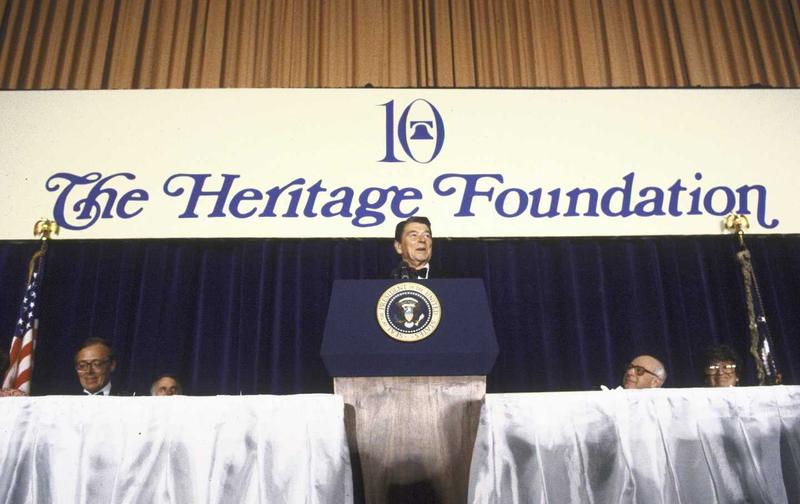

After Ronald Reagan was elected president in November 1980, the Heritage Foundation—then an upstart think tank—released a pre-publication draft manuscript of Mandate for Leadership: Policy Management in a Conservative Administration to the presidential transition team and to the press. Written over the course of 1980, the 3,000-page manuscript (1,093 pages when published as a book) reflected the aspirations of a surging political movement about to take power. When Richard Nixon was elected in 1968, let alone when Barry Goldwater ran for the presidency in 1964, there had been no comparable intellectual infrastructure that could have produced anything like Mandate. There were a handful of free-market intellectual societies and anti-communist propaganda outfits, but most were broadly ideological, offering sweeping political and economic visions rather than a detailed policy program.

By 1980, though, conservatism had come to Washington, and the entire organizational landscape had changed. Not only was there Heritage, founded in 1973 with the support of beer magnate Joseph Coors, but also the American Enterprise Institute, the Cato Institute, the American Conservative Union, and more. Edwin Feulner, then the president of Heritage, recalls that the inspiration for Mandate was a meeting at which former treasury secretary William Simon complained that when he got to Washington to serve under Nixon, he had no guidance on any “practical plans” for enacting a conservative agenda. The Heritage Foundation set to work to make sure this wouldn’t happen again under Reagan in 1981.

The idea was to offer the new administration a manual on how to restrain the federal government, in the belief that doing so would lead to an explosion of entrepreneurial activity that would power the United States back to dominance in global affairs. Reagan passed out copies of Mandate at his first cabinet meeting, and many of its contributors would win posts in his administration (most notably James Watt as secretary of the interior). The book itself became a bestseller.

This year, Heritage—through Project 2025, its umbrella coalition of conservative organizations—has released a new Mandate for Leadership, intended to guide the presidency of Donald Trump should he win the election. While Heritage does this every time a new president enters office, and twice for Republican administrations, the current Mandate—at more than 880 pages—is far more ambitious than most of the earlier versions. As in 1980, the document is supposed to indicate the “new vigor of the right,” and to this end it marshals “more than 350” conservative thinkers and “45 (and counting)” conservative organizations to provide policy advice to a new administration. Feulner himself wrote the afterword (which he retitles “the ‘Onward!’”), in which he notes that the current “economic, military, cultural, and foreign policy turmoil” echoes that of the Carter years (“actually, even worse”).

But despite the invocation of 1980, this new Mandate reflects a very different phase of American conservatism. While the right may be hoping to recapture the élan of the early Reagan administration, in tone and substance the document reveals a fractious, internally divided movement. It does so even as it suggests the real ideological transformation of the right as it has struggled to integrate Donald Trump’s electoral successes into its broader political vision.

In his foreword to the 1980 Mandate, Feulner wrote, “Political imagination and conservative philosophy are not ‘strange bedfellows,’ as some political commentators claim,” but rather “necessary and equal partners in the business of government.” Indeed, many of the authors were people with some history in Washington themselves, as congressional or cabinet staff members; out of 32, there was only one woman.

To show how conservatives would govern, the 1980 Mandate began with descriptions of the various cabinet departments and provided detailed agendas for each. The net effect was a blueprint for how American government could work if many of the executive agencies that had been created during the New Deal and the Great Society were cut back or eliminated. The Department of Education should be “completely restructured” to return decision-making to state and local levels. The entire Soviet bloc should be embargoed (“all trade with the U.S.S.R., as the major world outlaw, is immoral”). Economic regulation “threatens to destroy the private competitive free market economy it was originally designed to protect” and so should be overhauled. The section on the Department of Labor called for right-to-work bills for particular groups of employees, like students or journalists, and took an especially harsh stance toward public workers, foreshadowing Reagan’s retaliation against the air traffic controllers’ strike of 1981. Influenced by supply-side economics, the report recommended ending the capital gains tax and the corporate income tax to give people a greater incentive to “work, save, invest, and produce real output.”

Reflecting the fears of the right after the American defeat in Vietnam and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the 1980 Mandate called for a revived anti-communist campaign. The chapter on the Department of Defense warned that the US was “moving toward a state of military inferiority” vis-à-vis the USSR and that the military budget had to be drastically expanded. The section on the State Department was especially harsh toward Jimmy Carter’s Central America policies, urging the United States to “discourage the Soviets in their attempts to establish another communist country in this hemisphere.”

The 1980 Mandate’s call for a new embrace of capitalism through supply-side economics and anti-communism could tolerate some nuance. On immigration, for example, the 1980 Mandate was ecumenical, pointing out that some conservatives saw the “entrance of illegal aliens” as a good way to find people to do jobs that Americans would not do at the “market price,” while others believed that “a large unassimilable foreign culture” would create “unsustainable burdens.” Although the section on the Environmental Protection Agency described its regulations as “crippling,” it also conceded that there had been “remarkable progress” in controlling pollution. There is scant mention of abortion, family values, crime, religion, or sexuality. The agenda was sweeping, but the rhetorical tone was, for the most part, cool.

Compare all this to the Project 2025 Mandate (subtitled “The Conservative Promise,” as opposed to “Policy Management in a Conservative Administration”). Where in 1980 the focus was on the structure of the federal government and on refocusing the state on national security, the current Mandatebegins by depicting the problems facing America today: inflation “ravaging” family budgets, drug overdoses, the “toxic normalization” of transgenderism, “pornography invading” school libraries, and most of all the “Great Awokening,” which it likens to a “totalitarian cult.” Kevin Roberts, the president of Heritage, warns against “globalist elites” and the “strategic, cultural, and economic Cold War” being waged by the “totalitarian Communist dictatorship” in Beijing, with TikTok as one of its major weapons.

As in 1980, the argument is that the “modern conservative president” must “limit, control, and direct” the executive branch. This Mandate also calls for the elimination of the Department of Education and envisions a “conservative EPA,” noting the agency’s roots in the Nixon administration and suggesting that “cooperative federalism” will produce a “culture of compliance.” It proposes abolishing Head Start, alleging the program is “fraught with scandal and abuse,” and argues that the Department of Justice (including the FBI) has been captured by “an unaccountable bureaucratic managerial class and radical Left ideologues.” Tax policy must be revised to “improve incentives to work, save, and invest”—almost an exact quote from the 1980 Mandate.

But what had once been a clarion call to confidently advance a conservative project now seems shrill. The vision of reshaping the state and unleashing new energies has become an “existential need,” with a weakened president overwhelmed by a state grown out of control. One suggestion for reining in the state is cutting federal salaries and benefits, described in Mandate as adopting “market-based pay”; another is dismantling the Department of Homeland Security to create a “stand-alone” border and immigration agency with at least 100,000 employees. Mandateacknowledges the divides on the right over Ukraine and Russia, but it seeks to rally the troops around “a generational opportunity” to resolve these tensions and recognize “Communist China” as the “defining threat.” It gives up any pretense of shared values around trade policy, with one essay on “fair trade” focused on protecting US manufacturing given the “existential threat” of China, and another in defense of “free trade” that suggests rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

In place of the idea that rolling back the state and unleashing the free market will lead to a revival of national power, the new Mandate offers a vision of “restoring the family.” In a loose adaptation of Edmund Burke, it accuses the federal government of “subverting” people’s “natural loves and loyalties” with “unnatural” ones. The argument is that people exist within families and communities; unless these are protected, atomized individuals will be prostrate before the all-powerful state. Transgender politics, abortion rights, smartphones, and pornography all delink people from their “natural” loyalties, with the underlying goal, presumably, of making them vulnerable to state control. Where earlier iterations of conservatism focused on liberating the individual, the 2025 Mandate seems to see communities and families as bulwarks protecting defenseless individuals from the otherwise overweening power of the state.

Unsurprisingly, Mandate aligns itself in opposition to “corporate and political elites,” arguing that “nearly every top-tier U.S. university president or Wall Street hedge fund manager has more in common with a socialist, European head of state than with the parents at a high school football game in Waco, Texas.” But the distance from earlier versions of conservatism is nonetheless remarkable. We’re told that labor policy should be revised to focus on “the good of the family,” with on-site childcare and more paid time off. Congress is enjoined to “encourage communal rest” by amending the Fair Labor Standards Act to mandate overtime pay for people who must work on the Sabbath. Family authority is the model for the nation: “As the family necessarily puts the interests of its members first, so too the United States must put the interests of American workers first.” The document sets itself the aim of uniting the “conservative movement and the American people” in a campaign against “elite rule.”

In his foreword, Roberts is careful to position Mandate as the work of a broad movement, noting that it serves as an agenda “by and for conservatives” who want to be ready on day one to “save our country from the brink of disaster.” As part of Project 2025, Heritage has been building a database of personnel who might serve in a Trump administration—especially important because, as Mandate suggests, “political appointees who are answerable to the President” are key to carrying out its vision. But Trump’s campaign, as Sam Adler-Bell has reported, has been careful to distance itself from Project 2025’s efforts—as though they threaten to siphon political energy from the singular goal of electing Trump.

Still, even if a reelected President Trump should ignore the suggestions provided in Mandate, the document is instructive. The transformations that began in 1980 with Reagan’s election reshaped American society, just as the original group of Heritage authors suggested they would. The vision of the market and of state rollbacks that they promoted eroded living standards and wages and propelled a stunning rise in economic inequality and social hierarchy. Private economic wealth is all that has filled in the gap, and the far-right mobilization of the present—with its conspiratorial fantasies of malign takeover and internal subversion—is the legacy of the atomized, hierarchical society produced by the Reagan revolution. For all the ways that Project 2025 may fantasize about a return to 1980, we find ourselves in a very different place today. As Feulner says, “Onward!”