On November 2nd 2023, right-wing protests erupted across Spain against the proposed amnesty pact between the governing PSOE-Sumar coalition and regional pro-independence parties over pardoning figures involved in the independence movements. Starting from the biggest square in Madrid, the demonstrations shifted outside the PSOE’s national headquarters on Ferraz Street. These demonstrations gathered support from the Spanish right, receiving the backing of the largest member of the European People's Party, the Spanish Partido Popular, the “national conservative” VOX Party, and the remnants of the “anti-nationalist” Ciudadanos Party.

Unusual for a national political dispute, these protests received international attention and were backed by the “post-fascist” Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni, ex-Fox News host Tucker Carlson, and the former leading candidate for the EU Commission Presidency, Manfred Weber. It also brought to the fore many previously marginal figures on the Spanish right such as Marina Seren, a UFO investigator who was marginalized from said community for her far-right views, and who claims to be a reincarnation of SS Leader Otto Skorzeny.

Spain, Europe’s Fascist Refuge

Spain has long held a place in the left’s imagination as the battlefield where the Axis and the Allies first clashed. During the Spanish Civil War, fascists, conservatives, and right-leaning liberals united behind General Franco in his coup against the left-leaning Republican government. With the support of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, nationalist forces were ultimately able to win the conflict, and Franco then established a dictatorship in the war’s aftermath. To prevent the fracturing of the right in the war’s aftermath, he forcibly merged the various factions of nationalist supporters into FET y de las JONS in 1937, which became the National Movement in 1943.

After the defeat of and occupation of Italy and Germany by the Allies at the beginning of the Cold War, the Western powers saw Spain as a potential bulwark against the communist threat. Consequently, in the early 1950s, the United States reversed its stance against the country’s participation in international institutions and signed a military-basing agreement in 1953.

During the Cold War, Spain played a key role in both Operation Gladio and Operation Condor, which were a series of US-backed political terrorism campaigns against the left in Western Europe and South America.

While these covert networks had to operate in secret in most countries they were active in, it has been famously stated that Operation Condor “was the state” in Spain.1 This allowed the country to serve as a place of asylum for far-right figures during the Cold War, including Otto Skorzeny, former head of the Waffen SS and the leader of the Die Spinne network which allowed German fascists to escape to South America; Stefano Delle Chiaie, a key figure in the political violence of Italy’s Years of Lead; and members of Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, which committed mass violence against the country’s Marxists, such as Rodolfo Eduardo Almirón.

The Second Franco Era

Under the Franco regime, officially, Spain remained diplomatically isolated due to the country’s continued association with fascist and neofascist figures. During this period, attempts were made to move towards liberalization when technocrats associated with the hardline Catholic institution Opus Dei were brought into the government and helped implement moves to liberalize the economy in the late 1950s. However, political liberalization efforts led by José Solís Ruiz and his protege, Manuel Fraga Iribarne, were largely unsuccessful, as this faction hoped to slowly transition Spain to democracy while institutionalizing and permanently consolidating the right-wing anti-communist character of the regime.2 Although Fraga, who served as minister of Information and Tourism from 1962 to 1969 in the Franco government, did help push through press liberalization, they eventually came into conflict with the more conservative and technocratic elements of the Franco regime, which led to the liberalizing faction being expelled from cabinet.

Fraga then founded the Gabinete de Orientación y Documentación (GODSA), a political institute that would eventually become his political party. He also accepted an ambassadorship in the United Kingdom in 1973 for two years and wanted to be free from Francoist censorship, as he sensed the end of the Franco regime. During his ambassadorship, he built relationships with the British Tories and the Labour Party right3 and seriously developed his political program, which called for a return to democracy, but where communists would remain excluded from the political system.4

This was aligned with United States policy during this period, which was skeptical of a quick democratic transition in the aftermath of the Portuguese Carnation Revolution, and one that supported the continued illegality of the Spanish Communist Party.5 Fraga returned to Spain in 1975 and was appointed interior minister by Carlos Arias Navarro, prime minister during the later years of the Francoist regime, who offered to invade Portugal to overthrow the Carnation Revolution. Fraga was aligned with this conservative policy and supported continued repressive measures that made him deeply unpopular among reformers. Nonetheless, he hoped to be known in history as the figure who led Spain back to democracy, albeit a restrictive one.6

Fraga used his international legitimacy and connections to build a “German-style” regime.7 In the 1970s, Fraga put significant effort into convincing the German Social Democratic Party and its Friedrich Ebert Foundation to back Spain’s People's Socialist Party led by Enrique Tierno Galvá rather than the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) led by Felipe Gonzalez. It was during one of these visits to Germany to meet with the SPD that the Vitoria massacre took place, killing five and wounding hundreds as part of workers’ protests.8

As the interior minister, he was seen by the Spanish population as culpable for the massacre, and with most European countries being led by social democratic leaders at the time, he had little institutional support in the international community. Consequently, he fell out of favor with King Juan Carlos I, and a little over one month after visiting the United States and pledging to create a liberal democracy,9 the King appointed Adolfo Suarez to lead the transition to democracy. Fraga's vision for a democracy, which saw the exclusion of the far left, failed to materialize, as Suarez legalized the communist party on April 9 1977.

The Transition to Democracy, Party Foundations, and the First Elections

The first democratic elections since the Franco putsch were held a little more than a year after Adolfo Suarez was appointed prime minister. But, as a country that had been under dictatorship for decades, the political parties contesting elections would rely on international actors to help run their campaigns. The German Free Democratic Party via its Friedrich Naumann Foundation backed the UCD10 (The Union of the Democratic Centre) in the 1977 election, on top of a semi-official institutional endorsement from the Carter Administration. The Socialist International and the German SPD decided to back the PSOE led by Felipe Gonzalez, while the more moderate PSP (People’s Socialist Party) lacked international backing.

The German CDU decided to back the Christian Democratic Team of the Spanish State (EDCEE), hoping to create a sympathetic sister party in Spain, although shifting to the UCD for the 1979 elections after the EDCEE failed to gain traction.11 Notably, the CDU's sister party, the Bavarian CSU, decided to back Manuel Fraga and his newly minted Popular Alliance Party12 providing nearly 3 million pesetas in funding13 and supporting the party through the Hanns Seidel Foundation. While the election focused on Spanish issues, the influence of the German party foundations on the electoral campaigns and programs of the parties was significant.

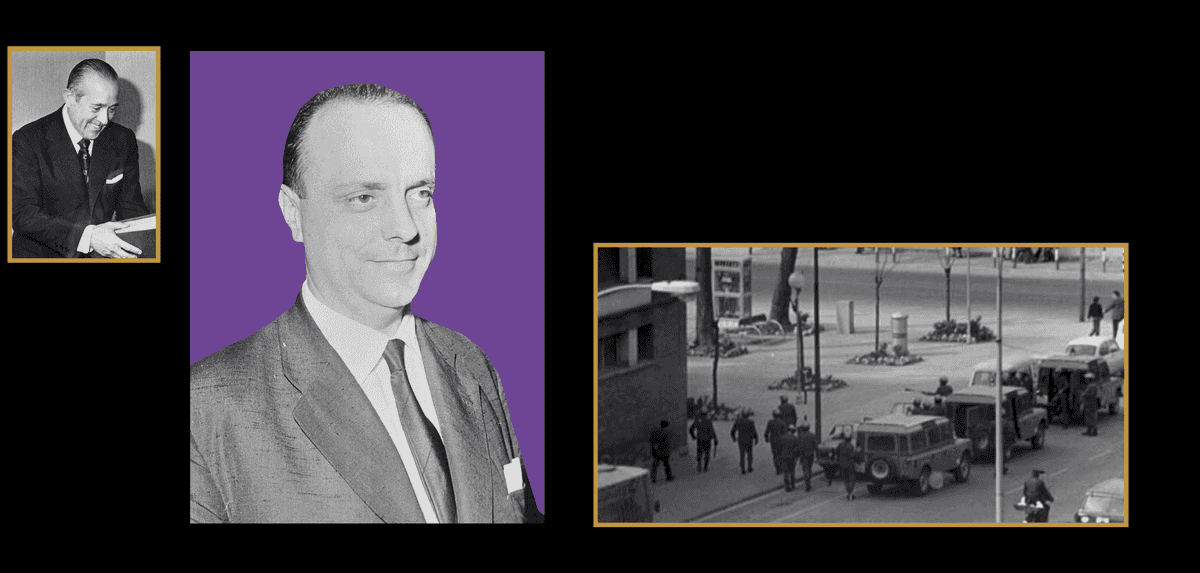

These first two elections saw the centrist UDC and the moderate left PSOE emerge as the dominant two parties. Notably, the hard Francoists got zero representation in the 1977 election and only achieved one MP in the 1979 election. Fraga’s party failed to gain more than a handful of deputies in 1977, with their position further eroding in 1979. Although it should be noted that despite seeing an overall fall in vote share, it saw an increase in the traditional conservative stronghold of Galicia, getting a similar percentage to the PSOE in the regions. However, Adolfo Suarez’s rule over Spain was unstable, and he resigned in 1981.

While parliament was voting on his replacement, neo-Francoist elements of the military attempted a coup, which further undermined the legitimacy of the UDC. Following early elections in 1982, Fraga largely succeeded in absorbing the right-leaning elements of the UDC, managing to get second place in the elections and become the leader of the opposition. Although he failed his initial goal of being the leader of the transition, he did consolidate the right.

Fraga, the IDU, and the first reactionary international

Shortly after becoming the leader of the opposition, Fraga attended the founding meeting of the IDU (International Democratic Union). Headquartered in Munich and established with the initiative of the CSU, its first meeting in London in June of 1983 brought together George W Bush Sr and Margaret Thatcher, among others. It also brought together conservative parties that were being influenced by the neoliberal shift, and Fraga hoped it would help him disassociate with the Franco regime.

However, Fraga resigned the presidency of the Alianza Popular following an internal crisis within the party14 and was replaced by Antonio Hernández Mancha, who belonged to a rival faction. Mancha was an admirer of Anglo culture and had hoped “to create a great party equivalent to the American Republican, the English Conservative, in Spain” during his leadership of the Alianza Popular.15 Domestically, he failed to make a dent against the polling lead of Felipe Gonzalez, and in an attempt to maintain control of the party, Mancha attempted to meet with Reagan in 1988.16 This was not successful in stabilizing his presidency over the Alianza Popular, although these contacts within the United States did eventually develop into a relationship with the Bush family.17

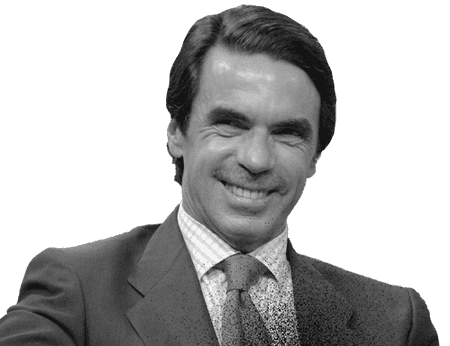

The flailing of Mancha prompted Fraga to take back control of the party’s presidency and attempt to soften its image. The Alianza Popular was refounded in 1989 and changed its name to the Partido Popular (PP). Fraga supported the candidacy of Jose Aznar to be the new president of the PP. Although the party was not victorious in the 1989 general elections, these moves succeeded in preventing a newly reemerged Adolfo Suarez from becoming the leader of the opposition.

Fraga opted against running for European Parliament once again in 1989, having become President of the Galician section in 1988 after his party had been ousted in a vote of no confidence in their traditional stronghold. He would later run for and become leader of the Xunta de Galicia in 1989. During his nearly decade and a half-rule in the region, he traveled extensively throughout Latin America, developing relationships with major figures in the region. These visits had a cynical element, as the PP has historically exerted significant influence among Spanish diaspora populations in South America. With overseas votes making up 20% of the electorate in some Galician provinces, it has been a major contributor to the party’s dominance in the region.18 But these visits also allowed for the PP to develop relationships with like-minded parties in South America, serving as the basis for later relations between the PP and the South American right.

Aznar, the EPP, and the CDI

Much of Aznar's early leadership of the PP was occupied by helping bring the party into more centrist international institutions to further improve and moderate the party’s position. The Partido Popular joined the British Tory-dominated European Democrats grouping in the 1987 European election, predecessor to the modern European Conservative and Reformist parliamentary faction in the European parliament. However, for the 1989 election, it sought to join the German and Italian Dominated European People’s Party (EPP), as well as the Christian Democrat International. However, there remained hesitation within the grouping over accepting the PP due to its association with Franco and opposition from Spanish member parties from the Basque and Catalan regions. But after significant political maneuvering, it was first admitted as a full member of the EPP in 1991, and the Christian Democrat International in 1993.19

Then during the Spanish elections of 1996, Aznar finally achieved victory, and a conservative party ruled Spain for the first time since the fall of Franco. While this gave him a great deal of prestige and the ability to develop an international network, it should be noted that in the aftermath of his victory, he became one of the only centre-right leaders in Western Europe. Bill Clinton was already in power in the United States while Tony Blair came into power in 1997. The CDU/CSU was forced out of power in 1998, Italy was ruled by the center-left Olive Tree Coalition, and while Chirac remained the president of France, the parliament was controlled by the opposition Socialist Party.

This position allowed Aznar to place Javier Rupérez as the leader of the Christian Democratic International in 1998, and make Alejandro Agag, one of his personal assistants, as general secretary of the EPP in 2000. Agag later married Jose Aznar’s daughter in a wedding attended by Tony Blair and Silvio Berlusconi,20 before retiring from politics in 2002. Antonio López-Istúriz White, another one of Aznar’s assistants, was appointed to replace Agag as general secretary of the EPP after his retirement, as well as executive secretary of the Christian Democrat International in October of 2002, positions he would hold for the next two decades. This period where Spain was the only major country with a right-wing government in power allowed the PP to become highly influential in these institutions, and shape their decisions. Moreover, the admission of Silvio Berlisconi’s Forza Italia into the EPP would not have been possible without the influence of the PP. This period of dominance made Spain the second major center of European conservatism besides Germany.

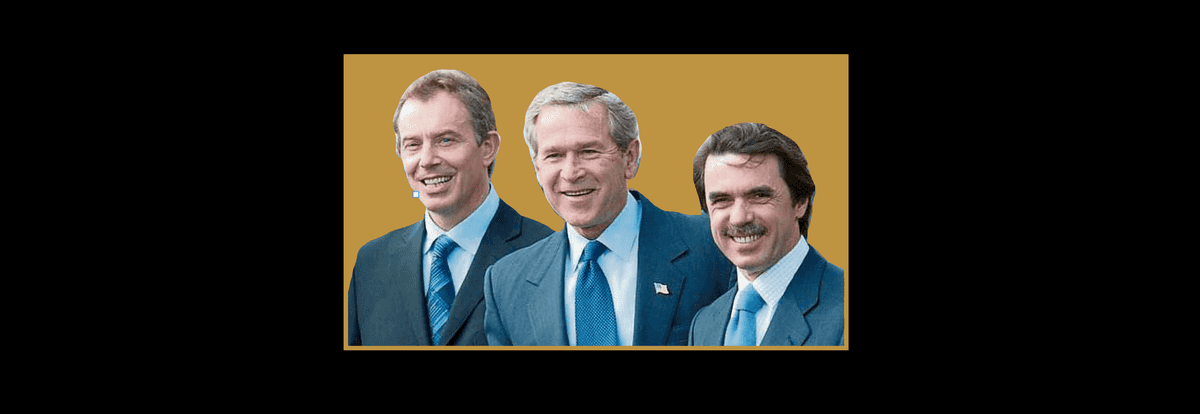

Shortly after Aznar achieved an absolute majority in the 2000 election, his ally President George W. Bush was also reelected in the United States.21 Seeking to deepen his relationship with the United States as a result of his deeply Atlanticist outlook, he was convinced to participate in the Iraq War by his defense advisor, Rafael Bardaji who helped plan the Azores meeting between Aznar, Bush, and Blair22 and Aznar was the only major figure outside of the Anglosphere to back the invasion of Iraq.

Concerned how the Spanish public would react to the war, Aznar sought the support of Bush to help bolster reelection prospects, according to a leaked memo from February of 2003.23 24 Ultimately though, Aznar opted out of seeking reelection, supporting Mariano Rajoy as his replacement for the 2004 elections. And up until a few days before the election scheduled for March 14, the PP felt certain that they were going to win the election, with public polling either showing them with an outright majority or likely to be able to form a minority government with the support of regional right-wing parties.

Then on March 11, 2004, at 7:37, the first of a series of bombs was set off on the Madrid commuter lines.

The Madrid Train Bombing: 193 died and Aznar lied about why

The terrorist attacks on March 11, 2003, popularly known in Spain as 11M, became the biggest mass casualty event in Spain since the Spanish Civil War: 193 died and over two thousand were injured. The immediate reaction of the incumbent PP-led government was to blame the attack on ETA, a leftist-basque separatist organization which had been waging a guerilla campaign against the Spanish government for nearly half a century at the time. Indeed, it seemed entirely plausible, and this was echoed by politicians from the opposition PSOE.

By 3:00 PM, police sources indicated that the attack was likely committed by Islamists,25 and by the evening there was mounting evidence that this did not follow the typical modus operandi of ETA. Despite this, the Minister of Foreign Affairs ordered the diplomatic staff of the country to state otherwise.26 Statements released by President George W. Bush and the United Nations Security Council echoed this certainty. The reason why the government was so insistent on it being ETA can be summed up by the quote attributed to two close advisors to Aznar, “Si ha sido ETA nos salimos del mapa, pero si han sido los yihadistas, nos vamos a casa” (“If it was ETA we went off the map, but if it was the jihadists, we went home”).27

By the morning of March 12, El Mundo and other outlets began to publish reports indicating that the attacks were likely by Islamists.28 Aznar called for protests this day as a show of strength against the terrorists, with the opposition PSOE joining in on the marches. The Madrid march was also joined by Silvio Berlusconi of Italy, Jean-Pierre Raffarin of France, and José Manuel Durao Barroso of Portugal,29 three important allies of Aznar within the EPP. During the march, protesters in Barcelona attacked the deputy prime minister for being complicit in the attacks. And that evening, ETA officially denied responsibility, to which the interior minister simply responded “No nos lo creemos" (We don't believe it).

Campaigning on the day before the election is illegal in Spain, as it is considered a day of reflection. News reporting is highly restricted from midnight on the day before the election until the polls close. Yet the conservative newspaper El Mundo published an interview where the PP’s presidential candidate, Mariano Rajoy, once again asserted that ETA had committed the attacks. Government spokespersons continued to confirm this line, saying that ETA continued to be the primary line of investigation.30

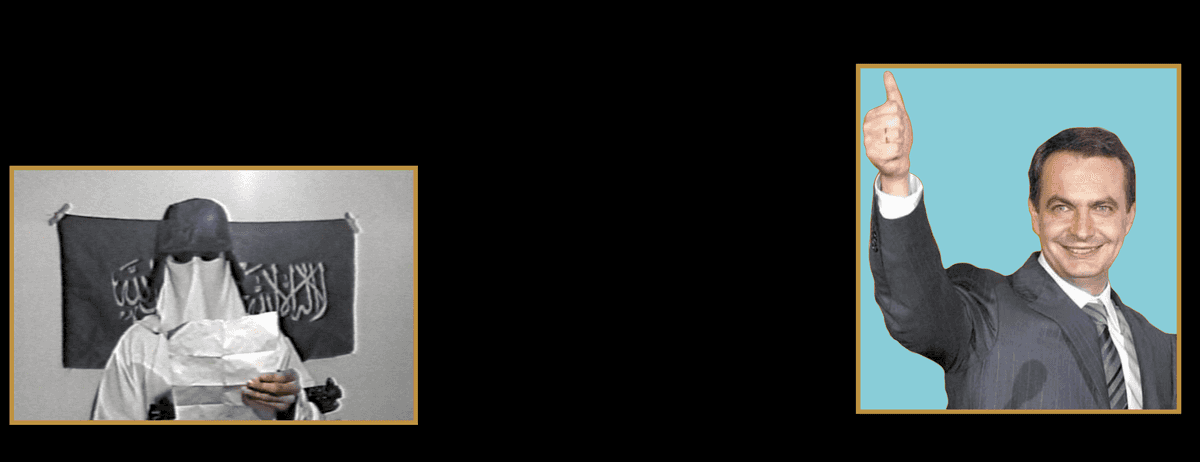

The government considered recalling congress and declaring a state of emergency, which would lead to the postponement of elections. Protesters began appearing outside of the Madrid headquarters of the PP, which Rajoy accused of being illegal and illegitimate, and, without evidence, accused of being organized by other unnamed political parties.31 These protesters were joined by others from across Spain.32 Just after midnight, in the early hours of the 14th, the day of the election, Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for the attack. Around the same time, Aznar decided to let the elections go ahead. His party would go on to be defeated in what they believed to be an electoral upset, with the opposition PSOE taking control of the government with José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero as prime minister.

El Mundo and the Spanish proto-QAnon

Within a little over a month, the conservative newspaper El Mundo, began to publish stories that questioned the official narrative around 11M. By June, even before the official parliamentary investigation began, El Mundo began to allege that the bombing had been part of a plot by the Spanish police. By August, the “Peones Negros” group began to protest the official government story, protesting and calling for the resignation of prime minister Zapatero.33 These protests were later joined by the Asociación de Víctimas del Terrorismo (AVT) and Confederación Española de Policías (CEP). In November of 2004, former prime minister Aznar stated that attackers aimed to “overturn the electoral result", and change "the parliamentary majority". He further said, "If the elections, instead of being called for March 14, had been called for March 7, then the attacks would have been on March 4."34

These protest movements continued to grow over the next few years, with the rhetoric growing more extreme. El Mundo paid one of the people convicted for the bombings for a story where he claimed that Zapatero had committed a coup d’état against the government.35 The explanations ranged from ETA involvement to the Moroccan government, to even the PSOE committing the attacks as part of a dirty war. While the identity of the attackers themselves differed, the general story was that it was a staged attack by opponents of the incumbent government meant to damage its chances in the election with the tacit support of the security services. The PP would often collaborate with groups associated with the Peones Negros, and would organize marches with groups like the ATV.36 37

Ultimately, the investigation into the 11M bombings by the Spanish Congress failed to reach a unanimous conclusion because of a lack of agreement with the opposition PP. Even the sentencing of the bombers failed to subside the conspiracy theories until the PP was returned to power.

While future PP leaders would attempt to distance themselves from the conspiracies, it should be emphasized how influential these protests were in building the modern Spanish right. In a sop to the conspiratorial wing of the party, the next PP government would appoint a special prosecutor to investigate claims of attempts to conceal evidence from the wreckage of one of the trains. A future PP leader, Pablo Casado, mentored by Aznar, would imply there were still questions 15 years after the bombing.38 39 40 41

Rajoy and Aznar abroad

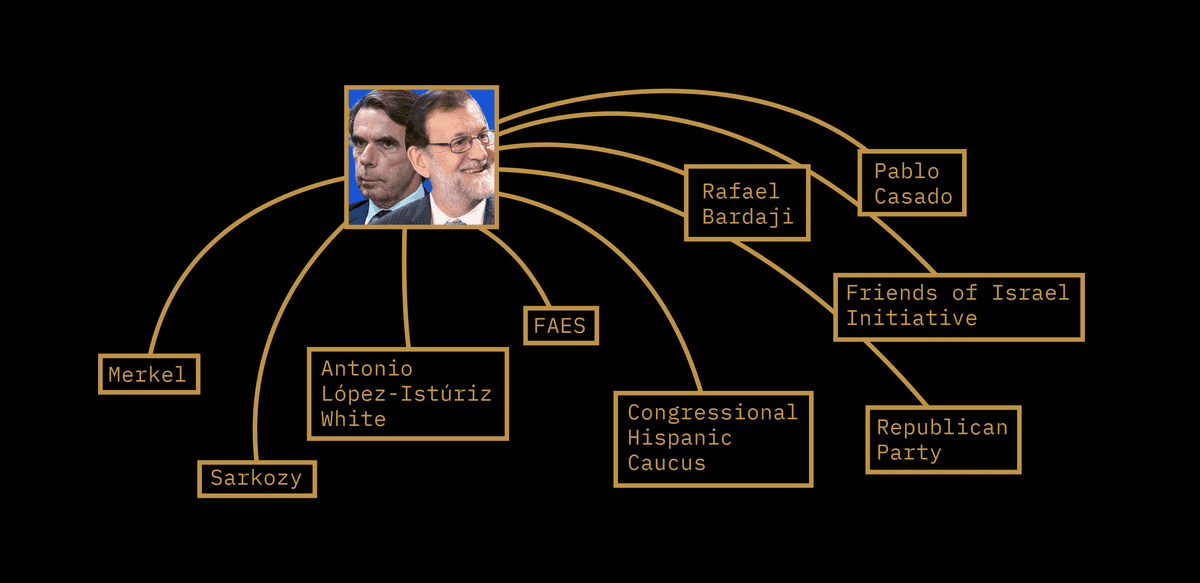

Rajoy was initially seen as the continuity candidate for Aznar, and their relationship remained strong throughout this period.42 Although he maintained connections with various parties and leaders, Aznar primarily focused on combating the pink tide in South America through his FAES foundation.43 He also campaigned for Felipe Calderon ahead of the 2006 election even though it may have violated Mexican electoral law.44 In the United States, he maintained a cordial relationship with the Republican Party and he primarily worked with the Congressional Hispanic Caucus. Higher-level relationships in the United States were primarily maintained by people like Rafael Bardaji and Antonio López-Istúriz White. But during the Obama era, Aznar founded the “Friends of Israel Initiative” with Bardaji and Pablo Casado. Bardaji and Aznar would even visit and speak at zionist synagogues46 in the United States maintaining strong links with the Zionist right.

Domestically, Rajoy remained focused on attempts to unseat the incumbent PSOE government. They used their connections with Antonio López-Istúriz White to have Merkel and Sarkozy campaign for the PP ahead of the 2008 elections.47 Furthermore, the PP campaigned on the fact that the Spanish government maintained relationships with various pink tide governments. But although there were initial hopes that the PP could regain the presidency with the support of regionalist parties, the PP were unable to unseat the government in the 2008 election.

In the aftermath, Rajoy pivoted away from his relationship with Aznar, trying to develop a more centrist profile. A spokesperson for the PP claimed after the 2008 American election that Obama would “vote for the PP” if he lived in Spain.48 Antonio López-Istúriz White, head of the EPP during this period, would attend both the Democratic and Republican national conventions. During Rajoy’s presidency of the PP, the party would even go on to hire ex-Obama campaign manager Jim Messina to manage Rajoy’s 2016 reelection campaign. The collapse of the global economy contributed to the PP's victory in the 2011 Spanish elections, which resulted in a cratering of the government's popularity.

HazteOir, El Yunque, and the 2014 European Elections

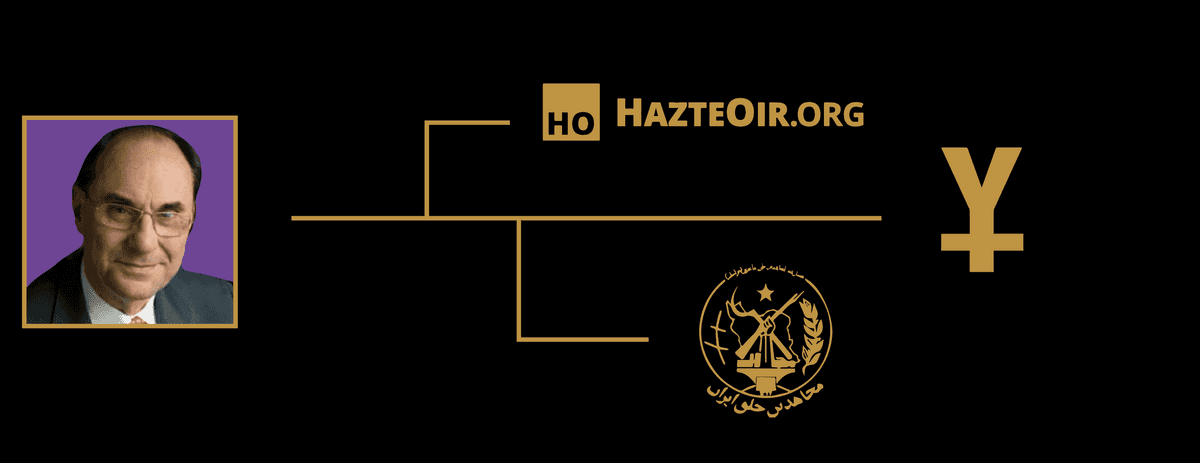

The move towards the alienation from the PP led to the foundation of a new political party, VOX. Most of its leadership consisted of former PP members. It was initially led by Alejo Vidal-Quadras Roca, a member of the European Parliament with the PP known for his hardline stance against regional nationalism among Catalans49 and the Basque Country50. The new party received an initial 800,000 euros in illegal seed funding from the People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran (MEK), an idiosyncratic cult and opposition group to the Iranian government.51 The organization, which is primarily funded by Saudi Arabia52 sought to support Vidal-Quadras, a longtime ally of theirs in the European parliament.53 The party was further supported by HazteOir (now known as CitizenGo), a Spanish organization linked with the far-right Mexican paramilitary organization, El Yunque.54 55 HazteOir affiliated donations provided56 an additional 300,000 euros for their European election campaign.

As the European elections approached, Rajoy’s PP was quickly dropping in the polls as a result of its implementation of harsh austerity measures. The PP dropped from 45% to 30% in public polling within a little over a year in government. However, the PSOE was unable to benefit from the PP’s unpopularity, as it was still seen as largely to blame for the recession. While in the 2009 European election, Spain had six parties represented in the European Parliament, with the PSOE and PP obtaining 87% of the seats, this combined total dropped to just 55% for the 2014 European election, with several new parties achieving mandates.

The election marked a massive rebuke for the two traditional parties, and it is speculated to be the primary driver behind the resignation of King Juan Carlos in 2014. On the left, the anti-austerity Podemos achieved results far outperforming expectations. On the right, there is Ciudadanos, a national liberal and unionist party with its first president, Albert Rivera, who was a former PP activist. Alejo Vidal-Quadras Roca’s VOX failed to distinguish itself from the other unionist party, and it resulted in Santiago Abascal, who represented the extreme right of the party, taking over VOX’s leadership with the support of HazteOir.

The election signaled the end of Spain’s two-party system, which led to significant interest in the country by Europarties. VOX was unable to gain any momentum during this period, running in both the 2015 regional elections, 2015 general elections, 2016 general elections, and the 2016 Basque elections, getting less than 0.5% of the vote in each contest. Yet despite constant elections, no governing majority could be found in the Spanish parliament. It was only with the abstention of the PSOE in Rajoy’s investiture that a third election was avoided. This collaboration between the PSOE and PP infuriated the Spanish right, with Bardaji calling for an end to Rajoy’s leadership of the PP.57 The Rajoy government continued to limp on for the next several years, but this caused increasing anger and dissatisfaction with the PP among the traditional Spanish conservative base.

Bardaji, Catalonia the Rebirth of VOX

In the aftermath of the European elections, Abascal’s VOX party struggled to gain attention. While the party did develop some contacts with the radical right Le Pen and AfD,59 it was a marginal force. El Yunque continued to be influential within the party with CitizenGo/HazteOir helping cultivate members for VOX59 and offering support during electoral campaigns.60 The head of HazteOir joined the board of the World Congress of Families during this time, an anti-LGBT61 hate group that helped defend the “anti-LGBT propaganda” laws. HazteOir began pushing transphobic messages during this period,62 and this rhetoric was reflected in public statements given against gay marriage and abortion by Abascal.63 64

During this period, VOX began to absorb people from various post-Francoist parties such as FET y de las JONS.65 It first gained significant traction during the Catalonia crisis, where it accused the PP of betraying Spain to the separatists66 and this saw it gain a significant increase in membership as a result.67 This allowed the party to establish itself as the representation of the uncompromising Spanish right. It is within this context that the party began to see significant defection from those dissatisfied with the PP.

Bardaji left the PP and joined the party executive in VOX68 helping boost the party’s election prospects. VOX began to regularly appear in Spanish polling, achieving a few percentage points and it was predicted that they would get a handful of MPs. Bardaji was able to bring on Israeli spin doctors associated with Neteyanhu to help run the party’s electoral campaigns,69 supplementing the existing operation by HazteOir. Despite VOX having several members from the virulent antisemitic El Yunque movement,70 as a founding member of the Friends of Israel Initiative, Bardaji was likely able to allay fears. In fact, Bardaji has explicitly argued for an alliance between Israel and the New Right,71 despite the fact they have historically flirted with antisemitism.72 During later electoral campaigns, there was also significant social media manipulation that benefited VOX,73 and while it is unclear who funded these campaigns, Bardaji’s connections are the most likely suspect.

VOX received a further boost with Rajoy being removed from power in a deal between the PSOE, Podemos, and various regional parties, including separatists. It is of some irony that the leader of the PP who replaced him, Pablo Casado, a protege of Aznar, worked together with Bardaji in FAES and the Friends of Israel Initiative. Casado’s leadership of the PP marked an initial move back to the right, with him promising to repeal abortion laws and defend Francoist monuments.74 Additionally, he made a promise to never work with regional separatist parties, something that appealed to the nationalist elements within Ciudadanos and the emerging VOX.

The leadership of both Bardaji and Casado were tested ahead of the Andalucian regional elections in December 2018. And despite polling that indicated VOX would maybe achieve one or two seats, the party far outperformed expectations. VOX achieved 11% in the polls and 12 mandates in the regional parliament. While the PP did significantly better, achieving 20% of the vote and 26 MPs, it only performed 2% better than Ciudadanos. This was the worst result for the PP since the 1982 election in Andalucia. Interestingly, 72% of VOX voters in Andalucia were men,75 with the strongest indicator of support for the party being opposition to feminism.76

Scholars had long talked about the Spanish exception, where the country seemed immune to the far-right, yet now VOX held the keys to the formation of the next Andalusian government. This is notable because Andalucia had long been considered a stronghold for the left, with the PSOE dominating the regional parliament since its creation in 1982, with this being the first-ever government not formed by the PSOE. Against the backdrop of Marie Le Pen77 and former leader of the Ku Klux Klan, David Duke,78 congratulating VOX on its victory, the party negotiated a supply and confidence agreement with the PP and Ciudadanos. VOX, a marginal party just a few months earlier, now seemed like it could be the kingmaker in the next Spanish national election.

The Building of VOX’s alliances with America and Europe

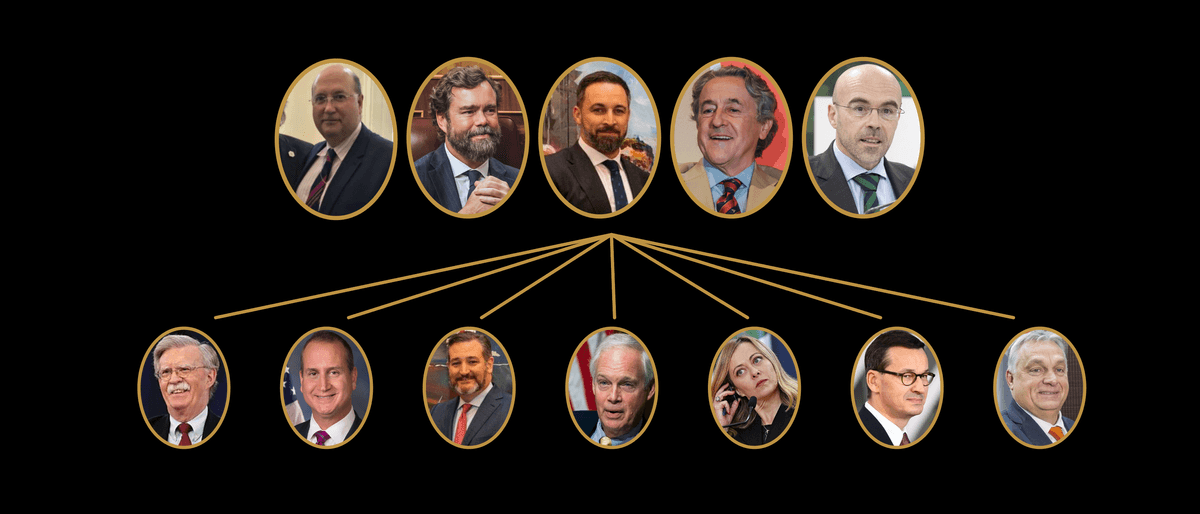

Rafael Bardaji met with US National Security Advisor John Bolton just a few days after the Andalucian elections.79 A few months later in March of 2019 VOX’s head of international relations, Iván Espinosa de los Monteros, visited CPAC80 before meeting with Trump officials and Spanish American donors.81 Iván Espinosa de los Monteros and Rafael Bardaji worked to develop relationships with the Anglosphere, and in particular with the American Republican Party. Within Europe, Hermann Tertsch and Jorge Buxale worked to develop networks with European right-wing parties, with VOX affiliating with the European Conservatives and Reformists after their 2019 European elections.

After an initial contact in 2019, VOX leader Santiago Abascal traveled to the United States in early 2020. During this trip, he met with American Senator Ted Cruz and Ron Johnson. Additionally, Iván Espinosa de los Monteros met with Mario Díaz-Balart, a Republican from Florida with a great deal of influence among the Cuban and Venezuelan exile communities. This is also notable because Mario Diaz-Balart’s brother, Lincoln Diaz Balart, had historically had a close relationship with Aznar, and they worked together to combat the Pink Tide in Latin America. This trip also saw them meeting with figures from the International Republican Institute, which was set up to help provide campaign assistance to ideologically similar parties as the US Republican Party and may be the source of the various American consultants involved in VOX networks.

Abascal also met with the Heritage Foundation, and one of its fellows would later go on to claim that “VOX is a party where Senators Mike Lee, Ted Cruz, Tom Cotton and Marco Rubio would feel right at home.”82 Given the Heritage Foundation’s role as a major source of staffing in Republican administrations, the next Republican administration will likely be much more favorable to VOX. These relationships have only since deepened, culminating in former president Donald Trump sending a video message to the party’s 2022 Viva conference.83 VOX also supported Trump’s claims of fraud during the 2020 elections.85 86 87 With Senator Ted Cruz continuing to regularly meet with VOX affiliated groups and the president of the powerful Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) proclaiming Abascal to be the “future prime minister” of Spain,88 VOX’s influence among the right in Washington is near complete.

Before VOX entered the European parliament, the party flirted with the idea of joining Le Pen’s political grouping in the European parliament if elected,89 and maintained cordial relationships with Italy’s Salvini90 and the far-right Chega91 in Portugal. However, VOX sought to distance itself from the furthest right-wing elements within Europe and moved towards joining the ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists).92 Abascal traveled to Poland to meet with the biggest party in the ECR, Law and Justice, in March of 201993 and ultimately joined the group after being elected to the European Parliament. Georgia Meloni even campaigned for the party in Andalucia ahead of the 2022 election,94 and spoke at the party’s conference in 2022 along with Polish Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki and Hungarian Prime Minister, Victor Orban.95

In contrast, the PP lost significant influence abroad. With the United States, Pablo Casado attempted to maintain good relations with both the Republican and Democratic Republican Party.96 However, given the radicalization of the American right, congratulating President Joe Biden on his victory97 will get you little support.

The Collapse of the Center

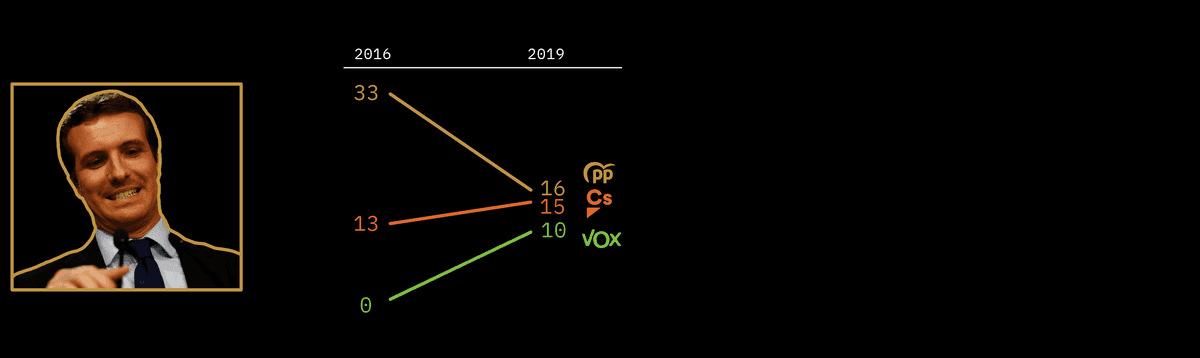

After the Andalucian election, the PP now had VOX as its ideological competition on the right. Initially, Casado decided to double down on his strategy of trying to reclaim Aznarismo, campaigning as a right-winger ahead of the April 2019 elections98 in Spain in an attempt to stem the rise of VOX. However, this failed spectacularly, with the party once again reaching its worst result since the 1980s, only achieving 66 MPs and being less than a percentage point ahead of Ciudadanos. Casado then shifted away from Aznarism, attempting to reclaim the center.99 100

The PP saw gains during November 2019 after a collapse in the vote of Ciudadanos, although the election also saw further defections from the PP to VOX given its shift towards the center. Consequently, VOX became the third largest party in the Spanish parliament, achieving 15% of the vote and a similar proportion of seats. Although Casado was unable to prevent the formation of a government between the PSOE and the Spanish left in the election’s aftermath, he did perform well enough to stabilize his presidency over the PP.

While VOX expanded its reach internationally in the aftermath of the 2019 elections, Casado focused on attempts to consolidate the political center. His party at first attempted to create a temporary electoral alliance between itself and Ciudadanos,101 before shifting to a merger of the parties, or a permanent electoral coalition.102 Therefore, Ciudadanos attempted to distance itself from the PP, but after it attempted to elect the PSOE candidate as regional leader in Murcia, several of its regional MPs defected to the PP. When they attempted to do the same in Madrid, the regional president, Isabel Diaz Ayuso of the PP called early elections, where she absorbed most of the former Ciudadanos voters and was elected as regional president with the support of VOX.

However, this presented Casado with a dilemma. Although it was increasingly clear that the PP would need a pact with VOX to govern, Casado had advocated against such an alliance. The right-wing of the PP no longer trusted Casado after his shift towards the center following the April 2019 elections, but the more liberal wing of the party remained skeptical of a pact with VOX.103 Ironically, such a strong showing in Madrid helped undermine his control of the PP. Casado attempted to relaunch his leadership once again, proposing a tour “against populism” in South America104 while working with organizations associated with the liberal sector of the PP, such as the IDC, whose secretary was Antonio López-Istúriz White.105 To relaunch his presidency, however, he would need an electoral victory and pushed for early elections in the PP stronghold of Castilla y Leon.

However, Casado failed to achieve an absolute majority as had been hoped106 with VOX achieving a strong showing and demanding entrance into regional government to support the presidency of the PP. As a result, Casado quickly lost support within the PP, being replaced by Alberto Nunez Feijoo as president.

Unlike Casado, Feijoo supported bringing VOX into government,107 with the coalition government between the PP and VOX being inaugurated shortly after Feijoo took control of the former. Feijoo’s assumption of the presidency marked a shift away from centrism within the PP. He also supported the removal of López-Istúriz as head of the EPP, who was then replaced by Manfred Weber of the German CSU.108 Like Feijoo, Weber has advocated for alliances between the traditional and far right for member parties of the EPP on a national level,109 supporting the Castilla y Leon Pact.110 Feijoo’ and Weber’s trip to South America demonstrated this change.111 While just a year earlier Casado advocated for parties in South America to confront the far right, Feijoo and Weber met with parties who advocated for their inclusion, such as Sebastian Pinera’s Chile Vamos alliance, and Macri of Argentina.

The PP’s moderate sector had been marginalized, and it was clear that the next Spanish election would be between two blocs with two potential outcomes, a continuation of the current coalition government, or a new coalition government between the PP and VOX.

Foro Madrid

Meanwhile, VOX continued to pour resources into its Foro Madrid project, and its influence in South America continued to expand.

VOX’s first contacts with the South American right emerged in 2019, when Abascal met with Antonio Kast, leader of the Chilean Republican Party, in Spain.112 Kast was already deeply linked with El Yunque networks within the country.113 But with the party’s focus on national elections in 2019, it spent little time trying to expand its network. It was only with the inauguration of the coalition between the PSOE and the Spanish left in 2020 that the party shifted towards building its South American networks. Hermann Tertsch and Victor Gonzales visited the putschist government in Bolivia in January 2020, both to support the coup and to undermine the new coalition government by claiming that Morales financed Podemos.114 They took a second trip to Ecuador in March of 2020, seeking to prove both that Podemos had been funded by foreign sources and to undermine the leftist former president of Ecuador, Rafael Correa.115 And it was a short time afterwards that Foro Madrid was first mentioned by Abascal during his meeting with the head of the Organization of American States (OAS) in March of 2020.116 Although it has been planned to launch in June of 2020, the pandemic delayed its launch until October, when it was launched virtually.

Based on VOX’s existing networks, at the start, there were only about 50 signatures from American, European, and South American conservatives and reactionaries.117 But through the continued networking of VOX in South America, the network has subsequently expanded. It now includes the president of Argentina, Javier Milei and ex-Paraguayan president Horacio Manuel Cartes Jara. Additionally, the former president of Colombia, Alvaro Uribe has done events with the Foro,118 and VOX claimed that former Ecuadorian president Guillermo Lasso was going to sign on after they met with him,119 something he has subsequently denied. The current leading candidate of the Venezuelan opposition, Maria Corina Machado has signed onto the project, along with various figures from the Fujimorist right in Peru, the Cuban opposition, and members of the coup government in Bolivia.

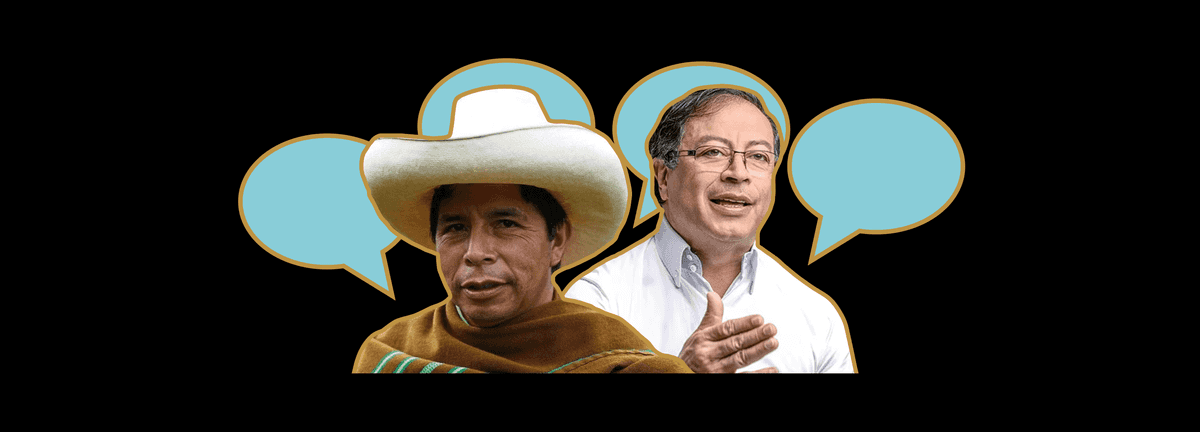

However, its most important impact has been its ability to create and mobilize a network among the far-right in Latin America, to undermine left wing governments in the region. The organization has held several events in South America, seeking to influence the outcome of political races, such as when it held an event in Colombia ahead of its 2022 elections. Among claims of the delegation, it stated that narco-traffickers and the Venezuelan government were attempting to steal the upcoming election, that Honduras and Chile had fallen under the sway of “Castro-communism”, and that there was an international campaign to undermine Jair Bolsonaro.120

Once Gustavo Petro won the presidential election in Colombia, its network amplified claims that the election was stolen by the left,121 and members of the Foro Madrid have also claimed fraud during the Peruvian elections.122 One of the signatories of the Madrid Charter, Eduardo Bolsonaro, later went on to participate in the coup attempt in Brazil after Lula’s victory. And although the organization nominally condemned the violence, it spent the vast majority of its statement attacking the left, and claiming that the governments of Colombia, Chile, and Bolivia were illegitimate because of social movement protests preceding their elections.123

The organization then went on to organize a conference in Peru in March of 2023 as part of an effort to prevent early elections from being called in the country. During the 2023 Ecuadorian elections, it claimed, without evidence, that the candidate of the left, Luisa González, was supported by narco-traffickers.124 Regardless of sending electoral observers for the Guatemalan election and indicating that the election had been run cleanly,125 newspapers controlled by the foundation have gone on to falsely amplify claims against President Bernardo Arevalo.126

The Foro Madrid now serves as one of the primary networks for attacks against left wing governments and social movements in Latin America, and it continues to expand its network. Having met with a newly founded far-right party in the Dominican Republic ahead of the 2024 elections,127 it could play a major role in helping the party enter parliament. Furthermore, it could play a major role in amplifying claims of fraud in the upcoming Mexican and Uruguayan elections, especially given that polling predicts victories for parties associated with the São Paulo Forum.

The Internationalization of the 2023 Spanish General Elections

While every general election has important societal and economic consequences, it is rare for a singular election to have an impact on international political alliances. Yet, that is exactly what was anticipated from the 2023 Spanish general elections. For both VOX and the PP, it would mean the possibility of entering the national government. But a strong showing for VOX would strengthen the ECR’s influence over the European Commission, and a Spanish government that would openly campaign against leftist governments in Latin America. For the PP, it meant the possibility of reasserting its role within the EPP, which had been significantly weakened while it had been in opposition. It is why Georgia Meloni, also of the ECR, campaigned for VOX in Andalucia during its elections128 as well as directly claiming that her victory in the Italian elections could lead to VOX coming to power.129

While VOX did have a strong showing during the Andalucian elections, it further strengthened the PP, with the party achieving an absolute majority in the regional parliament for the first time in the party’s history. A victory for Feijoo was important for the EPP given it was not a governing member of any major European country.130 Further regional elections in May of 2023 saw the PP and VOX taking control over the vast majority of regional parliaments.

These results prompted the government to call early elections, with there being a broad sense that the victory of the right was inevitable, and the election was simply about stemming losses. The EPP backed Feijoo, moving its summit to Spain,131 defending the alliances with the far right132 and attacking a European commissioner when he criticized the PP’s Andalucian policy.133 They even went so far as to claim that the European Commission was campaigning for Sanchez.134 For VOX, they once again received the endorsement of Meloni, but additionally used their connections from the Foro Madrid to get endorsement videos from right-wing politicians including,135 far-right Chilean presidential candidate, José Antonio Kast;136 leader of the Colombian right, María Fernanda Cabal;137 and member of Honduran opposition Eder Mejia.138

The party additionally mobilized the ECR to support its campaign, with Meloni139 campaigning in the days before the vote. Additionally, the party likely had American consultants working on the campaign through Bardaji, but at a minimum, they were so inspired by Trumpism that they decided to plagiarize “Latinos por Trump,” simply swapping it out, making it “Latinos por Abascal.”140

Finally election night came, and to the shock and dismay of both the PP and VOX, they fell six seats short of an absolute majority in parliament. Even when counting regional right-wing allies such as the Canaries coalition and the Navarrese People's Union, they were well short of a majority, and any hope for the presidency would require the support of nationalist parties, parties whose agreements with the PP were a large motivation behind the founding of VOX. The right had lost.

This led to a scramble to find a way to allow Feijoo to become president of Spain. Manfred Weber initially called for a grand coalition between the PSOE and PP, with Feijoo as the president.141 This was a huge headache for the EPP, given how much they were depending on the PP to grant the party influence at the European Council.142 The incumbent PSOE-Spanish left government ignored this proposal, and it began to negotiate with various regional partners to form a government. And despite opposition from VOX, the PP frantically attempted to find a regional nationalist party that would tolerate the participation of VOX in government. However, despite extremely generous offers to the Basque Nationalist Party, no formula could be found and the parties all settled for negotiations with the PSOE and the Spanish left.143 144 145

The Internationalization of the Amnesty Deal

The Amnesty Deal for investiture was quite simple: In return for a pardon for various participants in the 2017 Catalonian independence referendum, Junts per Catalunya would support the investiture of the government. The biggest piece of this reform would be a move to reduce the politicization of the judiciary, which was dominated by conservative judges, a legacy of the Franco regime.146

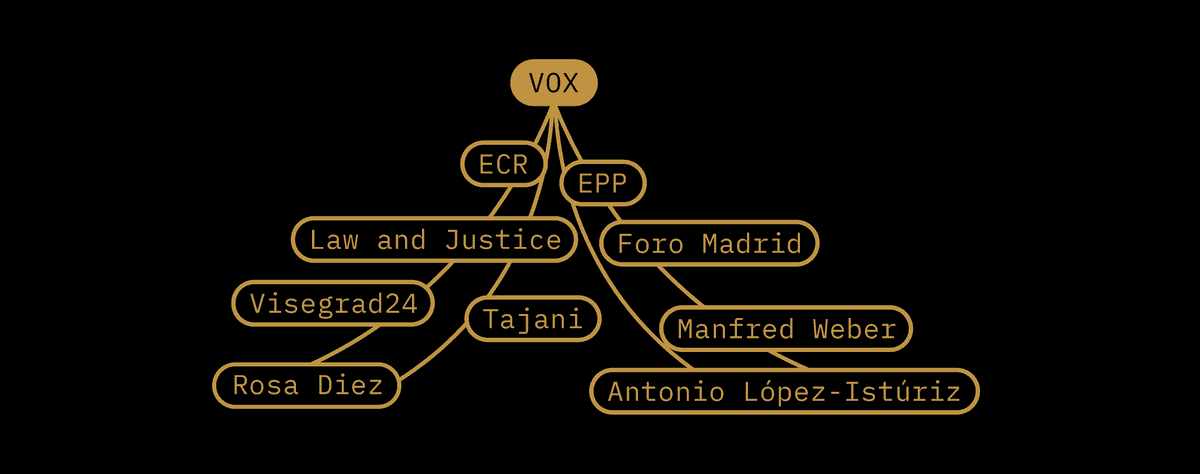

To block the investiture from going through, VOX attempted to mobilize its international connections to push forward the narrative that the deal was illegal. It published a video in English by one of its MPs147 and had Santiago Abascal sit down with former Fox News host, Tucker Carlson, for an interview about the amnesty law.148 This helped spark interest among the far-right anglosphere about the protest149 with far-right influencer Jack Posobiec even going as far as to openly support Francoism.150

VOX also used its connections to the ECR to mobilize against the deal. Visegrad24, a Twitter account supported by the Polish Law and Justice Party through government funds151 mobilized against the amnesty law.152 It helped push forward a claim that the assassination attempt against former VOX leader Alejo Vidal-Quadras Roca was related to Amnesty Deal.153 Georgia Meloni, declared her support for Abascal when he visited the country a few days after the vote on the amnesty law154 which was followed by a second visit in December.155 Antonio Tajani, the Foreign Minister of Italy and member of the European People’s Party, further went on to claim that the Spanish government was controlled by the far left.156 The Foro Madrid, while simultaneously attempting to claim that the President of Colombia has lost his mandate157 and because of the loss of the midterm elections, refused to accept the deal supported by the majority of the Spanish parliament. Abascal event went as far as to call for Sanchez to be hanged, during an interview he gave as part of his trip to the inauguration of Javier Milei.158

However, the biggest push against the amnesty law was at the European level. Given how important Spain was to the parliamentary right in the European Union, the EPP and ECR moved to find ways to block the law through European institutions, attempting to prevent the pact from happening. Manfred Weber called on the European Commission to block the law, falsely claiming that this violated the rule of law principles in the European Union as part of an attempt to force new elections.159 This move was backed by Abascal.160

The EPP has even gone so far as to claim that Spain could use access to European funding as a result of the amnesty law161 with the Vice President of the EPP claiming that Sanchez was the “Orban of the South”.162 163 Manfred Weber further stated that Sanchez should be disallowed from any future positions in the European Union as a result of the amnesty pact.164 The European Justice Commissioner, a former member of the liberal ALDE grouping which has also been campaigning against the law due to pressure from one of its largest member parties, Ciudadanos, did express concern for the law, but failed to vocalize any specifics.165

This push for internationalization resulted in contentious debates in the European Parliament, with the liberal group Renew, the EPP, the ECR, and the radical right calling for a debate on the bill in the European Parliament.166 This debate saw the Socialists, Greens, and Left in parliament supporting the bill, EPP and ALDE claiming that this was no different than what was happening in Hungary, and far-right forces attempting to claim that the rule of law issue was entirely made up, to begin with.167 This was followed by Sanchez attending the European Parliament in December as part of his role as President of the Council of Europe. This debate became so heated that Antonio López-Istúriz White is facing possible sanction for anti-Sanchez slurs.168 169

Efforts continue on a European level to undermine the amnesty deal, most recently with former Spanish MEP Rosa Diez170 launching a petition asking for a review of the law. Since the initiative lies with the European Commission, action by the European Union is unlikely at least until the European Elections in June of 2024, in which the Spanish right is so focused on performing well. In the meantime, they are mobilizing against the law by taking to the streets.

Ferraz Protests

Even though Feijoo had considered a pardon for himself just a few months earlier, as news of an agreement between the government and Junts began to leak, the Spanish right called for mass rallies against the amnesty, claiming that any deal would violate the rule of law. Feijoo, Rajoy, and Aznar all participated together in one of these rallies171 marking the first time they were seen they had been seen together in public for many years.

Mass demonstrations continued throughout October as the amnesty was negotiated, with the PP being joined by VOX172 and the remnants of Ciudadanos. Its former leader, Albert Rivera, spoke out publicly against the pardon.173 The amnesty law also marked the first time since the 2014 crisis that there was such broad consensus on the Spanish right regarding a specific issue. As the negotiations continued into November, day protests in town squares were followed by night protests in front of the national headquarters of the PSOE, on Ferraz Street, where the pact was being negotiated. Juan García Gallardo, regional head of VOX in Castilla y Leon, called for protesters to gather in front of the PSOE headquarters to protest the amnesty agreement174 and these protests were eventually joined by Tucker Carlson and Santiago Abascal.175 Additionally, HazteOir, VOX’s unofficial campaign arm, made an appearance176 and protesters began to appear in front of the various offices of the PSOE throughout Spain.177

As the protests continued, the “National November” movement was created to help coordinate them. In addition to receiving the official endorsement of VOX,179 the movement was also supported by youth organizations with institutional links to the party, such as Revuelta.180 Additionally, many figures from the extra-parliamentary far-right joined in on the protests. These include the French Rassemblement National inspired National Democracy and the post-Francoist successor party FE de las JONS.181 The Workers Front, a nominally Marxist-Leninist organization known for their opposition to immigration, Islam, and support for Hispanic identity also participated in the protests.182

Virtually every minor far-right party in Spain announced its official support for National November or the protests, and a Nazi flag was flown during the protests without pushback.183 Several colorful characters appeared during the protests such as Captain Spain, a far-right influencer known for dressing up in a Captain America costume with Spanish colors and Marina Seren, a far-right former UFOologist who was radicalized into Nazism and who claims to be the reincarnation of the Nazi commando Otto Skorzeny.184 Also seen participating in this movement was María Isabel Medina Peralta, the daughter of a PP mayor who was banned from entering Germany after attempting to intern with the neo-Nazi “Third Path” political party.185

The VOX-associated figures and the extreme anti-democratic right were freely able to intermingle at the protests. Consequently, many were then interviewed and were able to broadcast their far-right message through various newspapers and journalists sympathetic to the right.186 Despite the PP itself not technically participating, the former leader of the party in Madrid, Esperanza Aguirre, made an appearance at the protests.187

Conclusion

The Ferraz protests not only represented the largest mobilization of the Spanish right in decades but also demonstrated how interconnected the various factions of the right are within Spain. Parliamentary figures from the Liberal Ciudadanos, the conservative PP, and the far-right VOX would attend protests together in town squares during the day. Ciudadanos and the PP's official representatives would then go home at night and not openly support the more violent protests. However, it was evident that many of the same people who attended the protests during the day would also attend them through the night.

Figures associated with fringe aspects of the protests, such as Captain Spain, have been seen at various VOX events before Ferraz.188 And despite VOX officially denouncing aspects associated with the far right like racism and antisemitism, they are more than willing to endorse Holocaust deniers for parliament189 and attend the same protests as neo-Nazis. VOX will claim the police are suppressing their “peaceful protests”190 while they call for the hanging of President Sanchez after being inspired by effigies built by the right in Argentina.191 Yet when protests against the newly elected government in Argentina take place they will fully support the suppression of protesters by the Argentine police. VOX will claim that the amnesty law is a putsch while supporting putsch governments in Bolivia, and attempting to lay the groundwork to claim fraud if a left-wing party wins an election in South America.

The Ferraz protests show that the entirety of the spectrum of the Spanish right, from the liberal Ciudadanos to VOX, are united and in lockstep behind one idea: that the post-Franco regime was far too progressive.