In The Da Vinci Code, Silas purifies himself through self-flagellation after murdering in the name of Christianity. He strips naked to kneel in the center of his room and clamps a spiked cilice belt around his thigh. “Pain good”, he reminds himself of the words of Father Josemaría Escrivá, “the Teacher of all Teachers”.

Silas, the antagonist and one of the central figures of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, is part of a secret Christian cult called Opus Dei. But Opus Dei is not fiction. On the contrary, Brown’s book helped shine a new light on its long-hidden practices and widespread influence.

Meaning “Work of God” in Latin, Opus Dei was established in Spain in 1928, though it quickly spread across the world. It is based on the foundational idea that Christians should be given the chance to serve God in their everyday lives, carrying forward the gospel in their jobs and in society at large, without ever having to enter the nunnery or the priesthood.1

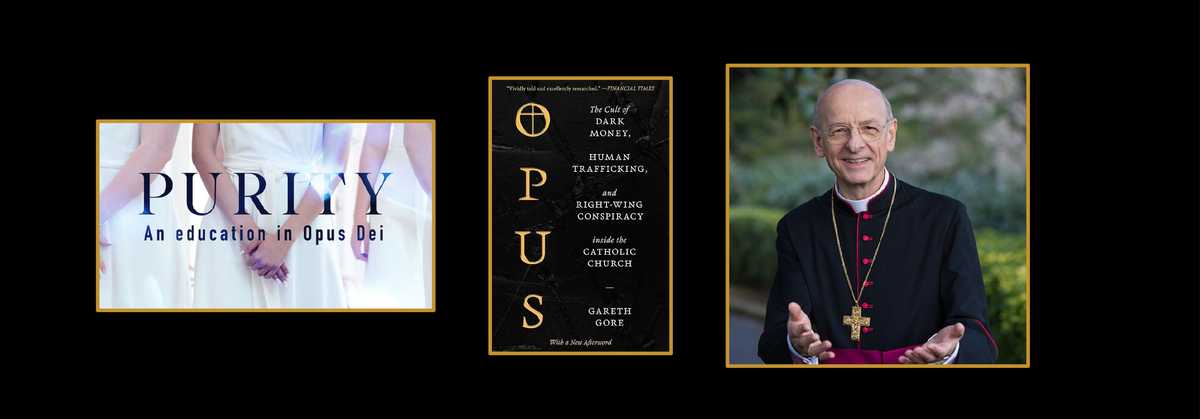

Despite the publicity of the early 2000s brought on by Da Vinci, Opus Dei has since mostly managed to avoid reigniting the type of controversy generated by the film.2 In fact, over the years, they’ve pushed back vehemently against Dan Brown’s portrayal, claiming that the version of Opus Dei in print and on-screen was highly inaccurate and fictionalized; 3 instead, they wanted to make sure the public knew the “real” Opus Dei.

According to journalist Gareth Gore – author of Opus: The Cult of Dark Money, Human Trafficking, and Right-Wing Conspiracy inside the Catholic Church – following the film’s release, Opus Dei used a combination of “shrewd communications,” interviews, “guided tours,” and a USD 1 million hush payment to turn “lemons into lemonade.” 4 Members of Opus Dei successfully portrayed criticisms of the group as anti-Catholic backlash targeting the Catholic Church itself. 5 By the end of this campaign, not only had The Da Vinci Code not led to the downfall of Opus Dei, but it actually helped propel the organization to new heights by recruiting new followers and allowing them to further conceal real crimes.6

But if Opus Dei could turn a potential PR nightmare into a new opportunity, what other potential scandals could it be keeping at bay? What else could renewed public scrutiny help bring into the light? And what would new revelations say about Opus Dei and its impact, financial and ideological, not only about the Catholic Church, but also the growing power of the global far right?

Origins

It was the collapse of a Spanish bank – named Banco Popular – in 2017 that led Gareth Gore to first investigate the organization. By 2024, he was releasing Opus, the most recent widescale exposé into the machinations and influence of Opus Dei.7

“Like everyone else,” when he first went to Spain to report on what seemed like just another bank crisis, he said, he “missed the most important part of the story:”8 Following the bank’s collapse, most shareholders, he noted, had tried to recover their money. Most, but one.9

This shareholder, known as La Sindicatura, held approximately 10% of the bank, amounting to nearly EUR 2 billion.10 Instead of trying to recoup its costs, this shareholder was working to dissolve itself and disappear. Gore quickly discovered that, behind the Syndicate, were dozens of companies and foundations. The significant dividends being earned by these organizations were being distributed through “support companies” to a network of schools, residences, and retreat centers, all leading back to one organization: Opus Dei.

In fact, at the time of the bank’s collapse, Opus Dei had been in control of the bank’s board for around two decades.11 Over the years, a range of services had been made available to it, including currency movements, shell companies, and secret accounts in Panama and Switzerland.12 The bank had also set up a charitable foundation to which 5% of its profits had been dedicated each year, amounting to USD 150 million total. The bank’s chairman, a member of the Work (Opus Dei’s members and people familiar with it often refer to it simply as the Work), Luis-Valls Taberner, insisted the money was being used for “good causes”; most of the money had gone to projects run by Opus Dei.13

To understand the ideological and structural roots of this financial entanglement, it is necessary to turn to the early life of Opus Dei’s founder, Josemaría Escrivá, and the formative experiences that shaped the organization’s foundational ethos.

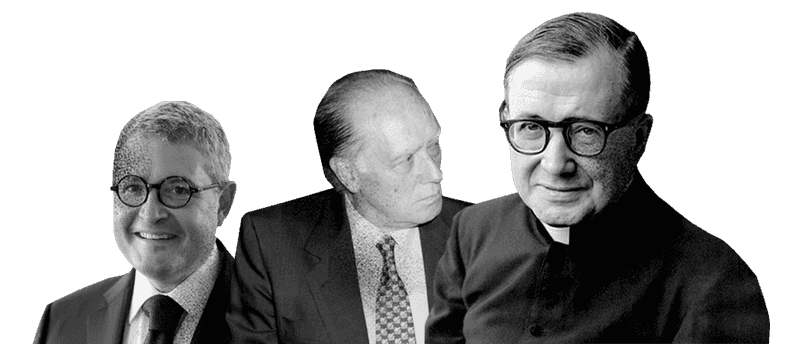

Josemaría Escrivá’s father went bankrupt when he was only 12. In search of a “better life,” Josemaría chose to enter the seminary. He also studied law and subsequently applied for the civil service, though he was unsuccessful. It was around this time, in 1928, that Escrivá began to outline the basic principles that would become Opus Dei.

At first, according to Gore’s research, Opus Dei “encompassed ideas such as compassion, forgiveness and charity.” However, it quickly evolved into something akin to a sect, as well as a lobby group.14 Escrivá began to envisage his followers as a “hidden militia” that could collect information about the “enemies of Christ” while also carrying out the “orders of Christ.”15 In 1934, Escrivá outlined aphorisms for living a more godly life in his famous Spiritual Considerations, an early version of his influential book The Way. In 1967, Time magazine said of The Way, “it might well be called How to Win Friends and Influence God.” The book had already sold over two million copies in 15 languages when Time published its review.16

According to professor of theology and religious studies Massimo Faggioli, a core tenet of Opus Dei is an opposition to the separation of church and state; they view the two, instead, as having a “symbiotic relationship.”17 Escrivá once described the organization by saying: “We are an intravenous injection, inserted into the circulatory torrent of society… to immunize the corruption of mankind and to illuminate all minds with the light of Christ.”18

However, as Escrivá sought to recruit warriors for God, Spanish society as a whole was turning in a different direction. In the 1930s and 1940s, in Spain, workers were rising, demanding new rights, including the redistribution of large estates. Many were also turning their backs on the church and questioning its role in society.19 Opus Dei, many believe, represented an attempt by more conservative thinkers within the Church to “rechristianize” Spain and wrestle it back from the country’s revolutionaries.20

Escrivá began drawing out a “deeply political, reactionary, militant manifesto.” He viewed his followers as members of a “guerrilla army” that could “infiltrate” every part of society, including the government, the judiciary, academia, journalism, and business, among others. Subsequently, the organization's religious aims quickly turned political.21

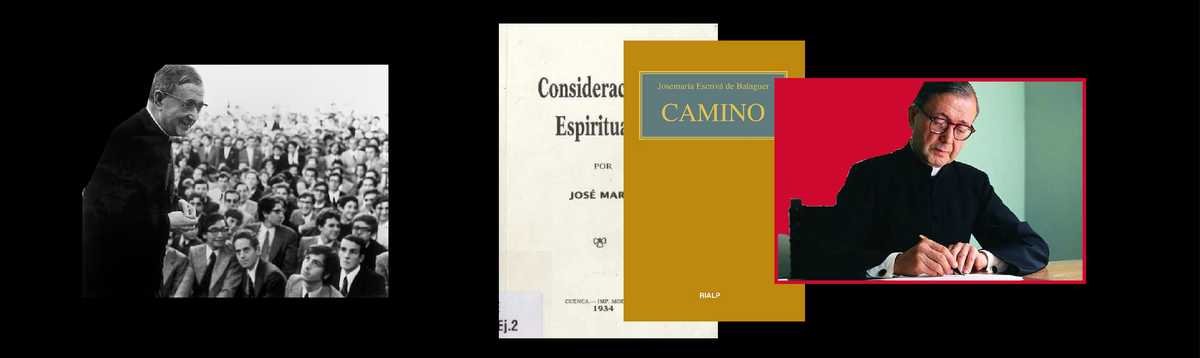

Despite Escrivá’s grand ambitions, however, the growth of the organization was impeded in its early years by the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.22 According to the work of Opus Dei-affiliated historian José Luis González Gullón, most members of Opus Dei, at the outbreak of the war, were living in the country’s “Republican zone.” They experienced anti-Catholic pushback, leading members of the organization to seek refuge. According to Gullón, between October 1936 and March 1937, four members of the organization were confined to prison and two, including Escrivá, hid momentarily inside a psychiatric sanatorium.23 Yet, following the overthrow of Spanish democracy by General Franco, Escrivá began travelling around Spain; Opus Dei spread quickly from Madrid to other Spanish cities. By the end of World War II, Opus Dei’s influence was beginning to spread far beyond Spain.24

Today, Opus Dei is composed of tens of thousands of members. Most famously, this includes supernumeraries, who comprise around 70% to 80% of Opus Dei. Often married, they participate in “normal” careers, many of them occupying the highest echelons of society. Cooperators are the ones who are not officially members but offer support of various kinds, including prayer, financial support, and sometimes professional services.25 Opus Dei’s pamphlet on cooperators describes how, for example, one former bank executive in Hong Kong was using her entrepreneurial skills to sell and distribute the books of Josemária.26 Meanwhile, numeraries are famously celibate and live in Opus Dei-run centres. A smaller number of associates are also celibate, but continue living independently or with their families.27

The final category, numerary assistants, composed exclusively of women, is responsible for domestic chores. While numeraries have careers, numerary assistants dedicate themselves entirely to serving the needs of higher-ranking Opus Dei members.27 According to the organization itself, priests are then drawn from among the flock of long-standing numeraries and associates, who have carried out the studies required of the priesthood;28 usually, these are individuals deemed by the organization to possess a similar philosophy and suitable politics.29

Flourishing Under Franco

According to Gore’s account, the post-Civil War expansion of Opus Dei could be boiled down to one name: Francisco Franco. In Gore’s words, “complicity with his bloody dictatorship was what helped them grow.”30 Indeed, the Time magazine report from 1967 noted the numerous members of Franco’s cabinet who were also Opus Dei members, including Laureano López Rodó, Minister of Development Planning; Gregorio López Bravo Castro, Minister of Industry; Mariano Navarro Rubio, Governor of the Bank of Spain; and Alberto Ullastres, Ambassador to the European Economic Community.31 Franco’s right-hand man, Admiral Carrero Blanco, is thought to have also been connected to Opus Dei and was a fierce defender of the organization within the regime.32

Franco considered Escrivá to be “very loyal” and brought about the perfect conditions for the evolution of Opus Dei by making religion classes compulsory and encouraging religious orders to create student residences where residents would be supervised in their religious studies.

In one letter dated 1952, written by the priest who would eventually replace Escrivá as leader of Opus Dei, Álvaro del Portillo, a direct request was made: Public funds for Opus Dei. In his letter, he proposes “a simple formula” for the sharing of state money with the organization “that does not represent any burden on the public treasury.”33 Del Portillo also alluded to the organization’s upcoming plans for expansion into the education sector, including the “setting up” of “some high schools, some vocational training institutes for university students and postgraduates.”34 Del Postillo asked as well that the castle of Peñíscola be granted to Opus Dei for the creation of a center of Opus Dei “high culture” for “intellectuals from all over the world.”35 Continuing to spread the gospel of Opus Dei among the “peasants and the workers,” he said, would require “sacrifices of an economic order in the service of God and the Fatherland.”36 This was necessary to ensure that the efforts of the “New State” under Franco would not succumb to “the influence of dark sects and subversive doctrines.” Subsequently, Del Potillo requested a loan of 55 million pesetas from the Bank of Spain.37

Though Franco did not approve this request, his regime had already donated 1.5 million pesetas for the Roman College of the Holy Cross, “a center of updating numerary men.” Other forms of support were less direct. For example, the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), established in 1939, was headed in part by José María Albareda. A member of Opus Dei, Albareda immediately began to divert state funds from CSIC to Opus Dei by awarding grants to members of the organization.38 By 1947, Escrivá had purchased a palace in Rome known as Villa Tevere,39 with additional constructions in the 1950s.40 The villa included 12 dining rooms and 14 chapels.41 As the 1967 Time article noted, “Franco appears to have submitted practically all of Spain’s economy to the hands of Opus Dei.”42

However, it wasn’t until Opus Dei extended its influence beyond government and into the country’s banking system, “hijacking” Banco Popular in the 1950s, that it obtained the financial power needed to take its expansion global. With the help of shell companies and flows of hidden cash, it opened residences, schools, and universities, among other initiatives.43

According to Gore, “the official archives of Banco Popular are peppered with mentions of subsidiary companies [belonging to] Opus Dei.”43 In 1955, they began the takeover of the bank by targeting financially precarious shareholders and buying them out through shell companies.44 This “hijacking” of Banco Popular by Opus Dei was complete by 1957,45 when Luis Valls-Tarberner was appointed executive vice-president,46 eventually becoming co-president for decades alongside his brother Javier. Luis, an Opus numerary, ran the bank by day, retreating at night to an Opus center where he would recreate the pain of Christ by wearing chains with spikes around his thigh. According to Gore, “Without Luis and the way in which he diverted money from the bank, Opus Dei wouldn’t be what it is today.”47 One website, paying tribute to Valls-Taverner on behalf of a group of numeraries, estimates that EUR 700 million had been contributed to Opus-related entities and projects.

Luis is not, however, the only man whose name was famously connected to both Opus Dei and Banco Popular. In 1965, Gregorio Ortego, Banco Popular’s “man in Lisbon”, was arrested in Venezuela with a suitcase full of banknotes. Ortego, it seemed, had become the main money launderer for Opus Dei. As Gore’s reporting shows, by this time, 138 “auxiliary companies” were generating money for the organization. Opus Dei had created a sophisticated system of bank accounts under the names of its trusted numeraries.48

The same 1967 Time magazine article reporting on Opus Dei’s connection to the Franco regime also claimed that, beyond “owning” Banco Popular, Opus controlled 13 other banks and insurance companies, as well as 16 real estate and construction firms, and an industrial empire, which included five chemical plants. Furthermore, the Time article claimed that two Madrid newspapers were owned and edited by members of Opus Dei, as well as a dozen Spanish magazines and publishing houses.

Finally, according to Time, three members of Opus Dei were sitting on the privy council of Don Juan de Borbón y Battenberg, the pretender of the Spanish throne, while an Opus Dei priest was serving as confessor to then Prince, now King, Juan Carlos, of Spain. The article noted that, in Colombia, two leading candidates for president had been Opus Dei supporters. The same was true of UK Tory MP John Biggs-Davison and the Queen Mother, the latter having presided over a dedication to the organization at London’s residence hall in 1966, not long before the article was written.49

By 1969, as more businessmen joined the ranks of Opus Dei, the organization became embroiled in the Matesa scandal. One of the biggest financial outrages to hit the Franco regime, the scandal led to the head of textile enterprise Matesa, Juan Vilá Reyes, being convicted of “irregular business deals” and exploiting a government policy designed to boost Spanish exports. 50 Reyes had been educated in an Opus Dei business school and was assisted by the Governor of the Bank of Spain, Mariano Navarro Rubio, in his illegal dealings.51 Over the course of these “irregular business deals,” millions of dollars flooded into Opus Dei accounts.52

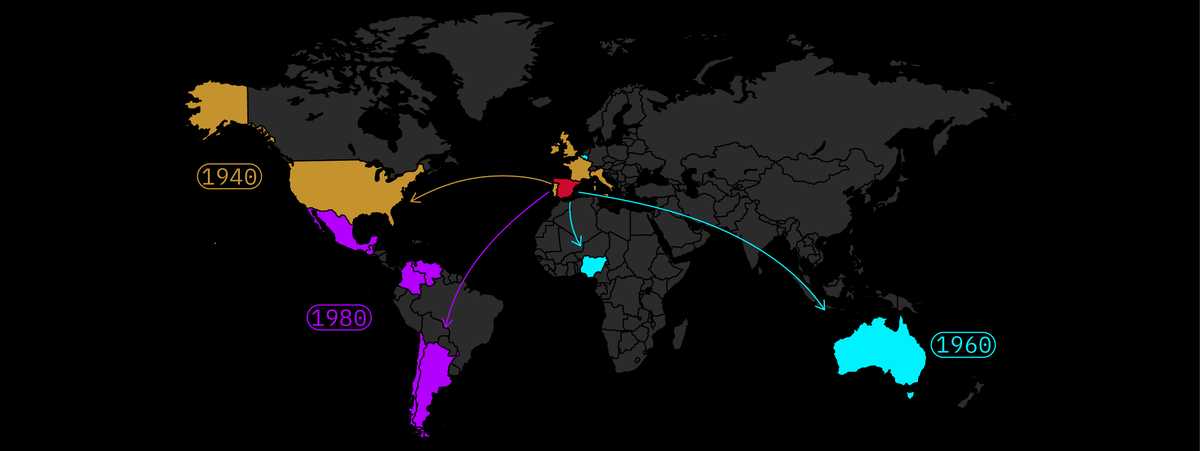

Following the end of the Civil War and World War II, and with increasing funds, Opus Dei began its global expansion. The organization expanded first across Europe, to Portugal, England, Italy, France, and Ireland, as well as to the United States – all by the end of the 1940s. By the 1960s, its expansion included Australia, Nigeria, and Belgium. Opus Dei expanded throughout Latin America in the ensuing two decades, where it would hold great power – first in Mexico, then in Chile and Argentina, followed by Colombia, Venezuela, and Guatemala.53

The Vatican Connection

Opus Dei’s influence within the Vatican expanded significantly under Pope John Paul II, a staunch conservative who strongly approved of Opus Dei’s opposition to sexual freedoms and promotion of “traditional” values.54

In 1950, Opus Dei was officially approved by the Holy See as a “secular institute,” whose members “profess the evangelical counsels in secular life.”55 However, its elevation, on November 28, 1982, to “personal prelature” by Pope John Paul II conferred on the organization a new, and previously unheard of, level of power within the Catholic Church.56 A “personal prelature” refers to a group that carries out “pastoral activities” and falls under the supervision of the Vatican’s Congregation for Bishops.57 Although the Catholic Church created a new category within its Canon Law, the official law of the Catholic Church, with "personal prelatures", Opus Dei is the only organization that has ever been given this status.

Members of Opus Dei had long argued that existing structures within the Code of Canon Law had so far been “inadequate” in truly reflecting the unique nature of Opus Dei.58 Since 1982, both clergy and laypeople within the Work have been governed by a prelate, elected by an “executive congress,” who holds lifetime office.59 The first prelate was Escrivá himself, followed by right-hand man Alvaro del Portillo.60

According to Jesuit Fr. James Martin, a critic of Opus Dei, the “personal prelature” designation has allowed Opus Dei to go about “almost untouched by criticism or oversight by bishops.”61 It meant that Opus would no longer be accountable to local bishops, who would not have the same authority over Opus as they did over other orders or groups under their dioceses. Quoting scripture, Martin said Opus Dei had become “a people set apart.”62

Opus Dei members’ status thus rose quickly within the Vatican, where they became a main fixture. Among other such examples, Opus member Joaquín Navarro-Valls became director of the press office at the Holy See in 1984, a position he held for more than 20 years. During his tenure, the Vatican began using the media to more strongly promote a conservative worldview. On May 28, 1989, a conservative Mexican newspaper called El Heraldo announced that 24 Opus Dei members, from the U.S. and across Latin America, had been ordained by Pope John Paul II in Rome. Finally, in 2002, John Paul II canonized Opus Dei founder Josemaría Escrivá, also in Rome.63 Therefore, John Paul II played an essential role in turning Opus Dei into what it is today – a group made up of over 90,000 members spanning 70 countries globally.64

John Paul II’s support for Opus Dei came as part of a larger effort to consolidate conservatism within the Church. It also sought to counteract the expansion of a progressive religious movement known as Liberation Theology, which was then spreading throughout Latin America, as part of a growing opposition movement against the continent’s U.S.-imposed far-right dictatorships.

Some clerics within the Latin American Episcopal Conference (CELAM) believed at the time that they could counteract Liberation Theology by hiring Opus bishops. According to Argentine-Mexican academic Enrique Dussel, Lopez Trujillo, secretary of CELAM, also worked directly with Opus Dei as part of an anti-Liberation campaign. The group even took part in the Los Andes meeting in Chile in 1985. This meeting resulted in the Andes Statement, which denounced Liberation Theology as a “Marxist perversion of the faith.” 65

A Global Network

Today, Opus Dei continues to infiltrate elite circles globally, anywhere where it can attempt to exert ideological control; this includes through its system of schools and universities, designed to train an elite ready to reproduce the organization’s ideological leanings. Indeed, many prominent activists opposing reproductive rights and state secularism across the world have graduated from Opus schools.66 Journalist Gareth Gore has suggested that Opus Dei be considered not a religious organization, but rather “a network of like-minded archconservative radicals who in many instances use the beliefs to push forward a deeply political agenda.”67

According to Gore, Opus Dei today operates hundreds of “arm’s-length nonprofits, foundations, and charities, which officially have nothing to do with the organization, but which in reality have everything to do with the organization.”68 Opus Dei makes important decisions on behalf of these organizations and even decides who sits on their boards. In the U.S., Gore has identified close to 100 relevant foundations worth around one billion dollars, which are used to fund Opus Dei residences and sometimes even political initiatives. Gore’s research has linked foundations to campaign and lobbying efforts in the U.S. dating as far back as the 1990s.69 70

Opus Dei’s “corporate works” also include its London headquarters, owned by Netherhall Educational Association, whose trustees are all members of Opus Dei. These headquarters consist of a row of GBP 5 million townhouses near Kensington Palace. Likewise, Murray Hill Place, the organization’s U.S. headquarters, is owned by a non-profit of that same name, and is worth USD 69 million, paid for in part from pharmaceutical stocks donated to Opus Dei. Accounts of the seven charities that own the main Opus Dei centres in the UK declare assets worth GBP 65 million.71

While Opus Dei has successfully infiltrated the elite of many countries, the way it wields this power in Mexico, the country with the most Opus Dei members outside of Spain, is informative. In Mexico, it has been common for politicians and bureaucrats from the conservative Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) to have been educated at Opus Dei schools; indeed, this was the case for PAN leader César Nava Vázquez. Another important member of PAN was Paz Gutiérrez Cortina, a columnist as well as an Opus Dei supernumerary. She was also the national director of Enlace, which has collaborated with the anti-choice organization Provida as well as conservative groups like Red Familia,72 which claims to defend the “traditional family.” In 2018, Enlace signed an agreement with the Ministry of Education in Guatemala to provide scholarships and diploma courses for public school teachers.73 This training reportedly denied sexual diversity and reproductive autonomy, as well as vilifying divorce and contraceptives, including condoms, as an evil “imposed by gender ideology.”74

Other leading public figures who have been tied to Opus Dei include Carlos Llano Cifuentes, the founder of Instituto Panamericano de Alto Direccíon de Impresas (IPADE Business School), who reportedly exerted a strong influence on right-wing officials, such as former Secretary for Social Development and Education Josefina Vásquez Mota.

Across Latin America, Opus Dei has been connected to conservative forces and the education of key right-wing figures. Notably, in the 2000s, figures tied to Opus Dei were also tied to two right-wing coups in both Venezuela in 2002 and Honduras in 2009.75 According to U.S. intelligence firm Stratfor, the CIA had advanced knowledge of the coup plans in Venezuela and may have even supported some of the figures linked to the coup; they are said to have met with relevant figures that included “militants from Opus Dei.”76 Following the coup, the new government was installed almost immediately, as foreign minister Jose Rodriguez Iturbe, a member of Opus Dei.77 In Honduras, the Opus Dei-linked church was reportedly involved in the coup, with the goal of furthering their control over “family planning.”78 After the coup, the former Women’s Minister was forced into hiding and replaced by Maria Martha Diaz, a member of Opus Dei, who promised to halt progress on sexual and reproductive rights.79

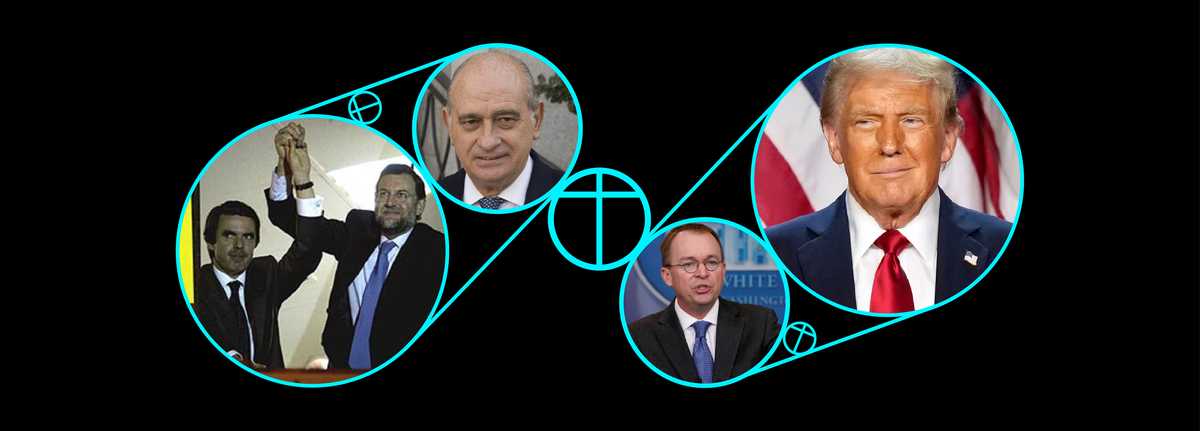

Though Opus Dei’s power was, and continues to be, particularly influential in Latin America, this was not the only region in which it was making waves during the 2000s.80 In Australia in 2005, New South Wales Liberal Party Legislative Council member David Clarke shared that he was a “cooperator of Opus Dei.” In his first speech to the Council, he promised to advocate for his Christian ideals with a “missionary zeal.” It was soon reported that those in his party who didn’t “ascribe to the program” were being pushed out of the party by Clarke and other arch-conservatives.81 By the beginning of the 2010s, Opus Dei was said to be popular as well in Germany’s financial capital, Frankfurt.82 A 2011 article from Der Spiegel noted that, “There is hardly a German bishop who does not regard the organization, founded in Spain, with favor.”83 Opus Dei continued to maintain a powerful position in Spain as well. Three ministers in the Popular Party government of José María Aznar, who ruled between 1996 and 2004, belonged to Opus Dei, while the Interior Minister to former Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, Jorge Fernández Díaz, also belonged to the organization.84

Of course, in the U.S., Washington, D.C.’s political elite has long been tied to Opus Dei.85 In 2001, spy and Opus Dei member, Robert Hanssen, was arrested after it was discovered that he had been secretly spying for Russia.86 As it turned out, not only had Opus Dei known, but an Opus Dei clergyman, who heard his confession of guilt in 1981, had suggested that, rather than turn himself in, he turn the money he had received over to Opus Dei instead.87 As early as the late 1980s, former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia is said to have been a regular at Opus Dei retreats. Today, many members of Trump’s current and former staff and entourage are notably also members, or strongly affiliated, with Opus Dei, 88 including Mick Mulvaney, chief of staff during the first Trump administration.

Recruitment & Infiltration

One key question that has long surrounded Opus Dei is how it has been so successful in recruiting so many powerful individuals to its ranks. And one important answer lies, of course, in the organization’s expansive focus on educating university elites, including future business executives, as well as influencing children from a young age through a slew of elementary and high schools which it owns and/or operates.89

As recently as 2024, 100,000 kids and college-age students were passing through educational facilities linked to Opus Dei on a daily basis.90 By 2011, Opus Dei counted 64 residences in 17 U.S. cities alone.91 According to Opus Dei’s own website, 19 universities, serving approximately 117,000 students, currently have “spiritual care” agreements with the organization. The Opus Dei universities with the largest number of students are Universidad de la Sabana in Colombia, Universidad Panamericana in Mexico, and Universidad de Navarra in Spain.

However, the full list of universities connected to Opus Dei today spans Africa, South America, Asia, and Europe. The organization itself additionally claims that there are currently 12 business schools with which they have “agreements” to provide “pastoral care and Christian orientation.” Opus Dei further makes note of 275 primary and secondary schools globally with such agreements, 70 of which have a “general agreement for Christian education”; others have “more limited agreements for pastoral care.” With respect to student residences, Opus Dei acknowledges that there are currently 228 globally, housing 5,800 students. Finally, Opus Dei claims to have agreements with 160 vocational schools.92

Opus Dei’s educational impact is perhaps best exemplified by its power within the Spanish school system, beginning with elementary and secondary schools, notable examples of which are Tajamar and Los Tilos in Madrid. Despite a national ban on gender segregation for publicly funded schools in Spain, the president of the Community of Madrid, Isabel Díaz Ayuso, granted an extension to implementing the relevant law, with boys continuing to attend Tajamar while girls attend Los Tilos. These two schools receive, nonetheless, a great deal of funding from the regional government: Tajamar received EUR 5.6 million during the 2020/2021 academic year, with the private company that administers the school receiving an additional EUR 860,000. Meanwhile, the school reportedly received EUR 4 million from fees paid by students, despite the school’s public funding.

Spanish writer José Ovejero was one of the many students who passed through the halls of Tajamar in the late 1960s. He has recalled Opus Dei’s attempts to recruit him, and indeed their success in doing so with several of his classmates. Among other things, he recalled attending camps where women weren’t allowed to speak and could only serve food. Meanwhile, Escrivá, he said, could be seen arriving at the school in a Mercedes. He has also spoken out about the pernicious impact of Opus Dei on his views and feelings around sexuality. This is something that has also been echoed recently by Spanish public figures, including comedian and writer Victoria Martín, as well as filmmaker Javier Ambrossi, who said Opus humiliated him for being gay. In addition to Tajamar and Los Tilos, there are reportedly a dozen more schools connected to Opus Dei in Madrid. This includes Retamar, which received EUR 14 million in income during the 2021/2022 academic year and was attended by current Madrid Mayor José Luis Martínez-Almeida.

In Spain, Opus Dei is also linked to four important business groups that each run a number of schools. One of these groups, Attendis, oversees 20 schools and 13 private early childhood education centers. With 11,000 students overall, it describes itself as “the largest private education institution in southern Spain.” According to its 2021/2022 financial statements, the group generated over EUR 56 million, including profits above EUR 1.6 million. It also owns 23 properties with a combined value of more than EUR 70 million. On their website, Attendis explains that they promote the teachings of Escrivá about “family, a love of work well done and concern for others.” The secretary of Attendis’s board of directors, Alberto Tarif, also currently serves as director of communications for Opus Dei in the city of Granada.

Also notable is Opus Dei’s role as the founder of the Universidad de Navarra in the 1950s. Today, the university serves more than 15,000 students and is considered Opus Dei’s most prestigious institute of higher education within Spain. Although Navarra is legally part of the Catholic Church, it’s effectively governed by Opus Dei. The current prelate, Fernando Ocáriz, is also the university’s Grand Chancellor. Despite being a nonprofit, the university reported a profit of nearly EUR 25 million in 2022/2023. It invested approximately EUR 32 million into its Instituto de Estudios Superiores de la Empresa (IESE) business school campuses in Madrid and Barcelona.

IESE, which is part of Navarra, is one of the country’s most prestigious business schools. According to a 2018 investigation by media outlet La Marea, one in six executives at Spain’s top 35 companies studied at IESE. The institution is also a favoured choice for board members at Spanish multinationals. Though Opus Dei is said by some to have lost public visibility in Spain, their educational affiliations allow it to maintain an important source of power within the country.93

Spain is not the only country, however, in which Opus Dei utilizes the educational system to reach students who may one day possess enough power to bring their ideas forward. In the U.S., for example, where Opus Dei’s influence is still growing, its educational focus has been centered around D.C. prep schools and Ivy League institutions. The Heights School in Washington, D.C., is an all-boys’ school affiliated with Opus Dei. Though it’s less well known than some of the most famous D.C. schools like Sidwell Friends, The Heights became popular among a small group of important conservative Catholics. Among those who have studied there are the children of former Senator Rick Santorum, former US Secretary of Defence Chuck Hagel, and former FBI Director Louis J. Freeh. All-male faculty members teach at the school and adhere to Catholic teachings. Employees at the school have included members of Opus Dei, which provides the school with “spiritual formation.” Opus Dei appoints the school’s chaplain, the school provides daily mass, and faculty are encouraged to integrate the “traditional reading of Catholicism” into their teaching.94

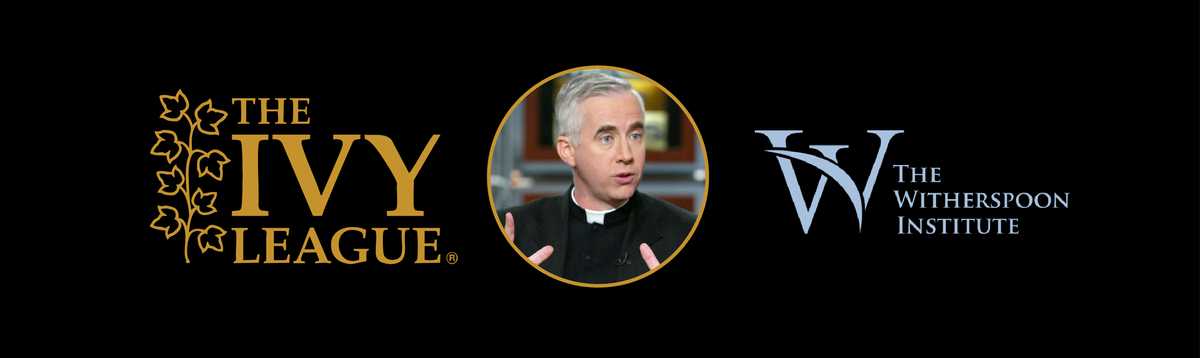

Various initiatives within the American Ivy League have also been the recipients of Opus Dei’s educational largesse. At Princeton, the university’s James Madison Program on American Ideals and Institutions has received hundreds of thousands of dollars from organizations connected to Opus Dei. Money has gone to other initiatives at the university as well, including Princeton’s Council of the Humanities.95

One figure involved in the Ivy League from early on was Father C. John McCloskey, a well-known Opus Dei priest and former Wall Street Banker.96 He was, however, removed from his position as associate chaplain of Princeton’s Catholic Aquinas Institute in 1990, following accusations of overly aggressive recruitment efforts at the university, as well as impinging on academic freedom by opposing anti-Christian books.97 It was alleged that McCloskey asked students embarrassing and explicit questions and would advise students not to take classes with certain “dangerous” professors or read philosophers, including Nietzsche.98

A second important figure, still active today, is Luis Tellez, a prominent Opus Dei figure within the U.S. He is a member of the Advisory Council of the James Madison Program and has held the position of director of Opus Dei at Princeton. He also serves as president of a conservative think tank called the Witherspoon Institute,99 which is a strong opponent of same-sex marriage; its work has been cited by Republican members of Congress. Tellez is also a founder of the National Organization for Marriage, which has opposed the legalization of same-sex marriage.

According to Gareth Gore, Tellez left St. Louis in 1981, where he had directed a numerary residence. He was one of the minds that first conceived of the James Madison Program, founded in 2000 with money from the Clover Foundation and from the conservative John M. Olin Foundation.100

Beginning in the 2000s, the James Madison program started hosting dinners, lectures, and talks by prominent conservatives, including then Supreme Court Justice Anthony Scalia and former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. In the first half of the 2000s, organizations affiliated with Tellez and Opus Dei contributed USD 500,000 to both university professors and programs, most of which went to the Madison Program.101 102

Numeraries: A Life of Servitude

Around the world, a majority of Opus Dei members are lay people, known as supernumeraries. While supernumeraries hand over about 10% of their salaries to Opus Dei, celibate members are expected to be fully devoted to the Work.103 Conditions for numeraries include adhering to rigid rules with respect to almost every aspect of their daily lives, from how they communicate with others to how they spend each moment of their time and money.104 Numeraries are even taught to snitch on each other should anyone among them stray from these principles.105

The practices historically expected of numeraries include, now famously, mortification, such as tying a chain cilice, which is a spiked belt, two hours per day across one’s thighs. Other smaller forms of mortification may have included sitting in an uncomfortable position or denying oneself food.106 Numeraries were also expected to sleep once a week on a wooden board, with women expected to do so every night. On Saturdays, members would strike a cord-lick whip over their shoulders while praying to the Virgin Mary. Articles would also be cut out of newspapers, while a book rating system determined what books residents were allowed to read. While Gore has reported that the Vatican abolished a system of book indexing in the 1960s, Opus Dei seemingly maintains one of their own.107

Other controls on the lives of numeraries are reported to have included: being barred from holding a bank account, having mail read by directors before being able to access it, having to notify directors of all comings and goings, and being barred from attending non-Opus Dei events. Reports have also indicated that Opus Dei may teach recruits to leave parents and other family members out of decision-making by telling them that “they will not understand.”108

In fact, Escrivá himself left behind hundreds of pages detailing how the numerary lives were to be regulated.109 When numeraries join Opus Dei, they commit to living according to “the spirit of Opus Dei” and to obey their directors.110 Numeraries are also tasked with providing “spiritual guidance” to Opus Dei members, as well as, most crucially, recruiting new members.111 Should they decide to leave, they are told, they will do so without God’s grace and may be damned for eternity.112

These conditions are known to perpetuate mental distress among numeraries and assistants. And yet, when such issues arise, they are only allowed to consult professionals within Opus Dei itself, who are often more concerned about keeping them within the organization than in truly providing the necessary help.113

While Opus Dei notably courts those likely to occupy the future and current halls of power, their ability to do so convincingly has remained contingent on one central, yet overlooked, role in Opus Dei: that of the assistant numerary. This role is made up of rural and poor women from around the world, recruited into lives of “indentured servitude.”114 Once recruited, they are forced to devote countless hours of labor each day, as they ensure Opus Dei’s influential members across the globe receive the best possible hospitality at Opus centers.115

Today, there are about 4000 numerary assistants globally.116 Officially, their role is to create “the atmosphere of a Christian home.” However, what Opus Dei describes as “mothers or sisters working in their own home,” 117 others have described as harsh labour conditions:118 spending up to 12 hours – some reports even claim 15 – a day cooking, cleaning, as well as doing laundry and other chores.119 They take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience; they remain unpaid, receive no actual labour contract or retirement account.120 Furthermore, there have been reports of manipulation and pressure wielded against women who have tried to leave. Some have referred to their conditions as akin to “modern slavery.” Although Opus has argued that assistant numeraries no longer experience inferior living conditions, a report from the Financial Times has found that, while in the UK assistant numeraries have access to studies, cars, and social media, in many lower-income countries, “effective caste systems still persist.”121

To ensure a continued supply of such assistants, behind the facade of elite Opus Dei schools and universities lies a much more nefarious schooling system: the Opus Dei “hospitality” schools.

According to journalist Gareth Gore, money from Banco Popular was used to set up a network of such schools to recruit girls as young as 12 or 13.122 They are then lured with promises of a better life through education in the hospitality and hotel management sector. Women have claimed, however, that when they arrived at these schools, they were immediately put to work. They were told to remain obedient and to share nothing with their parents. After some years of “schooling,” women claim they were forced into becoming official numerary assistants.123

According to Opus Dei’s website, the organization began its foray into higher education in the 1960s, which it says included hospitality schools;124 one of the earliest was what eventually became known as the Kibondeni School of Institutional Management in Kenya.125 As Opus Dei itself has stated, the first assistant numeraries in Kenya were indeed recruited from that school.126

More than a decade later, in 1973, one of the now more infamous Opus Dei “vocational” institutions was opened on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, Argentina: the Instituto de Capacitación Integral en Estudios Domésticos, ICIED.127

In 1979, ICIED’s first director, Ana María Sanguinetti, sought to expand the school further, as women were needed who could perform chores for the growing ranks of elite Opus members passing through the centre. Along with other women, she put together lists with the names of 12 and 13-year-old girls who would be good candidates; they were poor, lived in rural areas, and had no chance at an education – they were also Catholic.127 Many supernumeraries found the names of possible recruits from people they already knew, including family and friends.128 Quickly, the news spread: A free school had been set up in Buenos Aires that could teach young women to become professional maids.

Women who attended the school have reported spending from dawn until dusk tidying up, cleaning, and cooking, both for themselves and for the Opus Dei guests, with only a short space for classes in the afternoon. Women and men staying at the centre, known as La Chacra (meaning “The Farm”), were never supposed to see each other. Specific techniques were required for everything from stocking the pantry to making the beds. Though there was a telephone on which the girls could receive calls, many of their families didn’t have the means to reach them. If they did, the call might not even go through. Meanwhile, letters went straight to the director’s office, where a numerary would check them over before sharing them. If someone died in one of their families, the letter announcing the death would not be handed over for a full month, to ensure that relevant gatherings would already be over.129

One Irish woman who attended an Opus Dei school known as Crannton in the late 1970s recalled playing “YMCA” on a record player only to have one of the directors storm in and break the disk over her knee. Another woman from a different Irish vocational school, Lismullin, remembered being told she would go to hell if she continued asking where the money from well-heeled Opus Dei members was going, while the soles of her own shoes were falling off.130

Many women who attended vocational schools have claimed they were given no real choice in whether to become permanent numerary assistants.131 Women were told that if they didn’t follow the vocation, they and their families would go to hell.132 Once they joined, they would be separated from the rest of the girls in order to ensure that they would start abiding by additional rules, such as prayers, conversations with the “spiritual director,” confessions, theoretical training, and mortifications.133

As part of his research on Opus Dei, Gore himself spoke to many dozens of women, and their experiences were all similar. Though Argentina’s experience has become more widely known due to recent legal battles,134 dozens of other schools have been uncovered across Europe, the U.S., Africa, and Latin America, in countries including the Philippines, Ireland, Nigeria, and Belgium135 – all set up to recruit girls from impoverished families into eventual lives as Opus Dei numerary assistants.136

Opus Dei Goes to Washington

Today, Opus Dei counts over 90,000 members worldwide - 57% of whom are women – comprising a vast network of political allies, journalists, and businesspeople,137 many of whom share the goal of cultural domination of values associated with Opus Dei.138 However, it is within the U.S. where, as Gore has written, “almost a century after its founding, Opus Dei [has] come full circle…fuelling deep divisions that risk ripping our society apart.” 139

While some have argued that the influence of Opus Dei is declining in some corners, this is not the case in the United States, where there has been a resurgence in a movement for “traditional” values with the rise of two subsequent Trump administrations.140 This is particularly true in one very important place.141 Washington, D.C., according to Gore, presenting itself as a “champion for disgruntled American Catholic billionaires,” has “‘offered Opus Dei a new lease on life.’”142

Although the resurgence is recent, the roots of Opus Dei in the U.S. date far back: The first members of Opus Dei to come to the U.S. were Fr. Joseph Musquiz, along with a young physicist named Salvador Ferigle, both sent by Escrivá himself. They eventually opened a student residence called Woodlawn Residence, near the University of Chicago. In 1950, the first women of Opus Dei arrived, opening the Kenwood Residence, also in Chicago. Opus Dei soon began spreading throughout the country, including through its network of residences and university-affiliated organizations.143 As early as the late 1980s, prominent American members of Opus Dei included Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who is thought to have attended regular Opus Dei retreats outside Washington, D.C. 144

The continued explosion of Opus Dei in the late 1990s among the country’s elite came, however, in large part thanks to the power and influence of one key figure: Father C. John McCloskey, the Opus Dei priest once thrown out of Princeton (as noted above), but known in DC as the “convert maker.” 145

Following his time at Princeton, McCloskey became director of the Catholic Information Centre (CIC), between 1998 and 2004.146 There, he prepared key conservative figures for conversion, including former Governor of Kansas Sam Brownback; Supreme Court nominee Robert H. Bork; columnists Lawrence Kudlow and the late Robert Novak; and anti-abortion activists Bernard Nathanson,147 as well as former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, among others.148 Former senator Rick Santorum’s son was even baptized by McCloskey.149

According to journalist Mark Oppenheimer, McCloskey was a “devout free-marketeer,” who argued frequently for the compatibility of his political ideology with Catholic theology. According to Lawrence Kudlow, “Once Father John gets his claws into you, he never lets go.” 150

In 2019, it became known that Opus Dei had paid a close to USD 1 million settlement to a woman who accused Father McCloskey of sexual misconduct, an allegation stemming from 2002 when he was serving as director of the CIC. 151 Opus Dei shared that, after finding the complaint credible in 2003, McCloskey had been removed from his position.152 The payoff was not publicly known, however, until 14 years later, when the woman finally chose to tell the reporter her story, after which two other women came forward.

While there are currently around 3000 Opus Dei members in the United States, 800 of these are to be found in Washington, D.C., not historically a Catholic epicenter in the U.S.153 The current head of the Conference of Catholic Bishops in the U.S. is a member of Opus Dei, which has meant an increase in anti-abortion militancy and less emphasis on poverty. 154

Among Opus Dei’s adherents today is Leonard Leo, the mastermind behind the radical conservative and Catholic takeover of the U.S. Supreme Court, who is a director at the CIC. He follows in the footsteps of former Attorney General Bill Barr,155 who was also on the board of directors, and former White House counsel Pat Cipollone, who defended Trump during his impeachment trial.156 Meanwhile, Fox News Host Laura Ingraham has credited Cipollone with her conversion.157 Kevin Roberts, chief architect of the now infamous Project 2025 and president of the Heritage Foundation, is reportedly a regular at CIC, where he receives his spiritual guidance from an Opus Dei priest.

In his speeches, Roberts has remarked upon the inspiration he draws from Escrivá;158 he has also spoken at the CIC about his strategy for achieving extreme political goals through “radical incrementalism.” Notably, Roberts has also called himself “good friends” with Vice President JD Vance.159 Vance himself is said to have been converted to conservative Catholicism thanks to clergy connected to Opus Dei.160 Finally, Mick Mulvaney, who served as a Trump chief of staff during the first administration, is also an Opus Dei member.161 A ProPublica report from 2017 revealed that Opus Dei had visited Mulvaney, among a slew of other lobbyists.162

Opus Dei is also strongly represented on the Supreme Court, with Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, as well as the late Antonin Scalia, all having connections to the organization.163 Ginni Thomas, wife of Clarence, converted to Catholicism in 2002, after Leonard Leo assisted her husband through sexual harassment accusations and a hearing; she credited the Opus Dei-affiliated Scalias with bringing her husband Thomas back into the church.164

Opus Dei has often activated this network of powerful adherents to force forward their policy agenda in the U.S. This has included the 2008 push for California’s Prop 8, opposing gay marriage, which was backed by funding from Opus Dei. In fact, Princeton’s Luis Tellez struck up an alliance with the Mormon church to help ensure the passage of this legislation.165

In 2016, the Judicial Crisis Network, which campaigned adamantly against then-President Obama’s Supreme Court pick Merrick Garland,166 was also funded by dark money vehicles, one of which was run by a supernumerary couple with close ties to Leonard Leo. According to Gareth Gore’s reporting, the idea for the Judicial Crisis Network itself was conceived during a dinner between Leo and this same couple.167 It was Leo who devised the idea of taking a Supreme Court seat away from the Democrats, selling the idea to then Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.168 Leo was also the force behind dark money-funded efforts to install the three Trump-appointed Supreme Court justices.169

According to Matthew Fox, a former priest, members of the FBI, CIA, and ranking Army commanders are all part of Opus Dei. This has included members of the Joint Special Operations Command, responsible for the assassination of Osama Bin Laden, such as Gen. Stanley McChrystal. These figures reportedly “see themselves as protecting [Christians] from the Muslims”; according to investigative reporter Seymour Hersh, they have even developed insignias representative of their belief in a culture war between religions.170 Today, CIC board chairman Brian Svoboda is also a partner at Perkins Coie, an influential law firm. Affiliates of Opus Dei sit on the board of the Bradley Foundation, which is pouring money into right-wing causes and figures. This included late conservative activist Charlie Kirk.171 According to Gareth Gore, “Not since the Franco regime had the movement had such direct access to political power” as it does under the Trump administration.172

Conclusion

In fall 2022, while Trump was getting ready to announce a second run for president,173 bringing many Opus Dei-affiliated values back to the White House, a complaint was being filed in Argentina with the Specialized Prosecutor’s Office for Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons,174 on behalf of a number of women, all former assistant numeraries.175 Two years later, in September 2024, Argentine prosecutors moved to indict Opus Dei, with prosecutors accusing the organization of human trafficking and labour exploitation of girls, between 1972 and 2015.176 This was the country where, according to the previously mentioned 1967 Times article, Opus Dei had long been known as the “holy mafia.”177

This was the first time an organization part of the Catholic Church has confronted such major accusations in the court system. It’s also the first time the Catholic Church has been accused of human trafficking and the first mass complaint against Opus Dei.178 The accused include three regional vicars, which is the highest regional authority, as well as the regional secretary in charge of Opus Dei’s female section.179

According to Argentinian investigative journalist Paula Bistagnino, who has reported on the case, many women associated with the case have since been contacted by Opus Dei, which has discouraged them from continuing with their complaints. Bistagnino hopes that the judicial case against Opus Dei will continue growing across the region and beyond. “It may seem like a small group in Argentina doing this,” she says, “but it was part of a systematic working matrix by the organization across the world.”

In 2021, these women had made their case directly to Pope Francis. The Vatican, however, did not take any direct measures. Yet the late Pope Francis was still seen as considerably less friendly to Opus Dei than his predecessors. He made modest moves to limit the authority of Opus Dei, including revoking some of their special rights.180 Since 2022, their prelate no longer holds the title of bishop. These changes, along with revisions to the Code on Canon Law, reassigned jurisdiction over personal prelature to the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Clergy,181 further reducing the group’s autonomy. In Gore’s view, Opus Dei had been ignoring Francis’s “delicate” push for reform,182 as the organization insisted that the changes did not actually revoke any special rights, though Opus Dei did acknowledge a “reorganization.”183

In 2024, Gore told El País that he nonetheless saw a “fierce fight” brewing between “Opus Dei and the progressive forces within the Church.” However, he noted that, “Everything depends on how long Francis lives.”184 In May 2025, shortly after Pope Francis’s passing, The Guardian reported that the new pope had, in a “nod to tradition,” chosen to dedicate one of his first audiences, his first Sunday Blessing, to the head of Opus Dei. Observers have noted that Leo is more conservative than Francis, and at least somewhat less likely to openly chastise the American right; simultaneously, many say they expect him to also adhere to the vision set forth by Pope Francis.185 (Pope Leo, however, did face backlash from the right in October 2025 when he said it was “not really pro-life” to support the death penalty or the “inhumane treatment of immigrants.”)186 In mid-May 2025, Pope Leo XIV met with the personal prelature Ocáriz about the revisions that had been underway. According to Opus Dei’s communications following the meeting, “the pope expressed his closeness and affection” for the group, though few other details are known.187

Despite some minor setbacks, Opus Dei retains a great deal of power in many of the spheres in which it has historically exerted influence. In Spain, many members of far-right nationalist Vox are said to be connected to Opus Dei. Vox parliamentarian Lourdes Méndez-Monasterio from Murcia is a member.188 Vox MEP, “chief ideologue,” and campaign architect Jorge Buxadé, a figure of the “national-Catholic” wing of the party,189 and Rodrigo Jiménez Revuelta, the Treasurer of Vox in Segovia, have also been linked to the group.190

According to Xavier Bonal, a professor of sociology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, institutions like IESE continue to operate as instruments of class, ideological, and economic reproduction; an MBA at IESE costs EUR 82,000. María Fernández Mellizo-Soto, professor of Sociology at Complutense University of Madrid, has further argued that the goals of these schools are to shape the minds of students and instil a certain worldview, which they can carry forward both personally and professionally. She sees Opus Dei operating as a sort of “family” where members help each other reach top positions.191 In 2024, Interior Minister Fernando Grande-Marlaska was on the receiving end of homophobic insults from students at the University of Navarra after participating in a conference there. Among other things, the Minister later spoke in defence of secular education.192

Meanwhile, key Project 2025 figures are connected to Opus Dei in the U.S.; Leonard Leo is a director at Opus Dei in Washington, and Kevin Roberts, the Project's chief architect, regularly attends the Catholic Information Center run by Opus Dei.193

In October 2022, shortly after the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade, CIC honoured Leo at a fundraising dinner, where Clarence Thomas called Leo “the No. 3 most powerful person in the world.” In 2021, Leo’s power grew further when he received a windfall – an electronics business signed over to Leo from a Chicago billionaire in the form of a trust, which has led to Leo receiving USD 200 million annually. He’s since promised USD 1 billion in dark money to “crush liberal dominance.” It is thought that networks connected to Leo were responsible for donating USD 50 million to Project 2025. Allegations have since arisen against Leonard Leo of self-dealing and personal enrichment, which the Washington, D.C., attorney general is currently investigating.194 Leo has not so far cooperated.195

Meanwhile, Luis Tellez is still working to expand Opus Dei’s presence across Ivy League universities in the U.S., to inspire the next generation of Opus Dei leadership.196 Luis Tellez is president not only of the Witherspoon Institute, but also of the Foundation for Excellence in Higher Education (FEHE), which boasts of its role as a grantmaking organization for elite universities, including Princeton – as well as Columbia, Harvard, Duke, Stanford, and Yale. According to its website, it supports a total of 27 institutes or programs. It also supports a network of institutes and programs based on or near some of these top university campuses. Programs founded by FEHE, whose officers are notably paid through the Witherspoon Institute, include the James Madison Program.

Previous donors to FEHE include the Bradley Impact Fund, “a donor-advised fund for conservatives,” the Diana Davis Spencer Foundation, which supports “free enterprise” and “America’s founding values,” and the Sarah Scaife Foundation, which donates to conservative groups. It has also funded programs at other universities like the UPenn Initiative for the Study of Markets.

In a speech in 2022, Tellez notably denounced “cultural Marxism”,197 today a well-known trope of the far right; he has also referred to the foundation as “part of the front line of the cultural battle in which we must all participate.”198 He has also noted how FEHE “nurtures a broad network of friends that is dispersed through society, working diligently and quietly to bring about change.” Working within elite universities, he has said, is “the key leverage point for cultural change today.”199

While Tellez continued to spread the gospel across American campuses, in Australia, a 2023 investigation by the country’s public broadcaster ABC, called “Purity: An Education in Opus Dei”, brought to light the impact of Opus Dei on that country’s education system. The documentary revealed unethical practices at elite Opus Dei schools, including failure to follow the state curriculum, teaching misinformation around sexual health, and attempts to recruit students,200 with some classes being taught by numeraries.201 In one instance, recounted in the documentary, a student attending a homework club at an Opus Dei centre in Australia found a sheet with the name of each child; marked next to each name were their weaknesses, as well as their strengths, should they be recruited into the organization.

Following the documentary’s release, alumni noted that other victims of the school had come forward.202 Together, in an open letter, they accused the schools’ operator, the Pared Foundation,203 of refusing to take the steps necessary to address the issues highlighted by the film.204 They also accuse the schools of subjecting students to “an aggressive and manipulative recruitment strategy they are not even aware they are participating in.”

Finally, they accuse the schools of, among other things: presenting misleading or even harmful information, homophobia and transphobia, bigotry and intolerance, including towards other faiths, shaming of students, and even the “glorification of self-harm.”205 Alumni have noted that their concerns had been dismissed by the New South Wales Education Standards Authority.206 However, following the film’s release, the federal government directed the Authority to look into whether the schools were failing to implement the full curriculum.207

Gareth Gore has warned that, over the years, too many have been willing to turn a blind eye to Opus Dei’s many scandals because of the organization’s important place within the Church. Many people, he has noted, “happily send their Children to [Opus] schools, thinking ‘It’s a Catholic organization. What could go wrong?’”208 Opus Dei has a “veneer of holiness and good work,” he says, which means many people, especially Catholics, find it hard to believe what’s really going on. Criticism, they think, must surely be coming from people with an agenda against the Church.209 In response to the indictment in Argentina, the current prelate of Opus Dei, Fernando Ocáriz, has claimed he would “help bring healing” to anyone “hurt” by the organization, setting up, in response, an “office of healing and resolution.”210 A similar “healing and listening” office has been opened in Spain, also to promote “healing” for former members of the prelature.211

Until recently, it has indeed been easy for Opus Dei to wash their hands of the scandals that have followed it, casting blame, instead, on individuals. However, recent Vatican activity suggests these legal and structural changes may be imminent: the Holy See appears to be preparing to dismantle Opus Dei’s single juridical structure and reconstitute its functions across separate canonical entities: a clerical prelature composed only of its incardinated priests, a renewed Priestly Society of the Holy Cross for diocesan clergy, and a distinct public association of the faithful for lay members, effectively separating clerical and lay governance and curbing the prelature’s previous autonomy.212

Those reforms are being framed as a technical implementation of Pope Francis’s 2022 curial changes, which, among other things, tightened the Holy See’s authority over statutes and governance.213 Reports also indicate that Opus Dei drafted new Statutes and presented them to Rome in mid-2025, even as Vatican sources reportedly pressed for a clearer separation between clerical and lay structures and stronger Vatican supervisory powers — measures that would limit Opus Dei’s ability to operate across dioceses as a single, semi-autonomous corporate body. Some journalists and commentators interpret these moves as a de facto “breaking up” or severe curtailment of Opus Dei’s historic institutional reach; others argue the changes are primarily canonical reclassification rather than outright suppression, and that much depends on the final text the Holy See approves and how it is implemented in practice.214

Gore, in writing Opus, had said that he hopes his work, along with the recent indictments, may mean that, at the very least, people become aware of the organization’s real impact and influence. “[Opus Dei] can no longer say that it was an individual, a rotten apple. It’s all by design.”215