In the run-up to Bangladesh’s general election in January 2014, New Delhi took the unusual step of sending a top diplomat from its external affairs ministry to Dhaka to persuade General Hussain Muhammaed Ershad, the country’s former military ruler, to participate in the polls. Big questions had been raised over the fairness of the election. The incumbent government was led by Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League, and the leader of the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) had been placed under virtual house arrest, with police and roadblocks around her house in Dhaka. The BNP and other opposition parties were threatening to boycott the election. Ershad, the head of the Jatiya Party, was perceived as a potential kingmaker, able to bring to power whichever of Bangladesh’s two main parties he supported, but he was also threatening to withdraw from the election.

He later told reporters that the Indian diplomat’s purported reason in asking for his participation was to prevent the rise of the Jamaat-e-Islami, a hardline Islamist party and an ally of the BNP. However, India’s move was seen as trying to legitimise a one-sided election. This marked a pivotal moment in the relationship between the two countries, as the action was widely interpreted as direct Indian interference in Bangladesh’s domestic politics with the aim of bolstering a favoured strategic political ally in the Awami League. He told it years later

In that election, 154 out of the 300 parliamentary seats had a single candidate standing due to the boycott, resulting in the Awami League securing a majority even before voting commenced. With support from New Delhi, where the Indian National Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) was then in power, Hasina reneged on her promise of a subsequent new election and a political resolution to the question of the conduct of elections in Bangladesh. Earlier, the country had followed a system where a caretaker government took power at election time to ensure fair polls – but Hasina had abolished this in 2011, fuelling the opposition’s protests of foul play. The broken promise after the boycotted election triggered a prolonged period of governance without a viable opposition. And despite expectations of a shift in New Delhi’s Bangladesh policy following the transition of power in India in 2014, when the UPA gave way to the National Democratic Alliance led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), India’s support for Hasina remained steadfast. Throughout the ten years of Indian government under the BJP and Narendra Modi, this has remained unchanged.

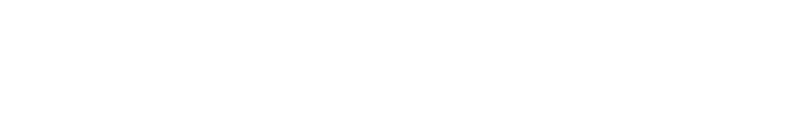

The Awami League has had more interaction with the BJP-led national government in India over the past decade than it had with Congress-led governments in the past. This is despite historical ties between the Awami League and the Congress, closer ideological alignment between them particularly on secularism, and strong bonds between the Mujib and Gandhi dynasties that, respectively, head these parties. Modi and Hasina have touted their relationship as being unparalleled in its depth and cooperation, and held it up as a model for others to emulate. Since 2014, bilateral relations between Modi’s India and Hasina’s Bangladesh have not only deepened but also expanded, transcending ideological barriers between the BJP, which is rooted in Hindutva principles, and the ostensibly secular Awami League.

But some critics have long decried a lack of mutual respect in the India-Bangladesh relationship. They have pointed out that Hasina has risked alienating conservative Muslims in her own country with gestures like inviting Modi to be a special guest at Bangladesh’s celebration of the golden jubilee of its independence.Anti-India sentiment has spread and intensified in Bangladesh especially after Hasina’s contentious re-election earlier this year. Once again, the election was highly controversial, with a crackdown on the opposition and widespread accusations of official favouritism. New Delhi had lobbied before the election for the continuity of Hasina’s government, and endorsed her contested mandate after the vote. This ignited a spontaneous backlash against India, and re-opened old wounds in Bangladesh over killings by Indian forces along the countries’ mutual border, the unequal sharing of water between them and India’s strongarm trade tactics.

Dissatisfaction with Hasina’s government has by now gone beyond just sentiments of anti-incumbency. The anger against India, meanwhile, has built up into an “India Out” campaign, so far mostly involving online influencers advocating for the boycott of Indian products. The backlash against Hasina, and consequently India, has grown significantly over the five months since the election.

The relationship between India and Bangladesh holds a profound significance, rooted as it is in India’s pivotal role in the emergence of Bangladesh as an independent nation as well as centuries of shared history and culture. Despite these strong bonds, geopolitical dynamics and economic interests have occasionally introduced friction. Notably, China’s expanding influence in the Southasia region and beyond has made Bangladesh an unexpected arena of geopolitical rivalry, involving not only the traditional Asian adversaries of India and China but also the United States.

Anti-India sentiment

Hasina’s 2024 victory was marred by controversy to such an extent that The Economist labelled it a “farce” and numerous Western governments, including the United States, deemed it neither free nor fair. The opposition largely boycotted the election after the government cracked down on its main rival, the BNP. Its leader, the former prime minister Khaleda Zia, has been under house arrest since 2017 on dubious charges. The Awami League government detained thousands of opposition activists and leaders, and the lack of genuine electoral choice resulted in significantly diminished voter turnout, estimated by at least one independent observer to be as low as ten percent. This contrasts with the official figure of approximately 41 percent, which itself is less than half the turnout seen in Bangladesh’s last genuinely competitive election back in 2008. The 2024 election was the third consecutive one in Bangladesh plagued by boycotts and widespread irregularities.

China and Russia vied with India to extend support to Hasina’s government in the 2024 election. In fact, Bangladesh managed to stave off international isolation in response to its unfair polls largely due to India’s diplomatic support, with subsequent backing from China and Russia. This echoed India’s endorsement of Hasina’s previous two election victories, in 2018 and 2013, which were also highly controversial.

Strong anti-India sentiment has festered for decades in Bangladesh due to numerous grievances. Among the most prominent of these stem from the relentless border killings of civilians by India’s Border Security Force (BSF). The BSF says that the deaths are due to its actions against cross-border smuggling, particularly of cows and drugs. However, many of the victims are ordinary people who stray into no-man’s land in the border areas or are caught ostensibly violating the unnatural border that often runs right through their homesteads and farmlands. In 2009, the United Kingdom’s Channel 4 labelled the India-Bangladesh border “the world’s deadliest border”. More recent data from the human-rights organisation Ain o Salish Kendra indicates that at least 31 Bangladeshis lost their lives at the border in 2023 alone, and that 28 of them were shot dead. Despite Indian efforts to better secure the border, such as by erecting wire fencing along most of the 4096-kilometre frontier, these killings persist.

In 2015, the BJP-led government in New Delhi claimed a notable achievement in the India-Bangladesh relationship, in the form of parliamentary approval for a Land Boundary Agreement. As part of this, India agreed to exchange contested border enclaves with Bangladesh, an effort that promised to de-escalate border tensions. In all, 111 enclaves were transferred to Bangladesh and 51 to India, with people living in these enclaves allowed to choose residence and citizenship of either country. Bangladesh had already ratified this agreement in 1974, and had been waiting more than four decades for India to sign on. India had been dragging its heels, worrying about a backlash in the state of West Bengal over the higher number of areas being transferred to Bangladesh. But today, despite the deal finally being signed, border tensions endure.

Another longstanding dispute is over the sharing of waters from over 50 rivers that flow through both India and Bangladesh – with the issue of the Teesta River especially continuing to fester. The Ganges Water Sharing Treaty of 1996, though celebrated, has left Bangladesh dissatisfied, particularly as India fails to release promised shares of the river’s waters during dry seasons, leading to significant adversity for downstream communities. Much of the problem arises from inaccurate data on downstream waterflow in the Ganga.

A third sticking point is migration. India has raised concerns about alleged large-scale economic migration from Bangladesh into its Northeast and into West Bengal, both of which border Bangladesh. This narrative is primarily driven by the BJP and its Hindu nationalist allies, which espouse anti-Muslim sentiment. Hundreds of thousands of Bangla-speaking Indian Muslims in Assam and West Bengal face threats of forced deportation after being deemed “Bangladeshi”, and no less a figure than Amit Shah, a senior BJP leader and India’s current home minister, have labelled them “termites”. Another factor exacerbating tensions is India’s Citizenship Amendment Act, under which the BJP government has established a policy of granting citizenship and resettlement packages to Hindus purportedly fleeing persecution in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The law is widely understood to be anti-Muslim since it pointedly denies the same rights to Muslim individuals.

There are occasional reports of forced migration from Bangladesh into India, but the BJP’s widespread fearmongering over Bangladeshi migration is disproportionate to the facts and is widely viewed as an attempt to stoke anti-Muslim sentiment in the region. In contrast, there has been little issue over the new and more prominent phenomenon of workers from India migrating to Bangladesh due to shortages of skilled labour as the latter’s economy has grown. A 2015 study by the Centre for Policy Dialogue, a Dhaka-based think tank, found that about 500,000 Indian nationals work in Bangladesh and that their annual remittance hovers between USD four billion and USD five billion. These figures are likely much higher today.

Security concerns have also plagued the bilateral relationship, particularly when it comes to New Delhi’s apprehensions about separatist rebel groups from India finding refuge in Bangladesh. Such tensions were rife during Hasina’s first term as prime minister between 1996 and 2001. In 2004, arms allegedly intended for separatist groups in India were recovered at Chittagong Port. Some of the tensions around this issue eased after Hasina returned to power in 2009 and took a strong stand against separatist groups fighting against India, including the United Liberation Front of Asom. Alleged state patronage of separatist rebels, however, has not been a one-sided affair. In the past, India supported with money and arms the tribal insurgents known as the Shanti Bahini, from Bangladesh’s Chittagong Hill Tracts. This enabled the group to wage a bloody war against the Bangladesh government for nearly two decades. The insurgency ended in 1997, when Hasina formulated a political settlement with the rebels and signed a peace deal. Although insurgencies in both countries have waned, political stability in India’s Northeast, which has long been a hotbed of militancy, remains fragile – as exemplified by the ongoing violence in Manipur.

Many Bangladeshis oppose aligning with an increasingly autocratic regime in New Delhi that interferes in its neighbour’s domestic affairs under the guise of pursuing regional stability and security. Concerns also linger about India’s future trajectory and the possible consequences for Bangladesh, particularly given the BJP’s emphasis on Hindu nationalism and aspirations to assert itself even more as a regional superpower.

Tricks of trade

Over the past 15 years, economic ties between India and Bangladesh have witnessed remarkable growth, resulting in a roughly four-fold increase in official trade. Informal trade, which was already taking place at high levels because of numerous border haats – temporary markets that operate year-round – may have grown to account for as much as three-quarters of recorded trade, according to some estimates. As far back as in 2007, the economist Jayshree Sengupta estimated that this informal trade itself was worth about a billion dollars.

Bangladesh has also emerged as a significant consumer of Indian services, particularly in tourism and medical care. A study by the Indian Institute of Tourism and Travel Management in 2016 revealed that Bangladesh is a substantial tourist market for India, with arrivals growing to 1.38 million that year from less than 200,000 in 1981. Notably, 77 percent of these visitors were on tourist visas, 7.3 percent on medical visas and 5.9 percent on business visas, with per-capita spending averaging INR 52,022 – making for a total spend of over a billion dollars in 2016. After disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, tourist flows have rebounded, facilitated by new transportation links that include expanded bus and train routes between the two countries.

India’s internal trade has benefited significantly from the expansion of transit facilities and Bangladesh’s granting of access to both of its maritime ports, at Chittagong and Mongla. This access allows Indian businesses in the Northeast and elsewhere to slash transportation costs by more than half in many cases.

Yet within the quadrupling of bilateral trade over the last 15 years there is also a lopsided scenario of Indian exports to Bangladesh soaring to USD 16 billion while Indian imports from the country lag at a meagre USD 2 billion. Official statistics reveal Bangladesh to be India’s fourth-largest export destination globally since 2016, following the United States, the United Arab Emirates and China. Moreover, India has emerged as a key energy supplier for the country, with exports of power, liquified natural gas and oil. In 2017, the Adani Group, a consortium close to the Modi regime, signed an agreement to supply power to Bangladesh from a coal-based power plant in the state of Jharkhand. Several experts have called out Hasina’s government for favouring Adani with terms that put Bangladesh at a disadvantage.

Perhaps the Modi government’s attitude towards Bangladesh can best be gleaned from Why Bharat Matters , a recent book authored by India’s foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar. He writes, “Economic priorities at home will always be a powerful driver of policies abroad.” Expounding on the idea of an Indian civilisational resurgence – an “India that is more Bharat” – Jaishankar asserts the emergence of “a New India” that is capable of defining its own interests, articulating its own positions, devising new solutions and advancing its own unique model. This discourse extends to India’s policies concerning neighbouring nations, where, Jaishankar says, “The mandala of its diplomacy has taken a clear form,” as evident in the Modi government’s Neighbourhood First policy and the expansion of Indian influence.

However, economic diplomacy is a labyrinth of complexities and contentions. While bilateral relations are generally all transactional, some relationships are marred by one-sidedness, inequality and exploitation. In the era of free trade, competitiveness might explain the accumulation of a substantial trade imbalance. The widely held perception of Indo-Bangla trade is that Dhaka has consistently been pressured into unfavourable arrangements, as with the Adani deal. Numerous trade associations in Bangladesh have alleged the imposition by New Delhi of non-tariff barriers on items where Bangladesh holds a competitive advantage. Moreover, it has become a common trend that whenever Bangladesh faces shortages of essential food items such as rice, onions and sugar, India imposes export bans on them. Bangladesh now relies heavily on India for essential commodities instead of importing them as it earlier did from countries such as Egypt, Turkey and Brazil, which only exacerbates its vulnerability.

Another startling decision by the Modi government was the suspension of the supply of AstraZeneca vaccines to Bangladesh during the Covid pandemic, despite Bangladesh having made advance payments to the Serum Institute of India for millions of doses even before production of the vaccines commenced. These doses were crucial for protecting frontline workers, And this action deviated from India’s purported “Neighborhood First” policy. At this critical juncture, China stepped in to help Bangladesh with its Sinopharm vaccine.

After a decade of Modi’s reign in India, people in Bangladesh are angry at their government cosying up to a Hindutva regime in New Delhi and tired of India’s influence in their domestic matters

India also continues to fall short in assisting Bangladesh’s development endeavours. In financing projects for infrastructure development, India’s interests and commitments are seen to be largely focused on regional connectivity. meant to facilitate transshipment and transit links. However, reciprocity, particularly in the form of providing transshipment facilities for Bangladeshi exports and services for Nepal and Bhutan, remains elusive. Additionally, New Delhi’s promised credit facilities and fund disbursements are disappointingly slow. According to a report by Business Standard in August last year, during a review meeting of projects under India’s Line of Credit – a USD 7.2 billion programme under which India extends loans to other countries for development work – it emerged that India had disbursed only 20 percent of funds announced in the previous 13 years.

India’s political intervention in Bangladesh in favour of a particular party that has marginalised its opposition and imposed de facto one-party rule raises questions about New Delhi’s disregard for the sovereignty of neighbouring countries. Bangladesh anticipates little difference in India’s attitude towards Bangladesh after the current Indian election, no matter whether Modi’s BJP returns to power or Rahul Gandhi’s Congress-led INDIA coalition cobbles together enough seats to form a government. An undercurrent of popular mistrust and disenchantment now runs through Bangladesh regarding the Indian leadership’s professed friendship to the country. Should the BJP secure an overwhelming majority, and from there potentially alter India’s secular constitution and strive to revive “Hindu civilisation” as advocated by its extreme right-wing base, the dynamic could shift dramatically.