On 10 December 1962, as London emerged from a thick smog, Duncan Sandys – MP for Streatham, Churchill’s son-in-law, and secretary of state for the colonies – stood up in the Commons and made a statement.

“Early on Saturday morning an attempt was made to overthrow the Government of the autonomous State of Brunei. This was organised by an underground body which calls itself the North Kalimantan National Army… Attacks were made on the police station in Brunei town and on various Government buildings, and the rebels seized control of the oilfield at Seria.

“The Sultan of Brunei asked us for urgent assistance in restoring law and order, which he was entitled to do under his Treaty with Britain. On receipt of this request, troops were despatched immediately by air and sea from Singapore,” he said, listing which units were involved.

He didn’t mention that the North Kalimantan Army was closely connected to the Brunei People’s Party, which had won all but one of the seats in the country’s election earlier that year – its first, and, to date, last, vote.

The party was opposed to Britain’s colonial oversight, broadly opposed to the Sultan, and opposed plans for Brunei and its neighbouring territories on the still-British controlled north coast of Borneo to join the newly assembling Malaysia – instead wanting a united, independent North Borneo.

Who rules Brunei?

The uprising was triggered by the Sultan’s refusal to compromise with these elected leaders. There was some resistance to the idea that Britain ought to police resistance to an autocrat. Responding to Sandys’ statement, the Liberal leader Jo Grimmond asked pointedly: “Are we responsible for internal order in Brunei?”

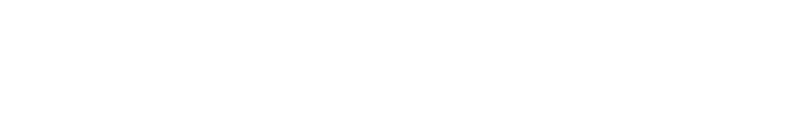

Six decades later, this question is still pertinent. The current Sultan – Hassanal Bolkiah – was personally rescued alongside his then-ruling father by British army Gurkhas during the attempted revolution. He took over in 1967, and asked the British army to stay, protecting his regime. It’s still there.

Since the country became fully independent in 1984, Bolkiah has ruled his 460,000 subjects as an absolute monarch, appointing himself prime minister, foreign minister, finance minister and defence minister.

There are no elections. There’s no free press. In 2019, he implemented a law prescribing death by stoning for adultery and gay sex in certain circumstances.

“The whole country feels like one big road, with jungle on one side, and a beach on the other,” says a contact who lived there briefly. “There’s basically one city, which has one big mosque and one big shopping mall,” which are its main social centres, says my contact.

The buildings – including the mosque and shopping mall – are “austere, characterless,” they add. In other words, it’s still an oil industry frontier town. Because Brunei has vast oil wealth, it’s not needed to deforest, meaning the rainforest is “this immaculate little, frozen-in-time bit of jungle that’s very rugged.”

Gurkha garrison

This testing landscape provides part of the excuse for the UK’s presence in Brunei, where the British army has its jungle warfare training school.

“The garrison is really bizarre. You’ve got a manicured lawn in a tropical country, next to a huge beach,” they continued. “There’s jungle behind you, and Gurkhas playing bagpipes.”

The roughly 2,000 British soldiers there include one of two battalions of the Royal Gurkha Rifles – with the other being based in Kent. They are mostly Nepali citizens who were recruited into the British Army under a colonial arrangement that began in 1815 and was modified in 1947 after Indian independence.

And they are, essentially, mercenaries. The Sultan pays for their presence, and then borrows personal guards from among them. As well as providing security for the Sultan, these Gurkhas host rolling visitors from across the British military at their jungle training camp.

But the relationship is much more than transactional. The Sultan, who studied at Britain’s military college, Sandhurst, is also an honorary admiral of the British Navy, and honorary air chief marshal of Britain’s air force.

The highest court of appeal in the country is still the Judicial Committee of Britain’s privy council – though, unlike any of the other former colonies over which British judges retain jurisdiction, they are officially representing neither the British monarch nor themselves. They act on behalf of the Sultan.

All this is not enough for the Tony Blair Institute, who warned in a recent report that “the UK’s position in Brunei seems vulnerable” to being surpassed by Chinese influence, with a “substantial risk that the UK’s standing in Brunei is compromised”.

Shell’s Sultan

This British presence has long been questioned. In 1966, Labour prime minister, Harold Wilson told the Commons that “the question of a permanent and unending commitment” in Brunei, “with a Government who have not been noted for democratic advance of the area, raises very great difficulties for us”.

He decided to remove British troops. Despite the young Sultan making multiple trips to London to beg them to remain, Labour was resolute, and had a date for departure set in November 1970. But the Tories won a surprise victory in the election in June that year, and reversed the policy. And that’s how it remains.

To understand what’s really going on, it’s worth considering that the British base in Brunei isn’t in its capital – Bandar Seri Begawan – but in a small town to the West, called Seria – the oil capital. Indeed, in Sandys’ initial statement to the Commons, he and MPs responding seem particularly concerned about the fossil fuels.

And, since 1929, Shell has played a major role extracting Brunei’s plentiful hydrocarbons. Brunei Shell Petroleum, which extracts the vast majority of the oil, is half owned by the state, half by Shell.

Of 222,000 people in employment in Brunei, around 24,000 are employees of or contractors for this offshoot of Britain’s biggest company. Around one in every 200 people in Brunei is a British soldier. These numbers are not coincidental.

75% of Brunei’s government revenue comes from the oil and gas sector i.e. from Brunei Shell Petroleum. In other words, while the Brunei government pays for the British soldiers propping up the regime, Brunei Shell Petroleum is paying the Brunei government.

The Sultan is, in a sense, an extremely wealthy middle man, providing dynastic legitimacy for British troops to secure a small corner of north Borneo for a British oil company.

Super-rich

This role allowed the Sultan to become – in the 1990s – the richest man in the world. While his wealth – around £30bn – pales in comparison to the new billionaires like Elon Musk, he is still extremely wealthy.

And much of that money is spent in the UK: he and his family are believed to have bought roughly half of all the Rolls Royce’s produced in the 1990s – a vast subsidy to the British company.

He has billions of pounds of property in the UK – both investments, and private homes in which it’s believed he spends a significant portion of his time.

Brunei is a tiny dictatorship on the other side of the world, slightly smaller than Devon. But, at any one time, around one in forty British soldiers is based there, propping up a despotic ruler so that Shell can keep pumping oil and gas out of its rocks, to be burned, and, in turn, help burn the planet.

Britain provides this service to the oil giant despite the fact that, for the five years to 2023, Shell paid no tax in the UK.

Debating Brunei in parliament in 1970, the Left wing MP Stan Orne described the Gurkhas’ presence there as “an anachronism”. Fifty five years later, it’s a feature of the modern world.