politics for years to come.

A Holy War in Seoul: Charismatic Protestantism and the 2024 South Korean Coup

While a slight majority of South Koreans are religiously unaffiliated, Christianity is the country’s largest single self-identified religious group. This is particularly striking given that Christianity only began gaining traction on the peninsula in the early 20th century.119 Today, roughly two-thirds of South Korean Christians are Protestant,120 and among them, Charismatic and Pentecostal expressions dominate.121 122

Historically, Protestantism and Catholicism in Korea have aligned with opposing political camps: Protestantism with conservatism and anti-communism; Catholicism with liberal and democratic movements. While there have been exceptions—such as Protestant engagement with Minjung theology (Korea’s version of liberation theology) and the emergence of right-wing Catholic Charismatics—this overall pattern has endured. Understanding this religious-political divide is crucial for grasping how Charismatic Protestantism evolved into a driving force behind South Korea’s far-right movements.

Protestantism’s Political Roots

Protestants first emerged as a significant political force during the March First Movement of 1919, a nonviolent uprising against Japanese colonial rule. Though Protestants made up only 1–2% of the population at the time, they accounted for roughly 20% of those arrested.123 Their outsized participation tied Protestantism to Korean nationalism, fueling conversions across the peninsula.

After Korea’s liberation and subsequent division, the North’s secular policies prompted many Christians to flee south, to the right wing US backed regime, solidifying their ties with right wing politics.124 The South’s first president, Syngman Rhee—a Protestant—cemented the alignment between Protestantism and anti-communist authoritarianism by filling the U.S.-backed regime with fellow Christians. Despite their minority status, Protestants gained disproportionate influence in postwar South Korean society.125

During the Cold War, Protestant churches were closely aligned with South Korea’s military dictatorships. Meanwhile, Catholic institutions gradually emerged as centers of pro-democracy activism. This divide paved the way for the explosive rise of Pentecostalism and Charismatic Christianity, which flourished under authoritarian rule due to shared ideological commitments and state protection.126

From Cell Groups to Political Networks

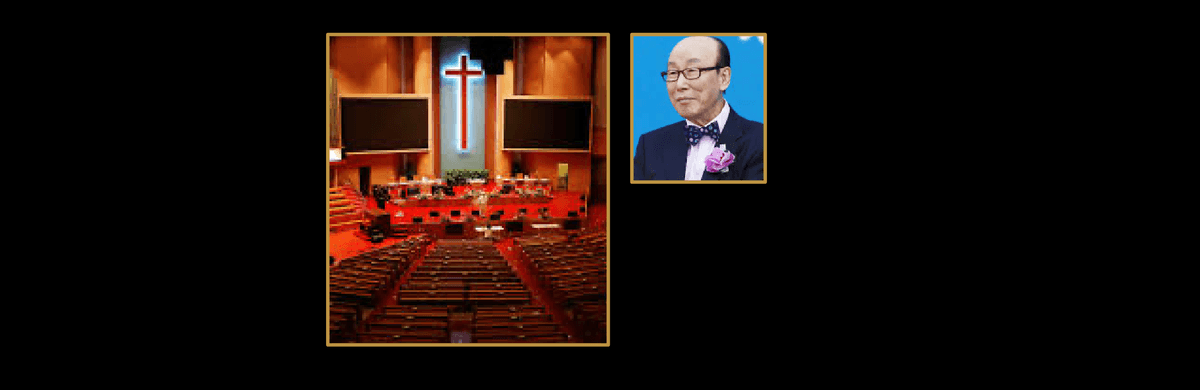

The explosive growth of Charismatic Christianity in South Korea can be largely attributed to Pastor David Yonggi Cho. After studying at the Pentecostal-backed Seoul Full Gospel Theological Seminary (now Hansei University), Cho founded Yoido Full Gospel Church in 1958,127 under the auspices of the Assembly of God denomination. Initially achieving only modest success, Cho’s encounter with the teachings of American evangelist Oral Roberts—and his adoption of the prosperity gospel—dramatically accelerated the growth of his congregation.128

However, rapid expansion soon exposed a major bottleneck: the traditional centralized pastoral model could not sustain the growth he was hoping to achieve. Faced with the twin personal pressures of his military conscription and burnout, Cho devised a groundbreaking innovation—the "cell group" model. Rather than relying solely on large weekly services, Cho decentralized his ministry, organizing members into small groups of about a dozen people. These cells met independently for Bible study, fellowship, and—critically—evangelism and recruitment.129 When a group grew large enough, it would split, creating an exponential cycle of expansion.

Although the cell groups remained doctrinally anchored to Cho’s leadership, they operated with considerable autonomy, relieving pressure on the central church structure while enabling continuous and scalable growth. This system eventually propelled Yoido Full Gospel Church to become not only the largest megachurch in South Korea, but the largest in the world.130 Cho’s model has spread internationally, profoundly reshaping charismatic and Pentecostal church organization worldwide.

Meanwhile, the South Korean government’s tolerance of charismatic Protestant churches—rooted in the shared anti-communist fervor—allowed right-wing congregations to expand freely even under authoritarian rule, at a time when broader political expression was heavily restricted. This state favoritism proved crucial,131 providing a protected space for charismatic churches to grow rapidly.

Evangelical Participation in Politics

Following South Korea’s democratic transition in the late 1980s, evangelicals remained aligned with the political right but generally avoided direct electoral engagement. That changed in the wake of back-to-back victories by liberal Catholic presidents: Kim Dae-jung in 1997 and Roh Moo-hyun in 2002.

Kim’s presidency, despite its progressive domestic agenda and overtures to North Korea via the Sunshine Policy, was initially dismissed by the Protestant right as an outlier.132 But Roh’s narrow and unexpected victory133 in 2002 intensified anxieties. Conservatives had expected to reclaim the presidency, and Roh’s win shattered those assumptions.

Tensions escalated further in 2004 when an evangelical-backed attempt to impeach Roh backfired. Instead of weakening him, it led to a landslide victory for his Uri Party, which delivered South Korea’s liberals their first-ever absolute majority in the National Assembly since the return to democracy. For many Protestant conservatives, this was a wake-up call. Liberal governance was no longer a temporary deviation—it was now framed as an existential threat. Evangelical leaders began invoking the language of spiritual warfare, painting politics in apocalyptic, moral terms.

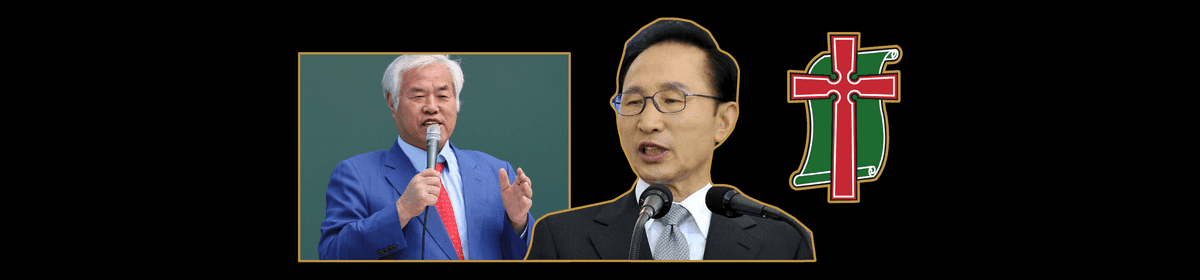

In response, the Protestant right split into two main strategic camps. One faction tried to establish explicitly Christian political parties, often under the leadership or backing of megachurch pastors. These parties ran on platforms focused on defending Christian values against threats like homosexuality, Islam,134 and secularism. One of the most prominent leaders of this effort was Pastor Jeon Kwang-hoon.135 However, these parties consistently failed to gain traction—unable to cross the minimal threshold to enter the legislature.

The other, more pragmatic faction pursued power through coalition-building. Aligning themselves with broader right-wing political forces, they joined the emerging New Right movement. This strategy proved far more effective. It culminated in the 2008 election of Lee Myung-bak—a Presbyterian elder and corporate executive—as president. By working within the existing conservative establishment, evangelical leaders were able to secure a durable and more influential political foothold.136

Since then, the alliance between South Korea’s evangelical right and the conservative establishment has only grown stronger. Evangelical leaders effectively gained veto power over major policy initiatives whenever conservatives held power. 137 Their influence was particularly visible in opposing LGBTQ+ rights and derailing efforts to engage with North Korea. They also mobilized against seemingly unrelated issues—such as blocking legislation for Islamic bonds—by deploying Christian nationalist rhetoric. In one case, a conservative lawmaker justified his vote by claiming pastors had warned the bonds would "fund terrorism."138

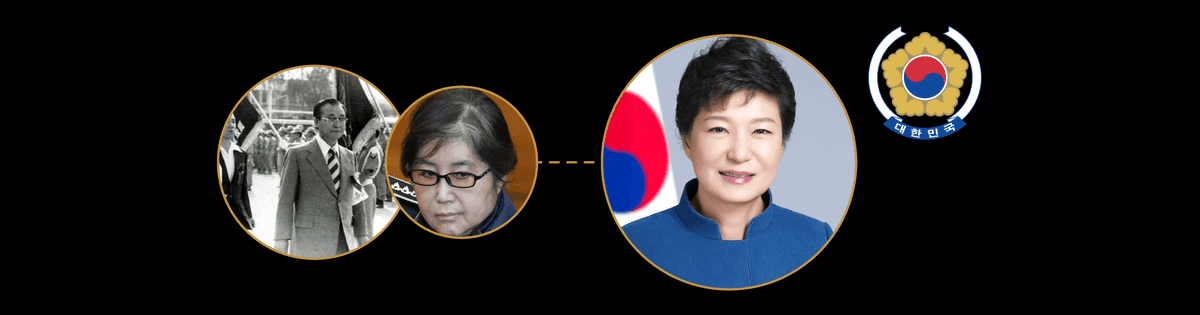

Park Geun-hye’s Charismatic Cult

One of the clearest illustrations of the deep entanglement between Charismatic Christianity and South Korea’s conservative politics came with the 2016 scandal that ultimately led to President Park Geun-hye’s impeachment.

At the heart of the controversy was Park’s unusually close relationship with Choi Soon-sil, daughter of Choi Tae-min—a former Buddhist monk who had founded the Church of Eternal Life, a syncretic sect blending elements of Buddhism, shamanism, and Charismatic Christianity.139 Far from an outlier, this fusion reflected Korea’s broader pattern of Charismatic-influenced religious syncretism.

When it emerged that Choi Soon-sil had been granted unauthorized access to classified government documents, played a major role in policy decisions, and extorted corporate donations to her own foundations, public outrage was swift and overwhelming.140 The perception that the presidency had been compromised by a cult-like religious group triggered some of the largest mass protests in South Korea’s democratic history. Facing mounting pressure, even members of Park’s own party abandoned her, leading to her impeachment.141

While a handful of hardline evangelicals and far-right groups attempted to defend Park—often resorting to Cold War-era anti-communist rhetoric and borrowing tactics increasingly associated with Trump-era politics in the United States142—the defense failed to gain serious traction. With over 80% of the public supporting impeachment,143 mass evangelical mobilization would have been political suicide.

In the early presidential election that followed, major Protestant organizations—including the influential Christian Council of Korea—pointedly declined to endorse any candidate.144 Their silence signaled the extent of the damage: the Park scandal had deeply undermined Protestant political legitimacy.

Moon Jae-in and the Radicalization of Evangelicals

Although many Charismatic Christians largely withdrew from frontline politics after Park Geun-hye’s impeachment, this passivity would soon be viewed by evangelical leaders as a costly mistake. The election of progressive candidate Moon Jae-in in 2017 marked the beginning of a new phase of radicalization within South Korea’s Protestant right.

Once in office, Moon pursued a series of liberal reforms, including expanded access to abortion,145 anti-discrimination protections for LGBTQ+ individuals, and a more conciliatory policy toward North Korea. To many conservative evangelicals, these initiatives were not just policy disagreements—they were interpreted as existential threats to Korean Christianity itself. Prominent Charismatic leaders increasingly depicted Moon not merely as a political opponent, but as a vessel for satanic forces.146

Despite Moon’s Democratic Party holding a parliamentary majority, the Protestant right demonstrated its continued ability to mobilize large street protests and apply sustained public pressure.147 Several of Moon’s signature initiatives were either abandoned or significantly diluted in response to evangelical backlash.148

Heading into the 2020 legislative elections, Protestant leaders sought to build on this momentum by unifying the conservative forces.149 The leader of this new political front was Hwang Kyo-ahn—a devout Evangelical Protestant, former prime minister, and one of their own.150 Hopes were high that Hwang could reclaim the prime ministership and potentially the presidency.

But the gamble failed. Hwang’s association with the Protestant right became a political liability due to their far-right demands consistently alienating moderates.151 The United Future Party, under his leadership, suffered a historic defeat—the worst electoral result for the South Korean right since 1960.

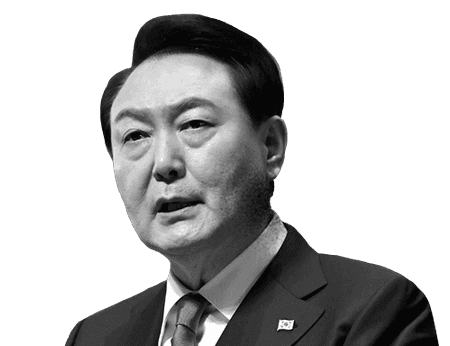

Margins: Evangelicals and the 2022 Election

Once again, direct evangelical efforts to dominate South Korea’s electoral politics had fallen short. Hwang Kyo-ahn, once heralded as the Protestant right’s favored candidate, saw his popularity collapse under widespread public rejection. Instead, the conservative nomination went to Yoon Suk-yeol, a former prosecutor and political outsider with no prior experience in elected office.152

Although Yoon was a nominal Catholic and lacked deep ties to the religious right, Charismatic Protestant networks quickly recognized him as their best available vehicle for reclaiming the presidency. Rallying behind his candidacy, evangelical leaders redirected their formidable organizational power toward ensuring his victory.

Yoon ran on a combative anti-establishment platform, positioning himself against liberal elites and progressive values. The election, one of the closest and most bitterly contested in South Korean history, ended in a narrow conservative win.

Much of the media coverage emphasized Yoon’s use of anti-feminist rhetoric to appeal to disaffected young male voters.153 While this strategy did help broaden his coalition, it obscured a deeper reality: the Protestant right remained the true organizational backbone of his campaign. Evangelical megachurches supplied not just moral endorsement, but also money, infrastructure, and disciplined grassroots mobilization.

Their then longstanding project to unify the South Korean right culminated in Ahn Cheol-soo’s endorsement of Yoon, 154 a move that facilitated the merger of Ahn’s party with the United Future Party to form the rebranded People Power Party (PPP). While anti-feminist backlash energized parts of Yoon’s base, it was the evangelical infrastructure that proved decisive. Without it, Yoon’s path to the presidency would likely have failed.

Yoon’s Fragile Presidency

Despite securing the presidency, Yoon Suk-yeol entered office with sharply limited room to maneuver. The Democratic Party retained control of the National Assembly, leaving the legislature firmly in the hands of his political opponents and effectively reducing Yoon to a lame-duck president from the outset.155

With the 2024 legislative elections looming, Yoon and his evangelical allies placed enormous political and symbolic weight on regaining a conservative majority. Victory, they argued, would finally enable them to implement a sweeping right-wing agenda and “reclaim the nation” from what they framed as liberal corruption. One prominent evangelical-led campaign warned of an impending “homosexual dictatorship” if progressives held onto power156—a slogan that encapsulated the fusion of culture war panic and spiritual warfare rhetoric driving the right’s mobilization.

But the strategy failed. Not only did the Democratic Party retain its majority, it did so more decisively than many polls had predicted. The result dealt a severe blow to Yoon’s domestic ambitions and left his administration paralyzed. For Yoon—whose anti-communist worldview aligned closely with that of the Protestant right, even if he did not fully share their theology—this outcome was intolerable.

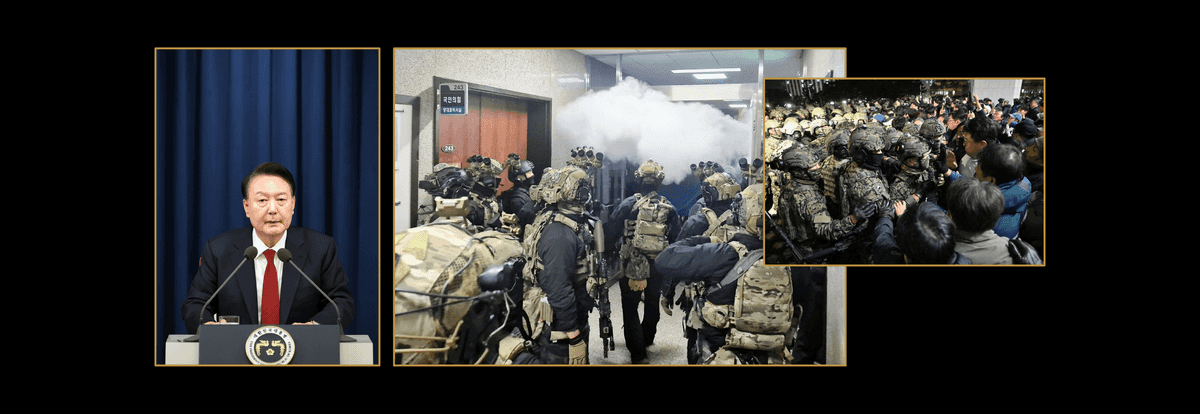

Attempted coup

On December 3, 2024, at 22:27 Korea Standard Time, President Yoon Suk-yeol took to national television to issue an emergency address. Accusing the opposition-controlled legislature of betraying the nation, he declared: “To safeguard a liberal South Korea from the threats posed by North Korea’s communist forces and to eliminate anti-state elements plundering the people's freedom and happiness, I hereby declare emergency martial law.”157

Military units were immediately dispatched to the headquarters of the National Election Commission to investigate fabricated allegations of foreign vote tampering—claims that had been circulating for weeks within far-right and evangelical circles.158 The rhetoric closely mirrored conspiracy theories promoted by Charismatic Protestant networks, which portrayed the 2024 legislative defeat as the result of spiritual sabotage by North Korea and China.

The attempt to overturn democratic governance ultimately failed. Within hours, Yoon’s plans unraveled. Massive public mobilization, immediate condemnation from civil society, refusal by key military commanders to comply, and swift institutional pushback brought the coup attempt to a halt.

Yoon was quickly suspended from office, and impeachment proceedings began almost immediately.159 By April 2025, he was formally removed. A new presidential election was scheduled for June 3, 2025.

Unlike in 2017, Yoon’s base did not quietly accept defeat. Instead, the failed coup further radicalized South Korea’s Protestant right. Prominent evangelical leaders claimed that Yoon’s impeachment had been orchestrated by communist agents and foreign powers, particularly Beijing and Pyongyang.160 Pastor Jeon Kwang-hoon, a longtime figure on the Protestant far right, emerged as a central figure in the backlash. Framing the crisis in overtly spiritual terms, he denounced South Korea’s courts and political institutions as tools of demonic corruption.161

Far-right activists, many with evangelical ties, attempted to block Yoon’s removal from the presidential compound.162 Their messaging drew heavily from “spiritual warfare” theology, portraying political conflict as a cosmic struggle between divine order and satanic subversion. While evangelical leaders did not directly organize the coup, their apocalyptic worldview created the moral framework in which such an attempt could be imagined, and justified.

For the first time since South Korea’s democratic transition, a political tendency—backed by an ideologically militant religious base—attempted to seize power through extralegal means. In the lead-up to the presidential election that followed Yoon’s impeachment, supporters stormed a district court on January 19, 2025, after it issued an arrest warrant for him—an event reminiscent of January 6 in the United States and January 8 in Brazil.

For the 2025 election, the People Power Party nominated Yoon’s labor minister, Kim Moon-soo, as its candidate. Kim initially refused to condemn the declaration of martial law and expressed regret only after receiving Yoon’s endorsement, an endorsement he had actively sought. Despite the party’s direct association with an insurrection, Kim secured 41% of the vote, compared to 49% for Lee Jae-myung, Yoon’s opponent in the 2022 election, a strikingly strong result given the circumstances.

Though not the architects of the coup, the Protestant right had helped shape the ideological conditions that made it possible. Their theology of divine mandates, national purity, and spiritual warfare laid the groundwork for justifying radical action. Even in defeat, the movement was not chastened. Instead, it emerged more convinced than ever that political compromise was a form of surrender—and that only divine authority could restore the nation’s true course.

Pact with Power

Charismatic Christianity has solidified its role as a foundational pillar of far-right political coalitions across the globe. Although the January 6th insurrection failed to overturn the 2020 U.S. presidential election, it revealed the extraordinary mobilizing power of Charismatic networks—and, crucially, their ability to preserve loyalty even in the wake of catastrophic defeat. By reframing Donald Trump’s loss not as a legitimate electoral outcome but as a spiritual injustice, Charismatic leaders maintained cohesion within their base. Support for Trump—and for reactionary politics more broadly—was transformed from a matter of policy preference into an article of faith.

This pattern is not confined to the United States. In Brazil and South Korea, Charismatic and evangelical churches have retained their political influence even after openly backing failed coup attempts. Their theological framing enables a remarkable resilience: defeat is not interpreted as failure, but as the temporary advance of demonic forces. Political legitimacy becomes secondary to spiritual warfare.

It is precisely this capacity for ideological durability that makes Charismatic Christianity so valuable to the global right. It offers more than just an electoral base—it provides a metaphysical justification for loyalty, sanctifies authoritarian leadership, and nullifies the consequences of political loss. Leaders aligned with these movements are not merely supported; they are understood to be divinely appointed instruments of providential history. In return, they are expected to safeguard religious privileges and advance a socially conservative moral agenda—an arrangement to which most far-right politicians are already ideologically predisposed.

This dynamic is now unfolding in Argentina. President Javier Milei’s alliance with ACIERA represents not simply a pragmatic coalition, but an ideological fusion—embedding Charismatic actors directly within the administrative apparatus of the state. Should Milei suffer electoral setbacks—such as in the upcoming midterm contests—the infrastructure is already in place to contest the results, delegitimize the process, and reframe defeat as a spiritual betrayal. The language of spiritual warfare is not merely metaphorical—it is mobilizational doctrine.

By casting every political contest as a cosmic battle between divine order and demonic subversion, Charismatic movements render democratic norms, legal processes, and civil liberties provisional at best. These instruments are deemed legitimate only insofar as they align with perceived divine will. Milei’s own rhetoric—branding his coalition as “Las Fuerzas del Cielo” (“the Forces of Heaven”)—signals a full-throated embrace of this apocalyptic cosmology. In such a world, elections are not mechanisms of civic accountability, but tests of spiritual allegiance.

The examples of the United States, Brazil, and South Korea demonstrate that once political movements conceive of themselves as instruments of divine will, the transition from democratic participation to authoritarian subversion can unfold with alarming speed. Theologically sanctioned power is not easily relinquished, and when prophecy is allowed to override political reality, the foundations of democratic governance begin to erode. If this theological-political synthesis continues to expand unchecked, the next attempted coup may not end in failure—it may succeed in the name of God.