After they were captured by ICE, after they were booked for deportation proceedings from the US, and after they were put on a plane bound for the Ghanaian capital of Accra, the deportees arrived at what would be their temporary ‘home’ in Ghana: the Bundase Military Camp.

At the camp, an active military training base just outside Accra, none of the deportees had access to running water or bedding, women were denied sanitary products, and those who were sick were denied healthcare, according to Oliver Barker-Vormawor, a lawyer and the convener of Democracy Hub, a Ghanaian civil society organisation, who is representing 11 of the deportees in court. “The place was not designed to keep humans,” said Barker-Vormawor of the conditions the deportees told him they were held in.

Barker-Vormawore believes 42 deportees have arrived in Accra from the US in groups of around 10 to 15 over the past few weeks, after Ghana joined a growing list of African countries, including Eswatini, Rwanda and Uganda, to controversially agree to take in people deported by the US’s increasingly far-right-leaning government. The lawyer said the Ghanaian government’s secrecy makes it difficult to establish the exact number of arrivals.

President Donald Trump’s controversial decision to detain, imprison and deport individuals in the United States to third countries without due process has grabbed headlines around the world. Less visible is how his administration is using the lives and liberty of vulnerable people as bargaining chips to extract concessions from nations like Ghana, where the national government stands accused of undermining national sovereignty and flouting international protocols and law in a bid to curry favour with the US.

After they were captured by ICE, after they were booked for deportation proceedings from the US, and after they were put on a plane bound for the Ghanaian capital of Accra, the deportees arrived at what would be their temporary ‘home’ in Ghana: the Bundase Military Camp.

At the camp, an active military training base just outside Accra, none of the deportees had access to running water or bedding, women were denied sanitary products, and those who were sick were denied healthcare, according to Oliver Barker-Vormawor, a lawyer and the convener of Democracy Hub, a Ghanaian civil society organisation, who is representing 11 of the deportees in court. “The place was not designed to keep humans,” said Barker-Vormawor of the conditions the deportees told him they were held in.

Barker-Vormawore believes 42 deportees have arrived in Accra from the US in groups of around 10 to 15 over the past few weeks, after Ghana joined a growing list of African countries, including Eswatini, Rwanda and Uganda, to controversially agree to take in people deported by the US’s increasingly far-right-leaning government. The lawyer said the Ghanaian government’s secrecy makes it difficult to establish the exact number of arrivals.

President Donald Trump’s controversial decision to detain, imprison and deport individuals in the United States to third countries without due process has grabbed headlines around the world. Less visible is how his administration is using the lives and liberty of vulnerable people as bargaining chips to extract concessions from nations like Ghana, where the national government stands accused of undermining national sovereignty and flouting international protocols and law in a bid to curry favour with the US.

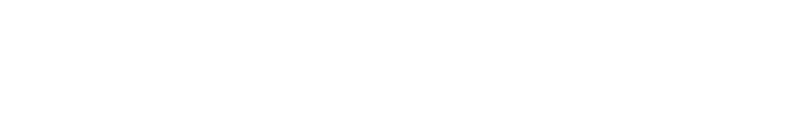

Announcing the plans in September, President John Dramani Mahama said Ghana would only take in people of West African origin, and that they would be repatriated back to their home countries through the free movement permitted to members of the Economic Community of West African States. openDemocracy has reviewed court documents concerning the 11 deportees Barker-Vormawor is representing, which confirm that all are West African and none are Ghanaian.

While the deportees were at the military base, they were denied external contact with friends, family and lawyers, according to Barker-Vormawor, who was able to get in touch with them after they were released and transferred out of Ghana. Disturbed by the conditions in which they said they had been held, his organisation, Democracy Hub, filed two lawsuits against the Ghanaian government in an effort to set a legal precedent to prevent similar arrangements in the future.

The first lawsuit, at the Human Rights Court in Ghana, argued that the detainment of the 11 deportees breached Ghana’s constitution and the country’s international obligations under the 1951 Refugee Convention, the Organisation of African Unity’s Refugee Convention, and the UN Convention Against Torture, which forbid returning people to home countries where they could face persecution or torture.

The second lawsuit, filed at Ghana’s Supreme Court, challenged the government’s initial decision to receive any US deportees on the grounds that Ghana’s constitution restrains the president from signing such agreements without Parliament’s assent and ratification.

This has been dismissed by President Mahama’s supporters, who insist he did not need parliamentary approval to sign the deal. Mahama Ayariga, Parliament’s Majority Leader and a member of Mahama’s party, has said that the government acted in the broader national interest.

On 28 October 2025, the Supreme Court gave the Attorney-General’s Department two weeks to respond to these applications, describing the matter as one of significant public interest. The court noted the attorney-general’s absence in court and previous failure to respond to the group’s requests for discoveries and an interlocutory injunction, which would have temporarily suspended the US-Ghanaian deportation agreement during the court process. The attorney-general has previously repeatedly failed to turn up to court in high-profile cases, which critics say is a tactic designed to frustrate the process.

It is not the first time Ghana has taken in deportees from another country.

In January 2016, two Yemeni nationals who had been held by the US at Guantanamo Bay were deported to Ghana as part of an agreement between the Ghanaian government and Barack Obama’s administration in the US. At the time, Ghana said it had agreed to the deal, which saw the US give Ghana $300,000 to house the two men for two years, on “humanitarian grounds”.

But the following year, the Supreme Court of Ghana ruled that the country’s government had acted unconstitutionally by agreeing to take in the two men, and Parliament later ruled the detainees could apply for refugee status that would allow them to stay in Ghana indefinitely.

At the time, the then head of the Ghanaian government was in his first term. Now, nine years later, President Mahama is back in power and repeating his own history.

The Togo question

This time, though, Mahama’s government has gone a step further. Days after they arrived at the military facility, Barker-Vormawor said at least six deportees were secretly transferred to neighbouring Togo, three hours from Accra.

Under its arrangement with the US, Ghana was supposed to be responsible for the ‘transfer’ of the West African deportees, handing them over to their own respective governments through an official process. But Barker-Vormawor says Ghana’s government took the deportees – only three of whom are said to be Togolese – into Togo without passing the border checkpoints or obtaining consent from the Togolese government.

One of the six, a Nigerian man, spoke to the BBC about being “dumped” in Togo.

He said: “They did not take us through the main border; they took us through the back door. They paid the police there and dropped us in Togo.”

“We’re struggling to survive in Togo without any documentation,” the man added. “None of us has family in Togo. We're just stuck in a hotel. Right now, we're just trying to survive until our lawyers can help us with this situation.”

“The fact that Ghana sent some of these detainees to Togo without going through official borders, sneaking them in and dumping them there is alarming,” said Barker-Vormawor, who is representing the six people affected. “There should be a humane way of sending deportees back to their home countries. You cannot send people back to a hostile environment they were fleeing from.”

So far, neither the Togolese Ministry of Foreign Affairs nor the Togolese Embassy in Accra has issued a public statement confirming prior knowledge or consent to Ghana’s actions. openDemocracy has written to the Togolese ambassador to Ghana, having been directed to do so by the embassy, to ask about Togo’s position on Ghana’s alleged moving of the West African deportees to Togo, but has yet to hear back.

Daniel Dramani Kipo-Sunyehzi, an associate professor at the Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy, University of Ghana, has warned that the Togolese government is likely to respond negatively if the allegations prove to be true.

“If these reports are confirmed, it would mean the government of Ghana acted in bad faith,” Kipo-Sunyehzi said. “Togo will not take kindly to such an action, especially if it involves nationals of other West African countries being left at its doorstep without due process.”

The government’s mixed messaging

The government’s messaging around the deportation deal has been far from consistent.

“Our decision is grounded purely on humanitarian principles and Pan-African solidarity to offer temporary refuge where needed, to prevent further human suffering, and to maintain our credibility as a responsible regional actor,” Ghana’s minister for foreign affairs, Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa, told journalists at a press briefing on 15 September.

“Ghana’s decision must be understood as an act of Pan-African empathy. It is not transactional,” he continued, saying that Ghana had legal cover to take in the deportees because they are from members of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Citizens of ECOWAS member states can stay in other West African countries for up to 90 days without a visa.

Ablakwa insisted Ghana received “no financial or material benefits” for accepting the deportees.

Almost three weeks later, he gave a local TV interview that appeared to tell a very different story.

Ablakwa revealed that it was Ghana that “initiated talks with the US” over its own demands, including a reversal of the visa restrictions the Trump administration imposed on Ghana (along with three other African countries) in July. He said Ghanaian students seeking to study in the US had been severely affected by these restrictions, which limited the conditions under which people could enter the US and how long they could stay.

The foreign affairs minister said Ghana also wanted the US to extend its participation in the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a trade agreement that lapsed last month, which gave some goods from 32 African states duty-free access to the US market over the past 25 years.

The lapse of AGOA, combined with Donald Trump’s tariff war, means Ghanaian traders now face 15% tariffs on goods that once entered the US market duty-free. Samson Asaki Awingobit, executive secretary of the Importers and Exporters Association of Ghana, told openDemocracy that the additional costs have eroded profit margins and weakened the competitiveness of Ghanaian exports.

“The impact is severe and a major cost to businesses. We were hoping the government would ask for a two or three-month moratorium, but that didn’t happen.”

Awingobit believes continued delays in renewing AGOA could worsen Ghana’s trade deficit and reduce critical dollar inflows needed to stabilise the economy. He also criticised Ghana’s lack of transparency surrounding negotiations, saying: “The government should have negotiated through the African Union instead of negotiating as a single country.”

The foreign minister has denied that Ghana’s decision to take in the deportees was a concession to secure its demands, but it is worth noting that the US reversed visa restrictions on Ghanaians less than three weeks after President Mahama announced Ghana would accept West African deportees from the US.

The US is yet to act on Ghana’s other demands; Ghanaian exports to the US still face 15% tariffs, and the perks offered to Ghana under AGOA have not been extended.

Ghanaian government critics say Ablakwa’s TV interview confirms that Ghana used the deportees as a bargaining chip in its talks with the US.

International Relations Scholar at the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration, Professor Mawuko-Yevugah, told openDemocracy that since the deportees were brought into Ghana largely against their will, the ECOWAS provisions cannot be a basis for the agreement.

Democracy Hub’s suit against the government also disputes the government’s use of the ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol to justify the transfers, arguing that the protocol covers voluntary travel, not deportations from member countries.

“We cannot fight America’s battle for them. This agreement risks hurting Ghana’s reputation if it appears that we are complicit in flouting international protocols,”. Mawuko-Yevugah said.

“The minister from day one has not been truthful, open, or straightforward with the whole agreement and that is undiplomatic for a foreign minister,” said Nana Asafo-Adjei Ayeh, deputy ranking member on Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee, and a member of the opposition New Patriotic Party.

Ayeh said that the government’s decision to accept the deportees without full disclosure to Parliament undermines Ghana’s sovereignty and sets a dangerous precedent for future bilateral engagements. He said that the opposition will continue to demand accountability and intends to compel the foreign affairs minister to disclose the terms and implications of this to Parliament.

The diaspora weighs in

For many Ghanaians living abroad, the US-Ghana deportation deal has been a source of embarrassment, deep fear and disappointment – and a stain on Ghana’s long-standing reputation as a champion of Pan-Africanism.

In the Bronx, New York, where there is a large Ghanaian migrant community, the anxiety is palpable, according to Abena Aniwaa, 30-year-old Ghanaian-American who has lived in the US for more than two decades.

Aniwaa has felt the wave of deportations close to home. Her aunt’s partner was an undocumented migrant in the US, who had a work authorisation permit. But earlier this year, when he went to renew it, officers from the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) unit detained him. Soon after, he was deported to Ghana.

He had not been back to his home country in 20 years.

Amid the fear, Aniwaa’s Ghanaian church community in New Jersey has become a refuge. The church organises a support system for immigrants, helping them understand their rights and connect with lawyers who can fight deportation orders.

“It’s the only place where people still feel a bit of hope,” she said

But for Aniwaa, the pain from Ghana’s role in accepting deportees lingers. She asked: “Why are we doing this? Why are we betraying our fellow Africans?

Emmanuel Ameyaw was the lead reporter on this piece. Ayodeji Rotinwa and Indra Warnes contributed significant, additional reporting and writing.