CPAC Comes Calling in Hungary

On April 25, 2024, the Budapest-based Center for Fundamental Rights hosted the third edition Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC). The lineup included reactionaries such as Spain’s Santiago Abascal and Jack Posobiec, and panels such as "Wokebusters," "Sovereignty lives, globalism dies," and "Save the West, Protect the Borders" took place.

CPAC 2024 would be the third time Hungary has played host to a conference historically associated with the American right. Is consolidating reactionaries in Europe the only reason behind such a decision? Or has the Hungarian leadership realized that for its regime to survive, it must become the centre of a new reactionary international in the world?

Background

After World War II, Hungary’s communist government joined the Soviet Union’s military alliance, known as the Warsaw Pact, sitting on the westernmost edge of the communist bloc in Europe. In 1956, Hungary witnessed an uprising when citizens seeking to withdraw from the Soviet bloc briefly overthrew the country’s government. Ultimately, communist rule and Soviet alignment were reestablished in the form of a “Goulash Communism,” where economic control was relaxed.

Amid the final years of the USSR and its security alliances, the first post-communist elections in Hungary were scheduled in 1990. As a newly emerging post-Warsaw Pact state, the ideological profiles, societal support, and political characteristics of Hungary’s political parties were still in formation.1 It is within this context that the party representing the country’s youth and student activist movement, Fiatal Demokraták Szövetsége, or Fidesz, was elected to parliament.

Like most Hungarian political parties during this era, the Fidesz party was ideologically incoherent, except for a vague commitment to liberalism. The party received various forms of funding and support from George Soros, who had been lobbied by the US Ambassador in Hungary, Mark Palmer, in his attempt to bolster support for his post-communist projects in the country.2 Fidesz’s lead candidate was Viktor Orbán, who had returned from a Soros-funded Oxford scholarship in 1990 to contest elections. His campaign was funded through a mix of membership fees and support from foreign foundations.3

After the 1990 parliamentary election, Fidesz joined the Liberal International, along with its sister party, the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ). During this time, Orbán built a strong relationship with Liberal International’s chairman, Otto Graf Lambsdorf of the German Free Democratic Party (FDP), and was elected as Vice Chairman. He helped build himself an international profile by bringing the Liberal International conference to Budapest in 1993. Although both Fidesz and SZDSZ were part of the same international organization, this period also saw the ideological sorting of the two parties. As Orbán took control of Fidesz, and centralized the party around himself, he removed its left-liberal members. SZDSZ did the same with its conservative liberal members.

Ahead of the 1994 election, Orbán, now officially the leader of the party, worked with a small circle of advisors — including the Hungarian-born, Anglo-style political “spin doctor” András Wermer — to shift the party’s profile to the right. The party ended up performing worse than it did in 1990. Yet for Fidesz, this wasn’t entirely a failure: a coalition between the Hungarian Socialist Party and the SZDSZ created a vacuum on the Hungarian right, which Fidesz filled.

The Rise of Fidesz

In the aftermath of the 1994 election, on the suggestion of Wermer, Fidesz rebranded itself as the Magyar Polgári Párt or the Hungarian Civic Party.4

During this period, Orbán began to actively receive advice from organizations and figures based in the West, such as Sebastian Gorka, a British-born Hungarian who went on to work as a top advisor in the Trump administration. Perhaps two of the party’s most important supporters after the 1994 election were the International Republican Institute (IRI), closely linked with the US Republican Party, and US political advisor, Daniel Odescalchi.5

An American political consultant involved in numerous campaigns in the United States and abroad, Odescalchi previously worked as an advisor to the first post-communist Prime Minister József Antall from the conservative Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF). However, his relationship with the party broke down after Antall’s death in 1993.

Odescalchi remained involved in Hungarian politics regardless, working for the European People's Party (EPP)-associated Robert Schurman Institute, and founding the “Survival in a Democracy Project.” This project received backing from the IRI, several EPP-aligned parties, and the Westminster Foundation.6 These projects helped provide advice and consulting for the young Eastern European political parties, who had much to learn about including understanding the basics of campaigning, how to manage parliamentary constituent relations, and how to write a press release.7

Under the tutelage of Odescalchi, Fidesz grew from 20 to 148 MPs in the 1998 elections and became the new senior partner in a right-wing coalition. The government was formed in a three-way coalition between Fidesz, the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF), and the Independent Smallholders' Party (FKGP). While it would be incorrect to ascribe Fidesz’s victory in this election solely to the advice of consultants like Daniel Odescalchi, their impact drove the opposition Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) to subsequently seek out its own international consultants.

However, Fidesz failed to achieve re-election in 2002, falling six seats short of a parliamentary majority despite winning the popular vote. One constituency saw the Fidesz candidate lose by just two votes out of 34,220.8 This narrow victory was ascribed by Fidesz to the US-style door-to-door campaign of the MSZP. This type of campaigning remains rare outside of the Anglosphere but had been fully embraced by the then-Hungarian opposition. Fidesz would later work to replicate this campaign strategy.

The right protested the results of the election. Groups associated with the far-right Hungarian Justice and Life Party (MIÉP), led by István Csurka — now out of parliament — went to the streets demanding recounts. While Fidesz did not go that far, it did undermine the legitimacy of the results, with Orbán stating “We can’t be in opposition because the nation can’t be in opposition.”9 This spawned the "civic circles movements," and in the election’s aftermath, Fidesz revamped its political operation, employing US consultants. This includes Sean Tonner,10 a campaign consultant who had previously worked as an organizational director for Bob Dole's presidential campaign, among other roles. They assisted in implementing voter mobilization databases for their door-to-door efforts, setting the stage for future electoral success.

Despite this political reorganization, Fidesz failed to unseat the incumbent MSZP government in 2006. Despite some discontent on the right, rather than changing strategy, Fidesz doubled down. The party’s new director, Gábor Kubatov, continued to invest in the voter mobilization databases, leading to them becoming popularly known as the “Kubatov lists.”

How Orbán Changed Hungary

The publication of the Őszöd speech, where the MSZP Hungarian Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány went on a profanity-laden rant stating that his party lied about its accomplishments to achieve election in 2006,11 cratered the government's popularity, sparking protests from the right.

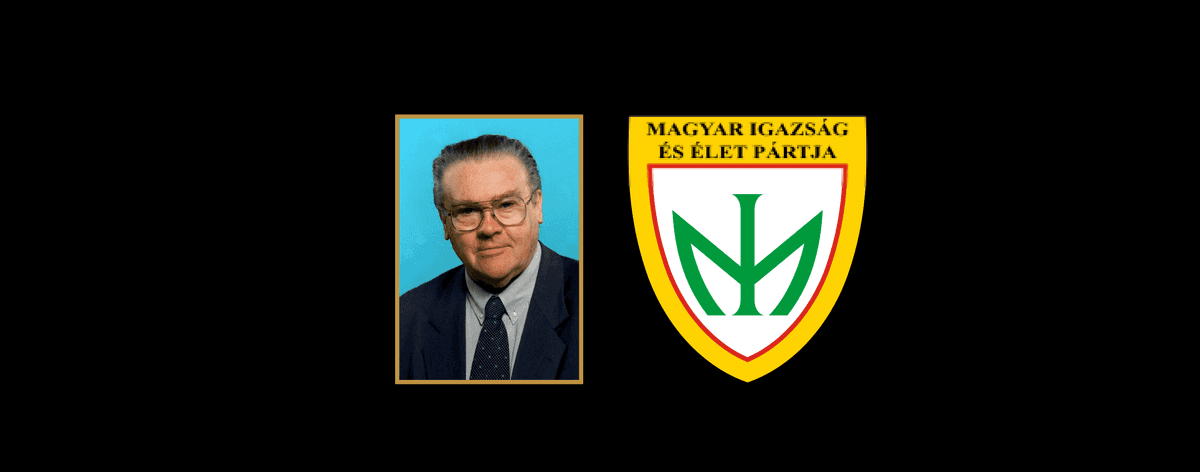

Yet the Fidesz campaign was not taking any chances, contracting numerous American consultants ahead of the 2010 parliamentary elections. The most important of these were the Republican consultants, Arthur J. Finkelstein and George Birnbaum, who had worked in the campaigns of both Ronald Reagan and Benjamin Netanyahu. They were contracted through Fidesz’s think-tank, the Századvég Foundation, starting around 2008, and were instrumental in recommending that Orban's campaign be against “the bureaucrats” and “foreign capital” in the context of a Hungarian society rocked by austerity and the 2008 financial crisis.12

Due to the Őszöd speech, the question was not if Fidesz would win, but rather by how much. The goal of Orbán was to obtain a two-thirds supermajority, which would allow his party to unilaterally institute constitutional changes. Come election day, Orbán was swept into power with 52.7% of the popular vote and 263/386 of the parliamentary mandates. With this new majority, a new constitution was drafted on Fidesz MEP József Szájer’s iPad13 and passed along a party-line vote after just nine days of debate.14 Despite alarms raised by international observers, Fidesz forced it through, intending to implement several changes designed to benefit Fidesz electorally.

To spin the future elections in his favour, the new constitution implemented several changes. The number of MPs was cut in half, with the opposition now facing new, larger constituencies that were gerrymandered to favour Fidesz.15 16 The two-round electoral system was reduced to just one, meaning that without a united opposition, Fidesz could easily dominate over half of MPs elected via single-member constituencies.

Furthermore, Orbán granted citizenship to thousands of ethnic Hungarians in bordering countries, such as Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine. And while Hungarians living further abroad had to travel in person and vote at an embassy, those living in nearby countries could simply vote by mail. Additionally, the Hungarian government spent millions of dollars courting these voters17 through the Bethlen Gabor Fund, funding everything from media to schools to football.18 Although voters abroad can technically only vote for the proportional national lists, the Hungarian state was more than happy to overlook the diaspora crossing the border on election day to illegally vote in constituency elections.19 These measures have made it exceedingly difficult to defeat Orbán through democratic means, allowing the party to repeatedly achieve supermajorities while hovering around 50% of the national vote.

A New Boogeyman

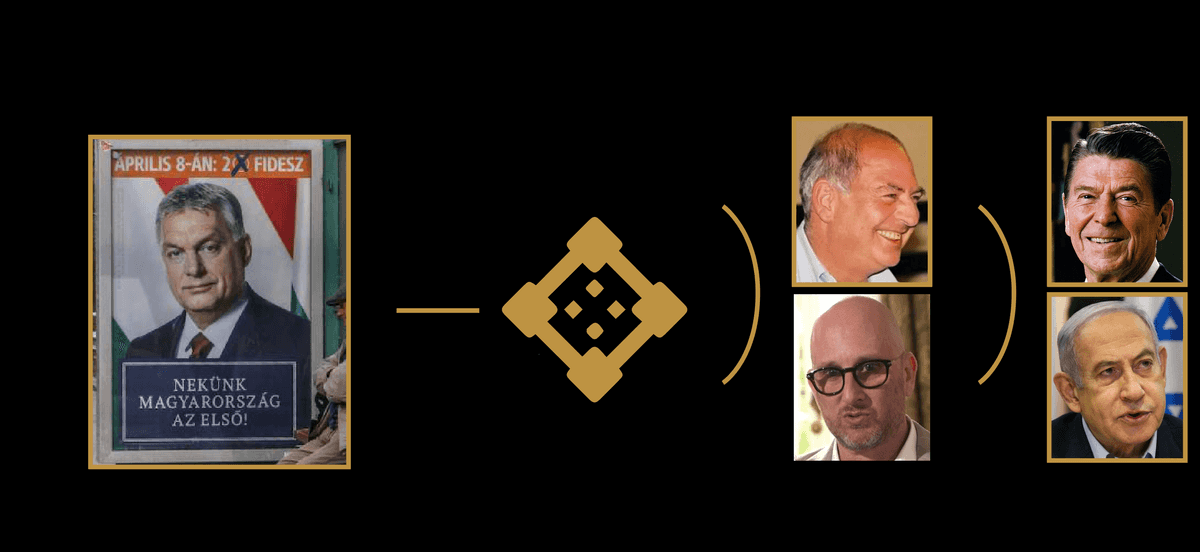

In the aftermath of the 2014 election Árpád Habony, a businessman, took a much more direct role in Fidesz’s growing media empire. His new job was to wield editorial control over Fidesz’s vast network of government-supported newspapers and media channels. These began to expand into neighbouring countries like Croatia, Slovenia, and North Macedonia,20 21 carrying out constant attacks against George Soros, an advocate for the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. These attacks were carried out on the advice of Finkelstein and Birnbaum, who had highlighted him as the new figure to be blamed for the country's problems.

However, the campaign against Soros took on a more explicit xenophobic and antisemitic tone in 2015, as many asylum seekers crossed Hungary on their way to Germany. Fidesz-aligned newspapers accused him and other “globalists” of trying to create “open borders” to destroy Hungarian culture and society.22 This conspiracy has since gone global, and although Finkelstein passed away in 2017, his reactionary legacy lives on through Habony and the Fidesz media machine, which continues to accuse Orbán’s opponents of working with Soros in each election cycle.23 24 25

Networking with the Right

In the early 2010s, large numbers of Hungarians were still actively migrating to Western Europe and to try and combat this demographic decline Fidesz began promoting the idea of a “traditional family” as a solution.26

After coming into power in 2010, Fidesz gave tax breaks to families with children to incentivize higher birth rates and provide families with more expendable income. However, despite campaigning on their generous policies in this area, by 2019 family spending as a percentage of GDP had declined to be less than it was under the MSZP government.27 Other Eastern European countries like Czechia have been far more successful at reversing demographic decline through simple cash transfers to low-income families.28 The conservative Institute for Family Studies has also admitted that Orbán has not managed to create a demographic miracle.29

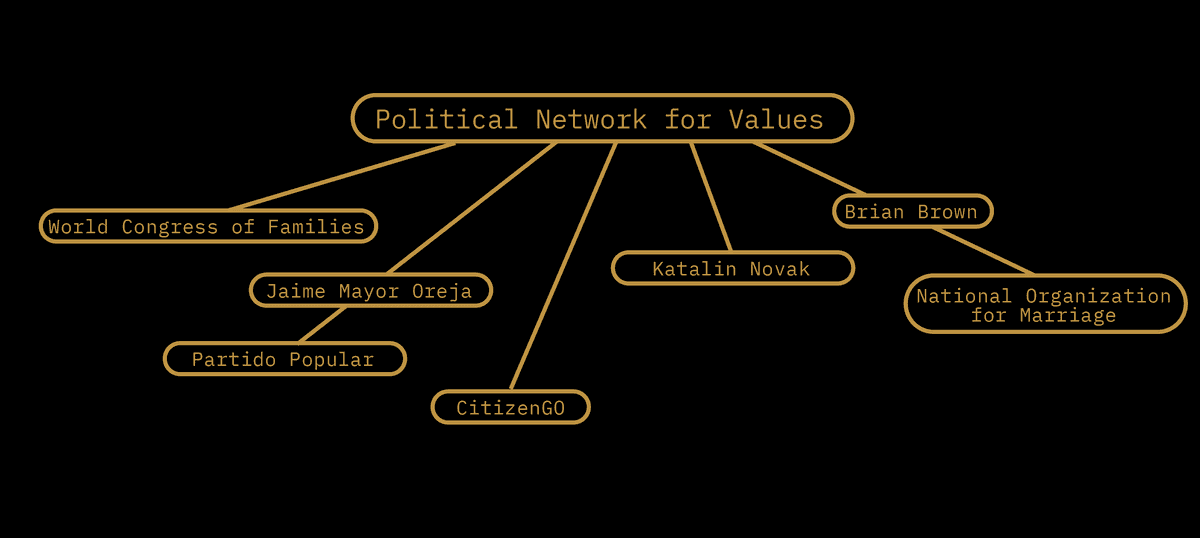

Regardless of its efficacy, Fidesz used its family policy as a form of right-wing soft power in foreign policy. We see this in the numerous conferences and events organized and attended by the policy’s chief promoter, Katalin Novak, where she forged contacts with the global Christian right. As a result, she became involved with the Political Network of Values (PNfV), an organization founded at the initiative of former Spanish Interior Minister and former MEP, Jaime Mayor Oreja of the Partido Popular.30 The organization had launched just a year earlier, but already had the backing of pre-existing hard-right anti-abortion, anti-LGBT, Christian groups. Its launch was co-sponsored by the World Congress of Families, CitizenGo, and the National Organization for Marriage, with its leader Brian Brown, speaking at the event.31 Novak quickly rose to leadership within the PNfV, eventually taking on the role of president of the group.

Novak then drew upon these connections to help organize the first biannual Budapest Demographic Summit. This gave Hungary its first real platform to promote its “family values'' policies to an international audience. The first event in 2015 was relatively small, although with notable speakers including Pope Francis and Polish President Andrzej Duda.32 The second conference in 2017 was held in conjunction with the World Congress of Families and was slated to include Trump cabinet official Ben Carson before his name was removed from the program.33 Subsequent years have featured leading political figures including Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott, and former US Vice President Mike Pence, among others. These biannual conferences did much to raise the profile of Orbán by putting him at the center of the reactionary international.34

In 2022, Novak was appointed as President of Hungary by Orbán. She was being positioned as the English-speaking friendly face of Hungary by the Orbán government until she was forced to resign in disgrace following a scandal where she pardoned a series of individuals including far-right activist, György Budaházy, and a man convicted for covering up sexual abuse at an orphanage.

Pushback

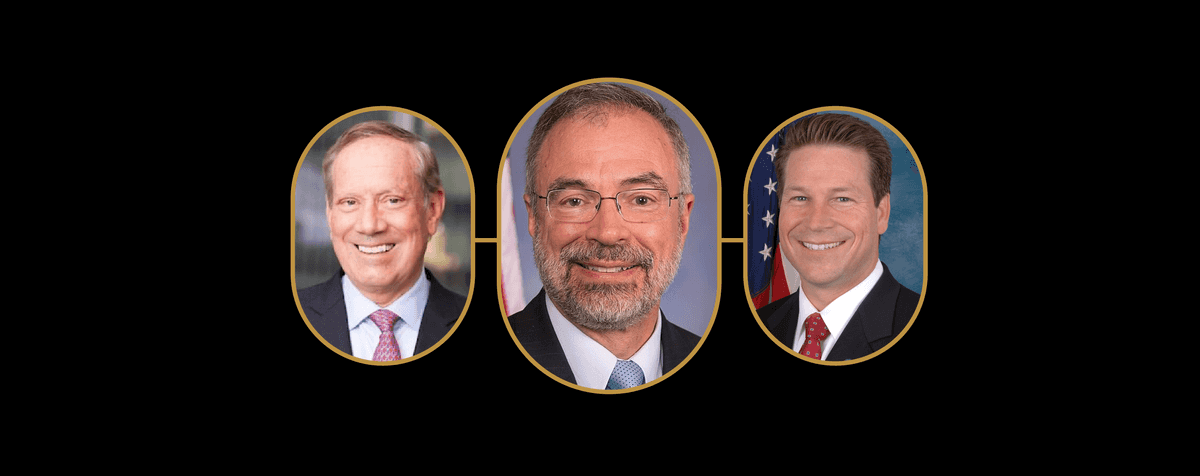

In 2018, although Fidesz once again achieved a two-thirds majority in the parliamentary elections, Orbán continued to face growing criticism for his increasingly authoritarian rule. He used his EPP allies to shield him from sanctions and called on ex-clients of Finklestein in the United States, such as former New York Governor George Pataki and former Florida Congressman Connie Mack IV, to resolve the growing diplomatic spat with the country. Connie Mack IV was paid five million dollars to lobby on behalf of the Hungarian government35 and he used his platform to defend Orbanism in the United States.36 37 Pataki, a Hungarian American, was appointed on the board of the Hungarian government-funded Hungary Foundation of North America, which sponsored various events for Hungarian Americans, including tours inspired by Israeli birthright trips.38

Yet Orbán remained an unfamiliar figure in the United States, with the closest ally in Congress being Maryland Republican Andy Harris,39 40 whose father was Hungarian. In the European Parliament, Orbán’s increasingly authoritarian policies lead to friction with their allies in the European People’s Party. It was this growing friction with the group that led the European Parliament to invoke. Article 7, which would have suspended certain EU membership rights of Hungary, however, many of Orbán's former allies in the EPP either supported or abstained from this move.

Building the Ideal Society

But despite this criticism from abroad, by 2018 Fidesz’s control over the Hungarian government was near total.

After his party’s suspension from the EPP, the Orbán government had no reason to keep up a democratic facade. While it had previously tolerated the existence of Soros-aligned institutions in the country, and within a year of the government coming to power, both the Open Society Foundation and Central European University had moved to Vienna. The new “Stop Soros” Law was passed which criminalized assisting migrants in any way,41 and Gender Studies was banned as a subject at Hungarian universities.42 The autocratic shift left him with the Law and Justice Party of Poland as his one ally in the European Union, and while the two were able to protect each other from Article 7, they were internationally isolated.

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic gave Orbán the excuse to rule by decree, and he implemented a series of laws supported by the Christian right. This included a ban on changes to one's gender assigned at birth on government documents.43 He altered the constitution once again and defined marriage as exclusively between a man and a woman, limiting the ability of nontraditional families to adopt children,44 which on top of bringing in vitro fertilization (IVF) facilities under state control,45 closed virtually all legal possibilities for LGBT+ couples to raise families. In 2021 Orbán’s government adopted a law which aimed to limit LGBT “propaganda”, similar to a law first promoted by the World Congress of Families, which has since spread across Africa. Parliament also passed a law that would allow people to anonymously report LGBT couples to the police, although it was considered so controversial it was ultimately vetoed by Novak.46

While Hungary had several formal restrictions on abortion, that dated back to the 1990s, these provisions were rarely enforced. Then in 2012, the Orbán government banned abortions through medications, requiring them to be surgical. It then slowly increased the difficulty and wait times to obtain an abortion at state-run clinics. In 2017, the government declared that it had no intention of further restricting abortion despite signing a statement saying that there was no international right to abortion.47 Yet ultimately, the government passed a fetal heartbeat bill after it was put forward by the Our Homeland Movement in 2022.48 Abortion remains legal in Hungary, but it is increasingly common for those seeking abortion to travel to another jurisdiction to terminate their pregnancies.49

Pegasus

With the country facing increasing criticism internationally, it meant that dissent could no longer be tolerated at home. This led to the Hungarian government’s purchase of Pegasus spyware that allowed for domestic surveillance and spying through hacking personal cell phones and devices.

Pegasus’ parent company, the NSO Group, requires the consent of the Israeli government to sell its software to foreign countries. However, this was not a hurdle since Orbán and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu have maintained a friendly relationship for nearly two decades.50 After a series of meetings between Orbán and Netanyahu in 2017, Hungary was authorized by the Israeli government to purchase Pegasus surveillance and hacking spyware. The first use of the Pegasus software dates to February 2018, just a few months before the parliamentary elections.

In theory, once this advanced spyware is installed on a user’s device, any data — emails, photos, text messages, files, calendars, GPS locations, etc. — are transmitted to the surveillance organization that has hacked the device. The spyware is advanced enough to bypass end-to-end encryption, activate the victim’s microphone or camera without detection or authorization, and record or extract anything of value.51 Hungarian investigative journalists at Direkt36, Index, and 24.hu, some of the few remaining independent media outlets, have been listed as potential targets of the Hungarian government’s Pegasus spying program. Lawyers, bodyguards, and former government officials and allies have all been targeted as well. In total, at least 300 Hungarian residents were targeted by the government.52 Leaked records indicate that this has led to intimidation, surveillance, and false incrimination of several of Orbán’s political and journalistic opponents, Hungarian or not.

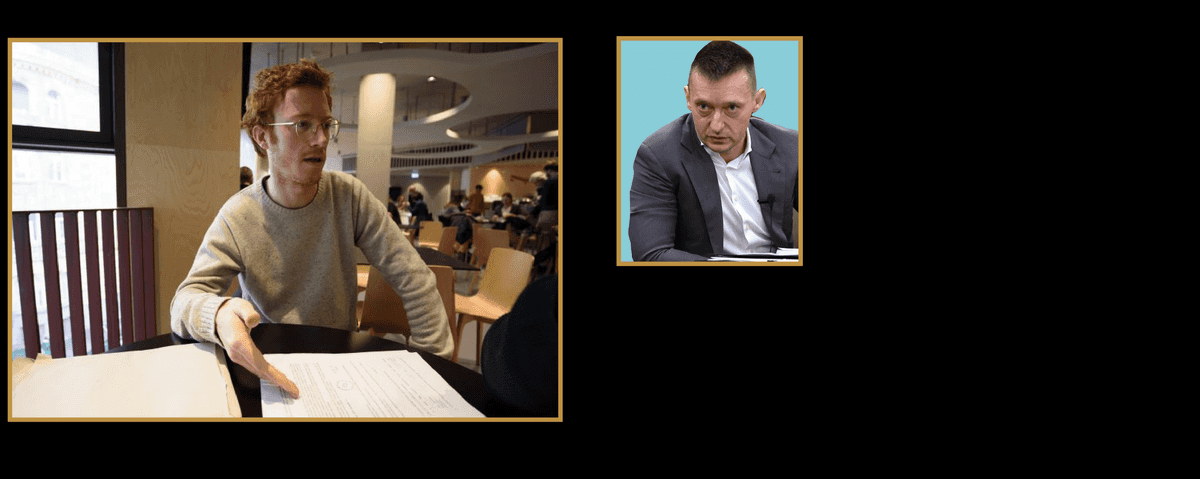

One notable, non-Hungarian victim of Hungary’s Pegasus spying program is Adrien Beauduin, a Belgian-Canadian Gender Studies PhD student enrolled at Central European University. In many ways, Beauduin is the perfect poster child of Orbán’s anti-migrant and transphobic campaigns. He was arrested in 2018 on false charges of assaulting a police officer after taking part in anti-government protests, though the charges were eventually dropped due to a lack of evidence. A forensic analysis of Beaudin’s cell phone revealed Pegasus' spying activity.53

News of the use of Pegasus spyware by Hungary against civilians leaked in 2021, but little has changed. In fact, civilian intelligence services have been brought directly under the Prime Minister’s office, under the supervision of Chief of Staff Antal Rogán.54 While a government investigation into the alleged spying was briefly launched, it was quickly archived, with one of the victims facing an investigation by the public prosecutors. A broker company involved in the sale of Pegasus to the Hungarian government even attempted to sue the organizations which reported on the hacks.

In fact, Hungary’s domestic spying has since widened in scope, with the new Tamás Lánczi lead Sovereign Protection Office launched in 2023 under the mandate to investigate any “foreign agents” in the country. Fidesz’s rise, despite being actively tied to foreign influence, has sought to weaponize claims of such influence to persecute the opposition. While the agency is justified under the frame of national security and foreign espionage, it is in fact simply used as a political weapon. Fidesz has used these claims, whether real or imagined, to impose fines on the Hungarian opposition ahead of the European elections.55 Further, it has placed former Fidesz and Hungarian opposition figure, Peter Magyar, under investigation for foreign funding.56

Yet Hungary is seemingly more than willing to turn a blind eye to foreign intelligence operations in its country as long as the country has the “right” politics. For instance, the country has overlooked the operations of Russian intelligence figures in their country and has sold EU citizenship to figures associated with the Russian government.57 For Israel, Hungary served as a middleman in a transaction that allowed Bangladesh to buy Israeli spyware. The P6 Intercept surveillance device was listed as Hungarian to get around the fact that Bangladesh does not recognize Israel and prohibits trade with it. This exchange was brokered by Haris Ahmed, who resettled in Hungary under a false name in 2015 at the peak of the country’s anti-Muslim campaign.58 Bangladeshi intelligence operatives were allowed to spy on Hungarian citizens using the technology for training and demonstration purposes59 and it is hard to imagine that this took place without the consent of the Hungarian government.

Exporting the Hungarian Model

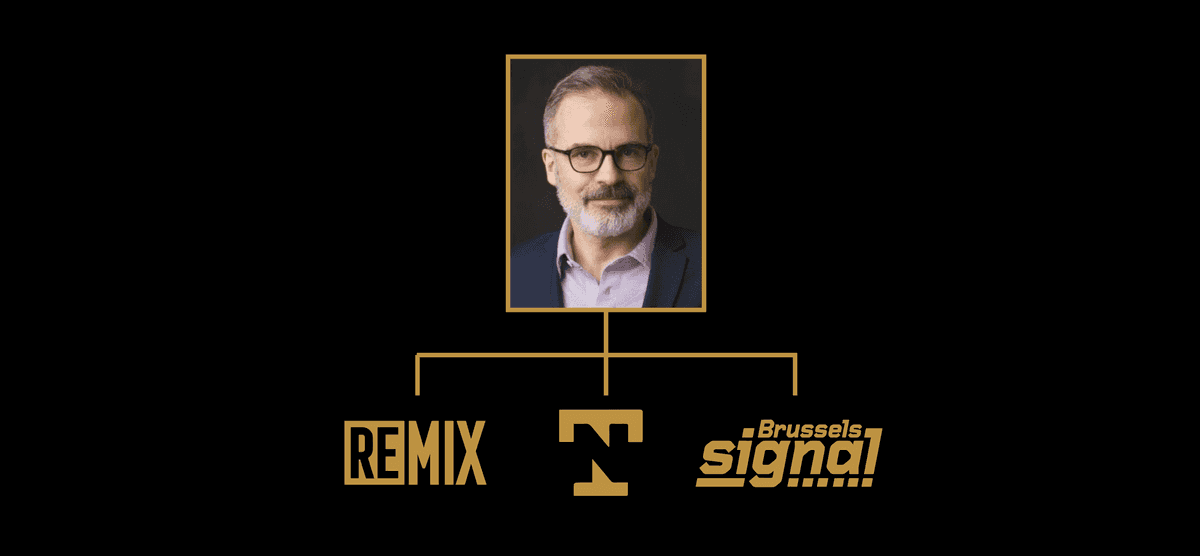

One of the first moves of the fourth Orbán government was to build an English-language media operation to communicate his vision to reactionaries abroad. They tapped Patrick Egan, a longtime consultant of Fidesz and the EPP, to head this initiative. Egan had previously been tasked by Orbán’s cabinet office to lead international communication activities in 2014.60 But his involvement in Hungarian politics goes back further: he was the programs director in both Eastern Europe and Iraq for the International Republican Institute (IRI) and was involved in several United States government-related projects in Eastern Europe dating back to 1995.61

The first project Egan launched as part of this new strategy was Remix News, a website that “offers news and commentary from Central Europe:”62 Its Twitter banner features various right-wing leaders from Europe. His consultancy, FWD Affairs, also owns the English-language Transylvania Now, which promotes Hungarian revanchism, attacking the Romanian government and praising Orbán.63 More recently, Egan has launched the Brussels Signal,64 one of several new English-language initiatives involving Fidesz in Brussels in recent years. Other such initiatives have included the relaunch of the European Conservative, now owned by the Orbán government,65 and the launch of a Brussels-based research arm of the Mathias Corvinus Collegium.66

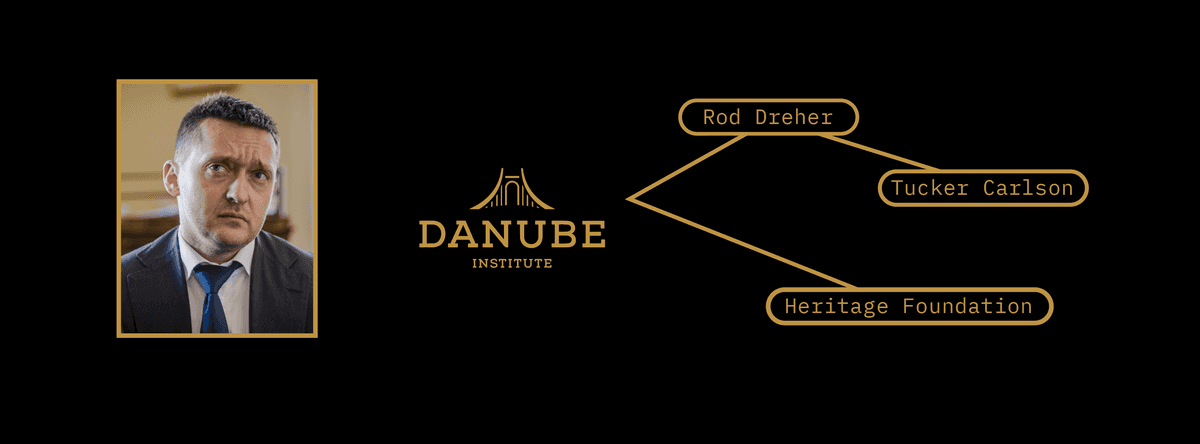

Antal Rogán, Orbán’s chief of staff and a key node in Fidesz’s network of allied newspapers has directed billions in state funding towards the Danube Institute since 2018. Notably, the Danube Institute contracted the conservative American author, Rod Dreher, who was paid $105,000 a year by the Hungarian government (about six times the average Hungarian salary).67 Dreher played a key role in Tucker Carlson's tour of Hungary in 2021, where he interviewed Viktor Orbán on prime-time television and broadcast his views to millions in the US.68

The Danube Institute has also been able to secure a partnership with the US arch-conservative tank, the Heritage Foundation. Danube and Heritage have since hosted a conference together and signed an agreement that will send four Heritage researchers to Hungary every year.69

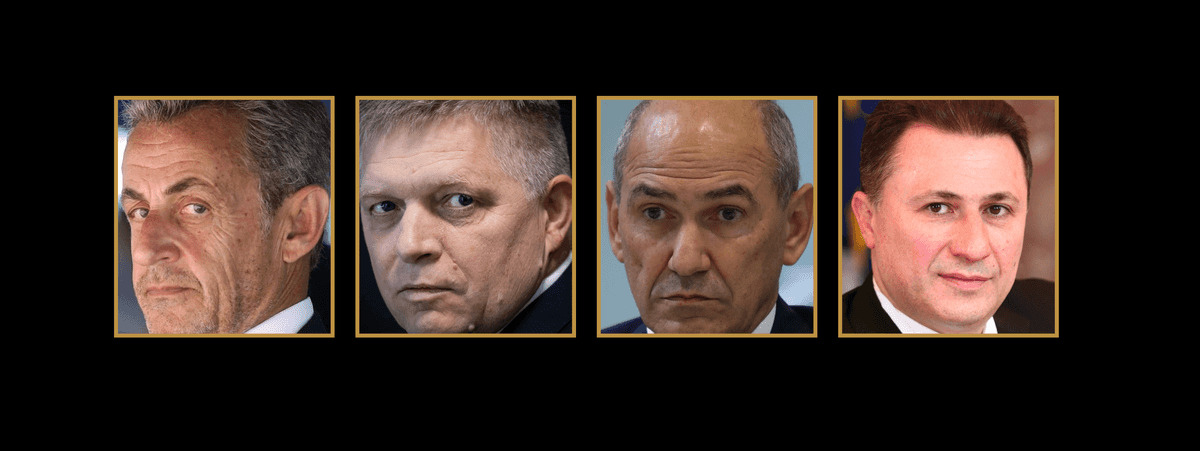

Meanwhile, Árpád Habony has become increasingly influential in the government in recent years.70 71 The Hungarian government has spent millions of dollars on advertisements throughout Europe in an attempt to influence numerous elections.72 Habony played a key role in these influence operations of the Orbán regime, having also worked as a political advisor for conservative figures in numerous countries. These include Sarkozy in France;73 the former ruling government of Poland, Law and Justice; the Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico; former Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Janša; and the former North Macedonian Prime minister74 who was later forced to flee his own country and seek political asylum in Hungary. Reportedly Habony is also in talks to work for Donald Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign.75 76

Courting the American right

One of the biggest focuses of Hungarian foreign policy in recent years has been strengthening its alliance with the US right. Donald Trump’s defeat in the 2020 presidential elections, presented a leadership vacuum on the international right-wing that allowed Orbán to gain influence. Hungarian President Katalin Novak met with both Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and Trump ahead of the 2024 Republican primaries and conferred with Elon Musk, speaking also about Hungary’s policies to combat demographic decline.

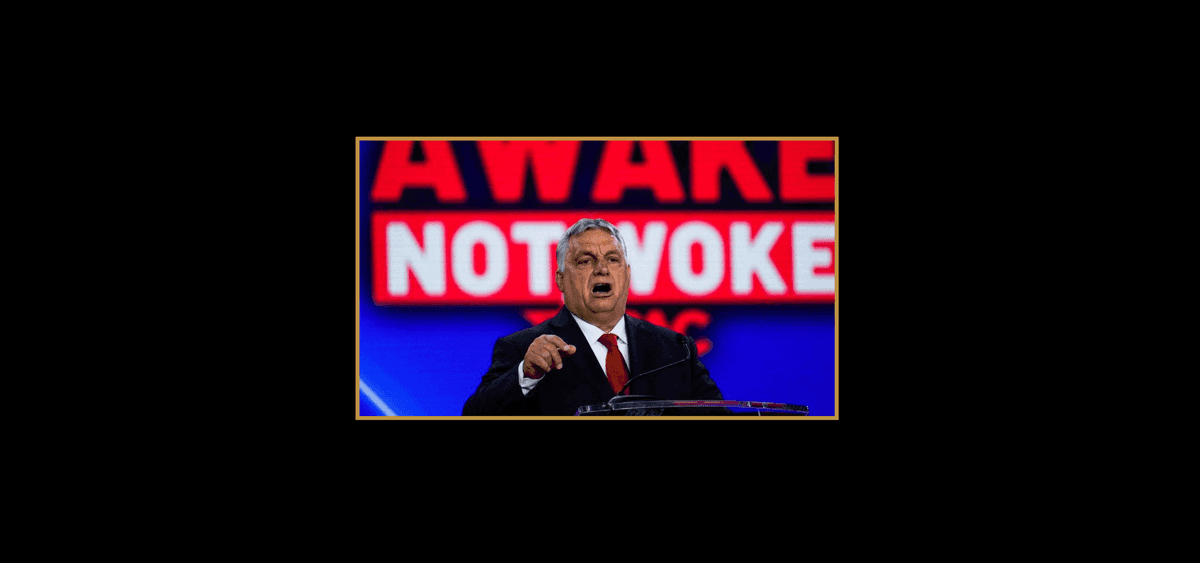

Orbán has been rewarded for his efforts by winning the bid to host the European edition of the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Hungary, an influential event for the US right-wing. At CPAC Hungary in May 2023, Viktor Orbán boasted that Hungary is “an incubator, where experiments are being conducted for the conservative politics of the future. Hungary is the place where we not only talked about defeating progressive liberals and turning in a conservative Christian political direction, but the place where we have actually done it.”77 Additionally, István Kiss, the Executive Director of the Danube Institute argued at CPAC Texas that Hungary’s child protection legislation directly inspired Florida’s banning of “gender ideology” in schools.

On April 25, 2024, CPAC Hungary hosted its third edition, in which Orbán made every attempt to appeal to the US right-wing. During a recent visit to the United States, which took place during the State of the Union, Orbán avoided meeting with any Biden administration officials. Instead, he met with Trump and spoke at the Heritage Foundation about his country’s family and economic policies.78 Orbán also met with neofascist Steve Bannon at the Hungarian Embassy in Washington DC.79

Orbán’s divisive policies and far-right rhetoric hope to translate his connections with the Reactionary International into victories in 2024, allowing him to consolidate his regime at home. As Orbán said in his 2022 speech at CPAC: “The globalists can all go to Hell.”