The Most Nefarious Coup

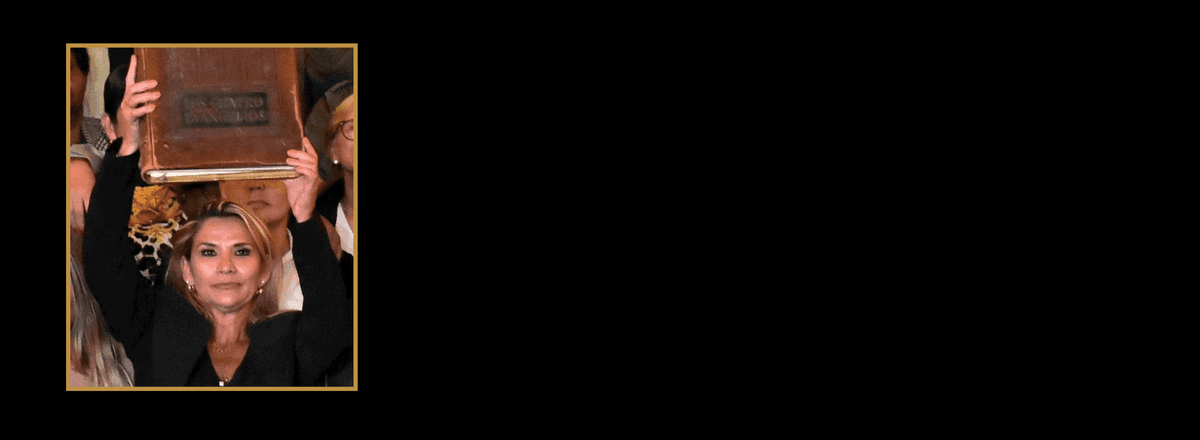

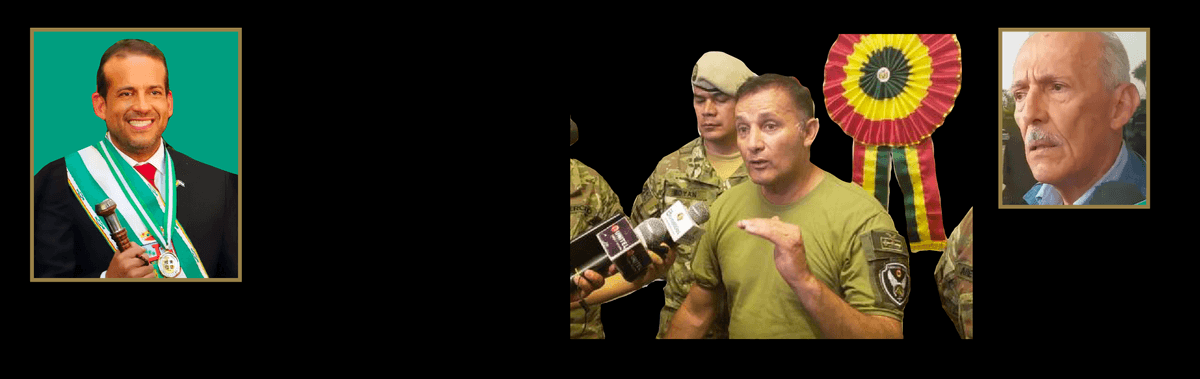

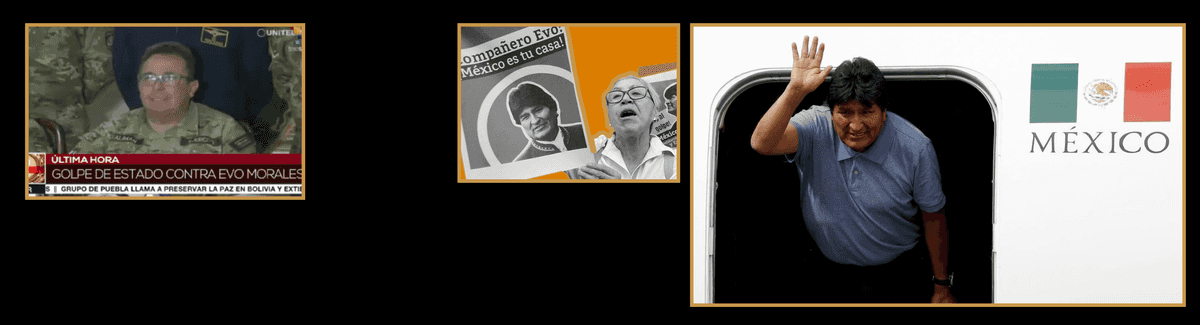

On 12 November 2019, Jeanine Añez entered the presidential palace, raised a Bible over her head and proclaimed herself the president of Bolivia. "Thanks to God who has allowed the Bible to re-enter the Palace. May He bless us and enlighten us,” she said.1 Outside, her supporters cheered as the Bolivian military bestowed on her the presidential sash. Meanwhile, armed groups terrorized supporters of ousted President Evo Morales, who landed in México that very day with the help of Andrés Manuel López Obrador. “The most treacherous and nefarious coup in history,” said Morales, “has just been consummated.”2

Bolivia in the Global Fascist Movement

But 2019 was not the first coup organized by Bolivia’s reactionary forces. Faced with an insurgent peasant movement in the 1950s, the Bolivian military orchestrated a series of interventions in the decades to come. In 1971, military official Hugo Banzer organized a military coup with the support of the Nixon administration in the United States to prevent then-President Juan José Torres from leading the country in a left-wing direction.3 Nine years later, in 1980, General Luis García Meza came to power in another violent military coup, this time with the support of famous European fascists such as Gestapo chief Klaus Barbie and Ordine Nuovo member Stefano Delle Chiaie. “It was decided to give my hand to the creation of an international revolutionary movement... Therefore, when the opportunity for a national revolution appeared in Bolivia, we were there to shoulder our comrades. We were neither repressors nor narco-terrorists, but political militants,” said Delle Chiaie in a 1997 hearing before the Italian Parliamentary Commission on Terrorism.4 The resulting Junta of Commanders of the Armed Forces became famous for its torture, disappearances, and arbitrary arrests.

The Movement Toward Socialism

In 2006, Bolivia finally broke with this history of colonial domination. Running with the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS), Indigenous leader Evo Morales rose to the presidency with a promise to improve the lives of Bolivia’s Indigenous and working majority.5 But Bolivia’s reactionary forces did not rest. In August 2008, governors from Bolivia’s eastern regions led their first coup attempt against Morales for his efforts to redistribute their gas revenues to a national pension plan.6 Protestors blew up a public gas pipeline, and clashes resulted in the deaths of 20 people in the city of Cobija — most of them humble farmers who supported the government of the MAS. The opposition, under Tuto Quiroga, blamed Morales for the violence. Many of the seeds of the 2019 coup were sown at this moment, as spaces like the Unión Juvenil Cruceñista — home to Luis Fernando Camacho — came to prominence for their violent opposition to the democratic government of the MAS. But the Morales government survived, winning consecutive elections in 2009 and 2014 before opponents of the MAS prepared to claim power by force in the elections of 2019.

Planning the ’Fraud’ of 2019

Long before Bolivians cast their votes in 2019, false claims of fraud were identified as a potential tactic to undermine the election outcome. A 2018 report by Stratfor — a consulting firm with clients such as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) — suggested that "a hotly contested election, particularly one in which accusations of electoral fraud fly, runs the risk of inflaming an already tense domestic political scene.7 Demonstrations would spread, particularly in eastern provinces such as Santa Cruz, a center of strength of the Bolivian political opposition." Months later, an anonymous source uploaded 16 audio recordings to a local blog, which detailed the steps that would lead to the coup:

- Legally annul/invalidate the elections.

- Call for a national strike on October 21.

- Generate an uprising of the citizenry.

- Get the armed forces to join the uprising.

One of the voices heard in the audios could be those of the former Minister of Government of Carlos Sánchez Berzain, Director of the Inter-American Institute for Democracy, who — following an infamous meeting of the Atlas Network with figures such as Perú’s Mario Vargas Llosa and Ecuador’s Lenin Moreno — called to nullify the vote count in order to end "dictatorship of Evo Morales."8

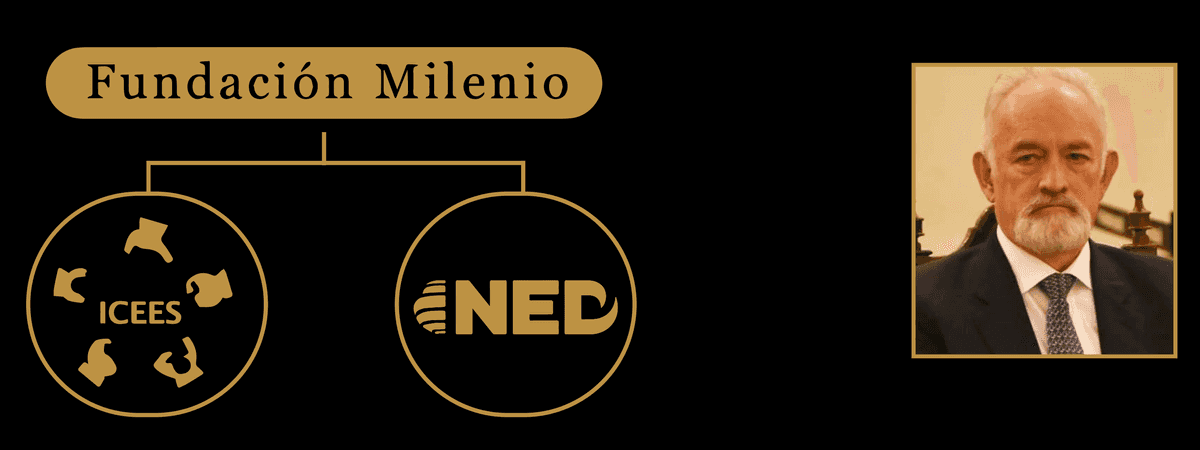

By October 2019, the forces of the Bolivian right were already proclaiming fraud. On 11 October, journalist Carlos Valverde — a US informant and member of the Instituto de Ciencia, Economía, Educación y Salud (ICEES), a member of the Atlas Network — proclaimed that a fraud was underway. On the very same day, the Frente Cívico and Luis Fernando Camacho launched the initiative Manda Tu Acta (’Send Your Ballot’), a campaign to ‘stop the steal’ of the 2019 election.9

The narrative of possible electoral fraud was then spread internationally through an article in Florida’s Nuevo Herald and disseminated by Atlas Network foundations such as the Mexican Caminos de la Libertad just weeks before the elections, claiming that Evo Morales would try to steal votes to make up for an anticipated 9-point deficit.

Lighting the Fuse

On 20 October, Bolivians went to the polls and delivered a resounding victory for Evo Morales and the MAS. The Plurinational Electoral Organ, reviewing the vote count, announced a first-round victory with more than 10 points over his opponent, Carlos Mesa. But the opposition — along with the Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), Luis Almagro — refused to accept the result.10 Without citing any evidence, Mesa accused Morales of a “shameful and crude alteration of the result of our vote.” Others — such as Carlos Mesa and Luis Fernando Camacho — joined the call to invalidate the vote, encouraging their followers to set fire to provincial electoral offices across the country.11

By Thursday of that week, both the European Union and the OAS were demanding that the Plurinational Electoral Organ retract its decision and force a new election, despite showing “no evidence – no statistics, numbers, or facts of any kind” that fraud had taken place, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington DC.12 Further research would reveal the flaws in the OAS methodology, concluding zero “statistical support for the claims of vote fraud.”

Regardless, the international press parroted these unsubstantiated claims. “Bolivia’s general elections on Oct. 20 were marred by ‘a series of malicious operations aimed at altering the will expressed at the polls,’ “ published the New York Times on 5 December.13 “Evo Morales: Overwhelming evidence of election fraud in Bolivia,” was published on BBC one day later.14

Within weeks, the false claims of fraud would harden into facts. By November, Salvador Ramero — the former Director of the USAID-funded National Democratic Institute, where he played a critical role in the prior coup in Honduras — was appointed to the Presidency of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal of Bolivia. "It is necessary to rediscover the authentic mission of the Electoral Tribunal as an institution independent of the powers and parties, guarantor of inclusive, equitable and honest processes,” Romero said at his inauguration ceremony.15

An Orchestra of Violence

With the narrative of fraud set into place, the violent plan to take power was put into action. It was a plan orchestrated in large part by the Governor of Santa Cruz, Luis Fernando Camacho, who confessed with pride his role in the plot to permit paramilitary groups to overtake the streets of Bolivia: “It was my father who negotiated with the military so they don't come out [to the streets]. It was for this reason that the person who went to speak with them and coordinate everything was [Luis] Fernando López, current Minister of Defense, and that is why he is currently Minister of Defense: to fulfill his commitments. The police in the same way, it was my father. When we were able to consolidate that both were not going out, we gave 48 hours. We gave them 48 hours because we already knew that [the protests of] Santa Cruz could move to La Paz.”16

Camacho is a key node in the network of the Reactionary International. Beyond his local leadership of the openly fascist Unión Juvenil Cruceñista, Camacho’s family owns the Grupo Empresarial Nacional Vida SA, with strong links to the evangelical movement across South America. In June 2022, Camacho and his allies in Santa Cruz signed the ‘Carta de Madrid’ in a ceremony alongside Spanish VOX Deputy Víctor González and Argentine ‘La Libertad Avanza’ Deputy Victoria Villarruel, pledging to join forces across borders to stop the “advance of communism.”17

Back in Bolivia, Camacho’s plan worked: Claims of fraud led to calls for a general strike, and the protests began to spread nationwide. Camacho found an ally in Waldo Albarracín, who gave him the University of La Paz to support the logistics and preparation of the paramilitary groups coming from Santa Cruz. By 6 November, these groups were attacking major MAS figures such as the Mayor of Vinto, Patricia Arce, and burning the houses of officials like Minister Gabriela Montaño. By 8 November, the police and military were joining in the protests, burning Wiphala flags and targeting pro-MAS activists, representatives, and family members of President Evo Morales.

Finally, on 10 November, Armed Forces commander Williams Kaliman — a graduate of the US School of the Americas military training camp in Fort Benning, Georgia — requested the resignation of President Morales. Under the barrel of the gun, Morales resigned. Within hours, Camacho stormed the presidential palace with a police escort and threw his Bible into the air. "I will make God return to the burnt Palace,” Camacho said.18

The US government joined the celebration. "After nearly 14 years and his recent attempt to overturn the Bolivian constitution and the will of the people, Morales's departure preserves democracy and paves the way for the Bolivian people to make their voices heard," President Donald Trump wrote in a White House statement.19

The New Order

With Morales out of office, the forces of the Reactionary International began the construction of a new de facto government. At the Catholic University of La Paz, a secret meeting was convened on 10 November between representatives of the Church, ambassadors from Spain, Brazil, and the European Union, and protagonists from Bolivia’s right-wing politics to select Jeanine Añez as the candidate to become the coup president.20

Less than one week later, Añez would sign an executive decree granting full impunity to Bolivia’s armed forces in return for their support for her de facto government."21 The personnel who participate in the operations to restore internal order and public stability will be exempt from criminal liability when, in compliance with their constitutional functions, they act in legitimate defence or a state of necessity.” The day after the decree, Bolivia’s military forces massacred protestors in the city of Sacaba; four days after that, they massacred another 10 in the neighborhood of Senkata.22

With Añez, a new cast of the Reactionary International would come into government. Arturo Murrillo, a businessman from Cochabamba, would be appointed as Government Minister, where he accepted a bribe of more than $600.000 from Florida company Bravo Tactical Solutions LLC in exchange for a $5.6 million contract for tear gas to be deployed against protestors in Bolivia.23

Añez, Murillo, and their allies in the coup government no longer spoke about the need to restore democracy in Bolivia; on the contrary, their demand for immediate elections was replaced by a proposal for a permanent de facto government. Instead, they spoke of a crusade against progressive forces in Bolivia and across Latin America beyond.

"We are going to hunt down [former minister] Juan Ramón Quintana, Raúl García Linera — and also people from the FARC, Cubans, Venezuelans who have been living here," Murillo said.24

Murillo later called to activate the Interpol Red Notice to demand the capture, arrest, and deportation of Evo Morales by third countries around the world.

A Coup of Global Proportions

The coup in Bolivia could not have happened without deep networks of support at the international level. That support was first evident at the release of the debunked OAS preliminary report, quickly endorsed by governments such as the United States, Colombia, Brazil and the European Union. Deputies for the Spanish far-right party VOX, Herman Terscht and Victor Gonzalez, even traveled to La Paz to deliver a government press conference alongside Arturo Murill in which they proclaimed Bolivia “the flame of freedom in Latin America.”25

Deeper interests aligned there in the form of Bolivia’s natural resources, from its fossil fuels to the world’s second-largest reserve of lithium. Back in 2018, the Atlantic Council had already warned that the MAS was putting the electric battery industry at "risk" because of Morales' "skepticism" about international investment.26 Just four months after the coup, the UK embassy organized an “international seminar” for more than 300 officials from the mining sector in partnership with the Áñez Ministry of Mining. “Due to the political changes in Bolivia, a more open environment for foreign investment is perceived and I believe that this will open new doors to companies that want to share their technology, their products and make alliances with different companies,” said UK Ambassador Jeff Glekin.27

The international press played a role as important as foreign diplomats. For years, journalists such as Carlos Valverde received funding from the US National Endowment for Democracy to attack the MAS government and the character of Evo Morales, as in the infamous “Zapata case”, when Valverde accused Morales of having fathered an illegitimate child who never existed.

In the context of the coup, these networks would be activated not only to spread the fake news of Morales’s electoral fraud but also to bolster the reputation of the Áñez government. Some of the press outlets were local, news agencies such as FIDES, directed by the Jesuit Sergio Montes, which founded Bolivia Verifica, a “fact-checking” platform partner of Facebook financed by the NED that spread fake news via the platform throughout the coup.28

Other press outlets were international. Spanish digital newspaper OkDiario, for example, dispatched its young reporter Alejandro Entrambasaguas to La Paz, where he collaborated with Arturo Murillo to spread fake news about Evo Morales and his international allies. On national television, Entrambasaguas spread the lie that Evo held a secret lover in Lorgia Fuentes, whom he granted with the Chinese company CAMC for millions of dollars. Lorgia was then arrested and tortured based on these lies.29

The members of these media networks thus had a front-row seat to the coup government. For example, Jhanisse Vaca — founder of Ríos en Pie, member of the HRF Foundation of the Atlas Network, and consultant to IDEA International — joined OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro as the final presentation of their debunked findings. And in return, they were rewarded. Fundación Milenio — another NED grantee and a publishing partner of the aforementioned ICEES — directly fed into the Áñez government through associates like Guillermo Aponte, appointed in November 2019 to the Presidency of Bolivia’s Central Bank.30

The Role of Digital Warfare

Social media platforms provided critical infrastructure for the coup in Bolivia — not in a decentralized and democratic manner, but rather in a coordinated and corporate one. Consider the company CLS Strategies, which had been contracted to conduct ‘astroturfed’ Facebook campaigns of attack against left-wing governments across the region — including by the Áñez government. Analysis conducted by Pandemia Digital and later confirmed by the IACHR showed that more than 100,000 fake accounts were created during November 2019 to support the coup in Bolivia. Among these actions was the payment of $4 million in advertising on Facebook, launching hundreds of thousands of tweets in at least 14 campaigns with the hashtags #EvoAsesino, #EvoEsFraude, and #NoHayGolpeEnBolivia. They were also used to viralize manipulated videos and photographs such as those which purported to show Evo Morales standing beside drug kingpins like Chapo Guzmán and Pablo Escobar.31

The case of CLS Strategies reveals a clear conspiracy with international dimensions.32 Following the revelations of their Facebook expenditure, CLS Strategies not only suspended the head of its Latin American practice but also deleted any evidence of its Senior Advisor Mark Feierstein (the former US Ambassador to the OAS and USAID Deputy Administrator with ties to the “Team Jorge” company of Tal Hanan) and partner Juan Cortiñas (former Director of Communications and Government Relations for the Federal Administration of Puerto Rico, from where he “led legislative strategies and communication efforts in Washington.”)

These social media tactics are built into broader networks of foundations — and government funding behind them. Feierstein, for example, boasted close personal ties to Roger Noriega, another former OAS Ambassador, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and signatory of the Carta de Madrid. Noriega today is CEO of Visión Américas, a consulting firm with headquarters in Washington, Bogotá and Madrid that once listed Team Jorge’s Tal Hannan as an associate — before the scandal broke of Hannan’s disinformation and hacking campaigns.

All in the Name of “Democracy”

If the coup government of Jeanine Áñez relied on international support, its actions provided support to the network of the Reactionary International, in turn. Within her first week of office, de facto foreign minister Karen Longaric moved to: suspend Bolivia’s participation in the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA); break diplomatic relations with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro; recognize Juan Guaidó as the legitimate president of Venezuela; expel over 700 Cuban doctors from the country; and join the new Lima Group, which united right-wing presidents from across the region of Latin America.

Áñez’s efforts to re-align Bolivia went beyond the country’s diplomatic relations and into its financial operations. During the Covid-19 pandemic, during which Bolivian death rates soared, Health Minister Marcelo Navajas was arrested for his purchase of 179 ventilators for $27,683 each from a manufacturer in Spain — costing almost $5 million US dollars — at more than double their original cost.33 The suspected corruption was funded by the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington DC. At the same time, the Áñez government applied for and received a $356.7 million loan from the International Monetary Fund, breaking with the 15-year commitment by prior MAS governments not to borrow from the Washington-based lender. The loan was later determined to have violated “the country’s sovereignty and economic interests”, and the “irregularly managed” money was sent back to the IMF.34

All of these moves were justified as the ‘restoration’ of democracy in Bolivia. But already, back in November, the New York Times — who had endorsed the OAS narrative of fraud by the Morales government — suggested that Áñez was “reaching beyond her caretaker mandate of organizing national elections by January.” In January, however, Áñez postponed the presidential elections again, buying time for her allies in government to commit crimes of corruption that led to at least 24 legal cases. In July, elections were postponed again, and the return of democracy to Bolivia appeared to drift onto the horizon.

Bolivia’s Popular Sovereignty, Restored

In response to Áñez postponing elections, Bolivia’s trade unions and social movements combined took the streets and closed the highways. Facing no shortage of reactionary repression, popular mobilization kept the flame of democracy alive — and ultimately forced the Áñez government to commit to October elections. The struggle to restore Bolivia’s democracy was also international. Responding to calls for solidarity, the Government of Mexico offered asylum to persecuted members of the MAS and their families. On his assumption of the Argentine presidency, the Government of Alberto Fernandez offered asylum, as well. And ahead of the elections, allies from across the world traveled to La Paz to participate in observer missions to defend their freedom, fairness, and transparency. “We warn the international community of the risks facing the recovery of democracy in Bolivia, for which we request your support and active observation,” said MAS candidate Luis Arce.35

The coup government also recognized that its survival depended on international support. Ahead of the 2020 election, Defense Minister Luis Fernando López “plotted to deploy hundreds of mercenaries from the United States to overturn the results,” revealed The Intercept in a series of documents and leaked audio recordings.36 “The armed forces and the people needed to ‘rise up,’” said Fernando López, “and block an Arce administration. … The next 72 hours are crucial.”

Just two weeks before the election, Arturo Murillo had traveled to the United States to meet with the US State Department and the OAS. Upon his return, Murillo admitted that he had purchased new military weapons under the banner of “defending democracy.” “The police will act, the army will act, we are not for decoration,” Murillo said. The night before the election, Murillo gathered Bolivia’s armed forces to the center of the capital city La Paz to inaugurate a plan called ‘Everyone For Bolivia’, which would deploy the military with the alleged aim of monitoring the election.37 He thanked them for “taking the dictator [Morales] out of office.”

But on election day, Bolivia rejected Murillo’s intimidation, accepted the risks of mobilization in the Covid-19 pandemic, and turned out to elect Luis Arce with a massive majority: 55% for Luis Arce to 29% for Carlos Mesa — with the contested areas of the original OAS report delivering an even larger victory for the MAS.38 Bolivia thus became the first country in history to restore its democracy within just one year of a violent coup to destroy it, providing a formula for resistance to the Reactionary International — local mobilization and global solidarity — that can teach progressive forces around the world.