On the occasion of its youth wing’s annual party ‘Fenix 2025’, Fratelli d’Italia’s leader and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni paid homage to far-right political activist Charlie Kirk: “Charlie Kirk was frightening because he was good at demonstrating how unreasonable some of the arguments that they want to force on us really are. He was dangerous because he dismantled the narrative imposed by the mainstream with logic, because he gave a voice to the majority of people who think exactly like him and who ended up feeling wrong.”1

Charlie Kirk, who was killed during a political rally in Utah on 10 September, had grown famous for his promotion of far-right ideology to young audiences across the United States — from the great replacement theory to a new male chauvinism to a call for civilisational struggle on behalf of the West against the rest.2

Meloni’s tribute at Fenix 2025 was more than a celebration of Kirk’s legacy. Rather, it articulated the growing ties between the reactionary right in the United States and the homegrown ‘post-fascism’ that governs Italy’s ruling party.

To understand those ties — and the deeper ideological currents that run between them — it is necessary to trace how ideas that were once confined to the margins of Italian politics have endured, adapted, and resurfaced within the democratic framework of the Italian Republic — and what their resilience means for the fate of the Reactionary International on the European continent.

Anatomy of a Shadow State: Fascism, Terror, and the Strategy of Tension

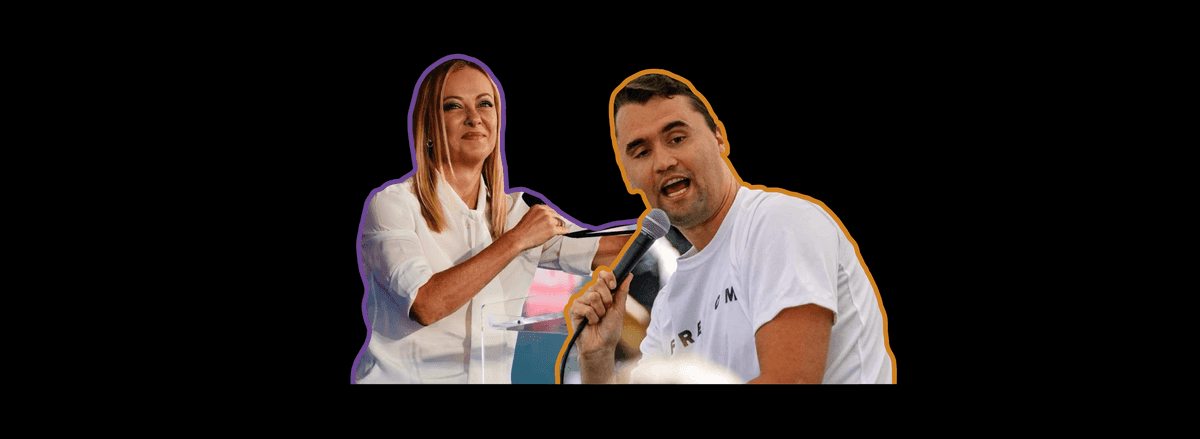

The Fascist movement was born out of a context of deep social and economic crisis. As Robert O. Paxton argues in The Anatomy of Fascism, its emergence must be understood not only through the intellectual and cultural influences on Benito Mussolini, but also through the anxieties and fears to which fascism offered a remedy. After the First World War, Italy was pervaded by a sense of national decline and humiliation. In the turmoil of the Biennio Rosso (1919–1920), when widespread strikes and worker occupations shook the foundations of liberal capitalism, fascism took root as a counter-revolutionary response. Supported by conservative elites and landowners who viewed Mussolini’s movement as a tool to restore order and protect property, the squadrismo violence of the early 1920s eroded liberal democracy from within. By 1922, fascism’s ascent was not the result of popular mobilisation but of elite collaboration and royal acquiescence, what Paxton describes as a series of anti-socialist compromises that paved Mussolini’s road to power.

After the defeat of the Fascist regime by the Italian resistance and the Allies, Mussolini continued to lead the Italian territories controlled by Nazi Germany until April 1945. It was in these territories, known as La Repubblica Sociale Italiana or Repubblica di Salò, that Giorgio Almirante became the Head of Cabinet of the Ministry of Culture. Previously, he had been a journalist for La Difesa della Razza (The Defence of the Race), a periodical born in 1938 that, it goes without saying, was aligned with the anti-Semitic and racist turning point of the fascist regime. Arturo Michelini and Licio Gelli, who had also participated in respectively more and less important positions in the National Fascist Party, both adhered to the Repubblica di Salò, where Gelli himself became liaison officer between the Fascist puppet state and Nazi Germany.

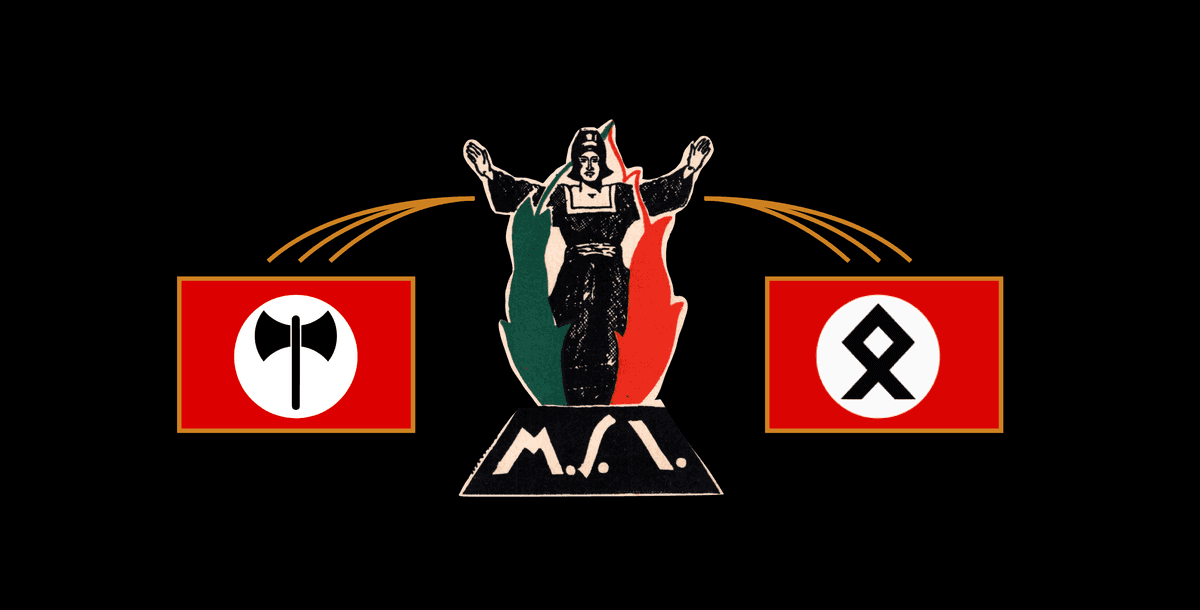

These three people became quite important in post-war Italy. Michelini and Almirante were amongst the founders of Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI) in 1946, which was created to keep alive the idea of fascism and its legacy in the new Republican Italy. Licio Gelli, who also participated in the MSI, as we will see later, became the Venerable Master of the clandestine right-wing Masonic lodge Propaganda Due (P2).

The Years of Lead (1969-1982) were a period of heightened political violence that spread throughout the country. While the terrorist group Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades) is possibly the most infamous organisation of those years because of its high-level targets, there were also many neo-fascist terrorist groups which engaged in indiscriminate bombings, most notably Ordine Nuovo, Avanguardia Nazionale, Ordine Nero, and Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari.

It was the Piazza Fontana bombing by Ordine Nuovo that marked the beginning of the Years of Lead and the exemplification of right-wing stragismo. Stragismo refers to the series of bombings that began in the late 1960s and caused significant casualties over several years. Early investigations blamed anarchist and far-left groups, following what was termed the “red trail.” However, later inquiries revealed evidence of a “black trail,” indicating that far-right groups were responsible and had deliberately tried to shift suspicion onto the left. These findings exposed the so-called Strategy of Tension, a plan designed to spread fear and instability to steer Italy towards authoritarian rule.3 Central to this strategy was portraying the main threat as left-wing subversion, particularly in response to centre-left governments formed from 1963, the growing unrest among students and workers in 1968–1969, the growth of the Italian Communist Party into the largest in Western Europe, and the progressive policies that characterised the 70s (e.g. Italian law on divorce in 1970).

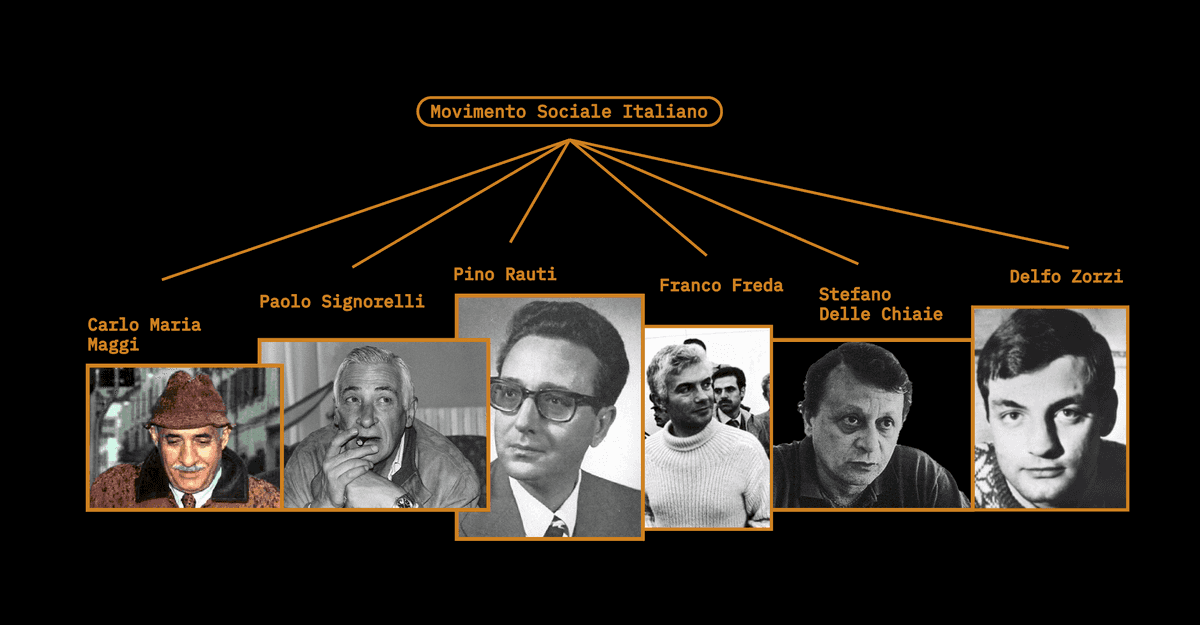

What is interesting here is that the MSI was the birthplace of several neo-fascist terrorist organisations that were responsible for numerous bombings during that period, like Ordine Nuovo and Avanguardia Nazionale. Key figures moved between these organisations, maintaining both political and operational continuity. Pino Rauti, a founder of MSI, left the party in 1953 to create Ordine Nuovo and later returned to Parliament. Carlo Maria Maggi and Paolo Signorelli followed him back into MSI, taking leadership roles while being implicated in violent acts, including the Brescia bombing. Stefano Delle Chiaie, Franco Freda, and Delfo Zorzi similarly emerged from the party to take part in neo-fascist terrorist groups. Delle Chiaie founded Avanguardia Nazionale after joining Ordine Nuovo 4. Numerous members who were accused or convicted of taking part in the armed struggle of the far-right had rejoined the Movimento Sociale Italiano in 1969.

But the Strategy of Tension did not only include bombings and overt displays of political violence, and the actors were not limited to terrorist groups. Judicial findings and parliamentary investigations have pointed out links connecting the actual perpetrators of violence with subversive sectors of the Italian state apparatus, most notably the Italian Secret Services (SID), Carabinieri (Italian gendarmerie) and Licio Gelli’s P2, but also international stay-behind operations such as Gladio.5

These relations consisted of repeated obstruction by cover-ups and false leads (depistaggi) by the state’s subversive sectors and protection of violent groups and the masonic lodge P2, of which many officials who obstructed investigations belonged. Not only that, but members of P2 had also been behind Golpe Borghese, an attempted coup d’état in 1970. The parliamentary commission refers to these relations as a triangulation between subversive secret services, P2 and stragismo, which characterised the strategy of tension during the Years of Lead.6 It is worth noting that although most piduisti were Italians operating in Italy, the organisation also included Argentinian golpista Emilio Eduardo Massera and José López Rega, Argentinian Minister of Social Welfare during the military dictatorship and founder of the paramilitary organisation Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (AAA). The organisation also had strong ties in Uruguay.

The Heirs: From Post-Fascism to the Premiership

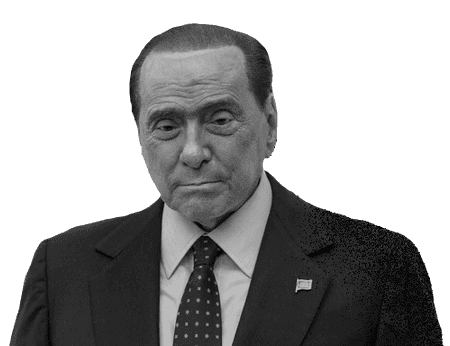

Another important piduista that would drastically impact the political history of Italy is Silvio Berlusconi, the uncontested winner of the crisis that characterized Italian politics in the early 1990s. The crisis, started in 1992, was the result of a series of judicial investigations that uncovered systemic corruption between political parties and Italian enterprises and eventually led to the dissolution of most of the post-war parties.

During that period, the MSI, which had been kept outside the mainstream parties until then, seized the opportunity to change its image. Under Gianfranco Fini, MSI embraced a post-fascist image to create a new Italian right that sought consensus on the wider conservative spectrum, shedding the remnants of its blatantly violent past to be palatable to a wider audience. It was the right time to gain consensus and legitimacy. After changing its name from MSI to Alleanza Nazionale, the party found itself in the winning centre-right coalition led by Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, who effectively, in his words, ‘legitimised and constitutionalised the Fascists’.7

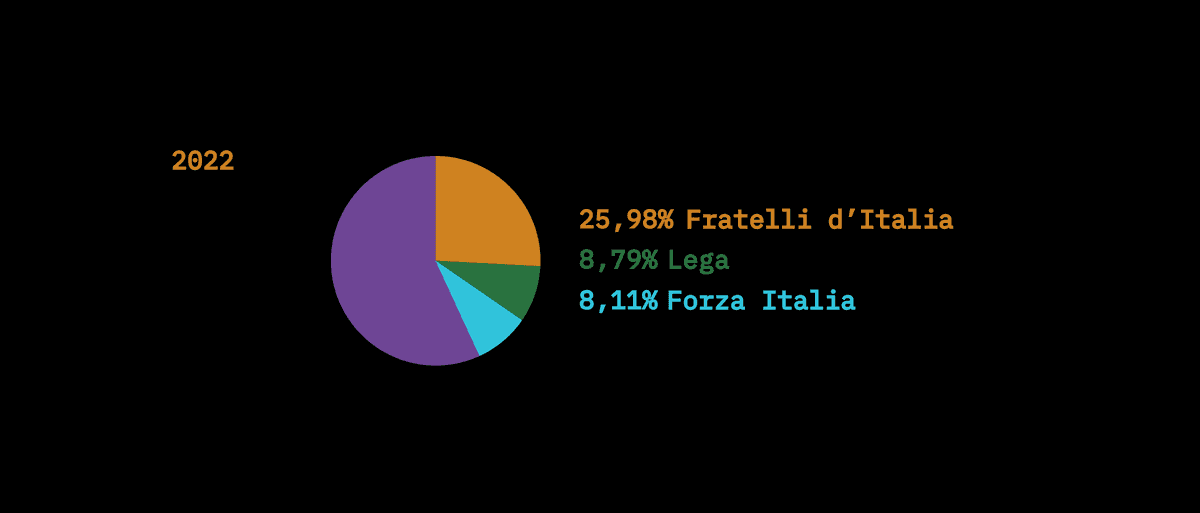

The formation of Alleanza Nazionale contributed to the mainstreaming of the far right, but it never reconciled the tensions within the movement. Fini’s attempt to distance Italian conservatism from its fascist roots was only partially successful and rested on fragile ground. This unstable path eventually opened the way for Giorgia Meloni, who started her political career in the MSI before moving into Alleanza Nazionale, and later founded her own party, Fratelli d’Italia, with Guido Crosetto and Ignazio la Russa in 2013. Riding on the legitimacy that Alleanza Nazionale had gained, Fratelli d’Italia grew from 2 to almost 26% in 9 years, securing the elections in 2022 as the leading party of a right-wing coalition with Forza Italia and Lega.

Lega also deserves a brief examination. Founded in 1991 by Umberto Bossi as Lega Nord (Northern League), the party emerged from the merger of six regional parties from northern Italy. Being a right-wing federalist movement, it campaigned for greater regional autonomy from Rome and sought to distance the wealthier north from Italy’s poorer southern regions. The party kept its explicitly regional label until 2018, when it rebranded as Lega and adopted a more national strategy. While its early rhetoric was marked by fierce anti-southern sentiment (epitomised by Matteo Salvini’s derisive attacks on Neapolitans, from calling on Vesuvius to engulf them in fire, to mocking them for poor hygiene, to opposing the migration of southerners seeking work in the north), the party later redirected its hostility towards migrants. In this shift, the “new southerners” became those arriving from outside Europe, with immigration replacing the south as the principal “other” in Lega’s political discourse.

As stated earlier, the 2022 elections, which had the lowest turnout in the history of the Italian Republic, resulted in a right and far-right governing coalition with Fratelli d’Italia at almost 25,98%, Lega at 8,79% and Forza Italia at 8,11%.

The Illiberal Turn: Democratic Erosion Under Meloni's Coalition

Since the 2022 elections, Giorgia Meloni has governed in coalition with Lega and Forza Italia. While her foreign policy has largely shielded her from criticism at the European level, the domestic policies, legislative initiatives, and rhetoric of the coalition have raised concerns about democratic backsliding in Italy.

For instance, the government has increasingly relied on decrees to bypass parliamentary scrutiny, weakening democratic oversight. Other policies and laws reinforce concerns about an illiberal turn:

- The Security Law (April 2025): adopted through an emergency decree, it restricts the right to peaceful assembly and protest. The OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights and the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights warned that its vague wording could enable arbitrary prosecutions and disproportionately target migrants, racial minorities, and prisoners.8

- Government officials have been repeatedly using defamation laws to sue intellectuals, academics, and journalists to silence them.

- The Justice Reform: in discussion, can potentially undermine judicial independence from political control.

- Premierato reform: the proposal enhances the powers of the prime minister, concentrating them in the hands of the executive.

Journalists at the public broadcaster RAI have repeatedly denounced government interference and censorship, with several strikes organised in response to what they describe as “suffocating control”. A prominent example was the cancellation of Antonio Scurati’s monologue for Liberation Day on 25 April 2024, an episode widely criticised as an attempt to silence dissent on fascism.9

Nurturing the Roots: The Unbroken Chain from MSI to Fratelli d'Italia

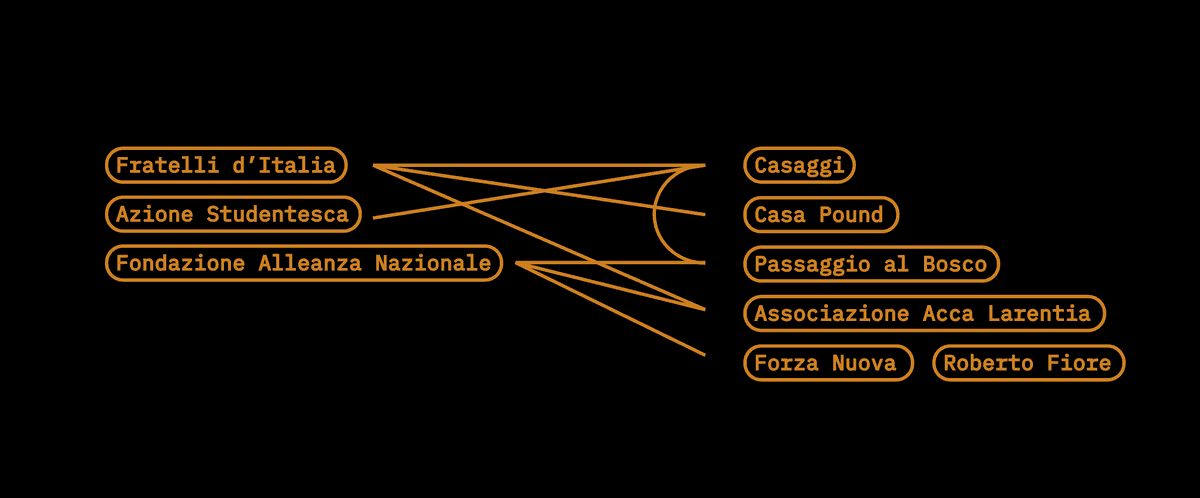

Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) maintains an extensive domestic network that links it to organisations which, remaining outside the public spotlight, enjoy greater freedom to express overtly fascist views. The keyhole through which one can peek into the complex Italian far-right universe is Gioventù Nazionale, the party’s youth wing.

This organisation has been at the centre of a journalistic investigation that revealed troubling insights into the environment where many FDI politicians are politically and ideologically formed. An investigation by Fanpage documented fascist salutes, chants of Sieg Heil, and what members themselves described as a “strategy of self-censorship” when interacting with journalists10. Once the cameras were off, however, the footage exposed gatherings modelled on the MSI’s so-called “Hobbit camps”, which Giorgia Meloni herself attended in the past11, where members spoke openly about their beliefs. MSI Hobbit Camp teenagers, sitting in a Celtic cross.

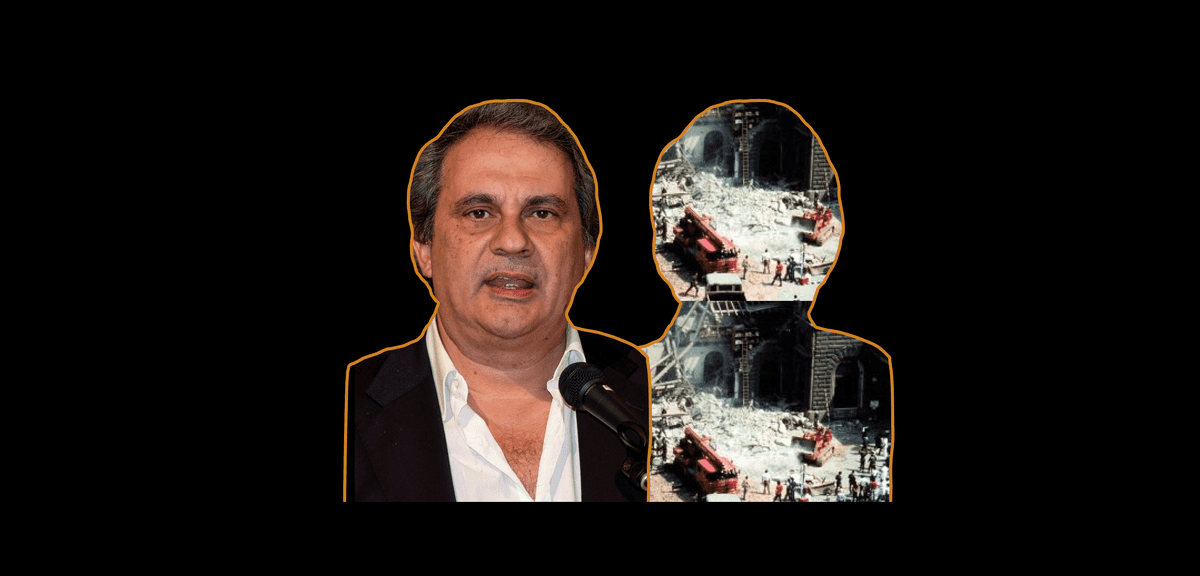

During these and other occasions, participants were shown carrying out propaganda actions, such as putting up stickers across Rome bearing slogans like “Reject modernity, embrace fascism,” and openly identifying as fascists and racists. One member even boasted of her father’s personal connection with the neo-fascist terrorists responsible for the 1980 Bologna Station bombing. Although Giorgia Meloni publicly distanced herself from these episodes, the investigation also captured prominent FdI figures such as Nicola Procaccini performing gladiatorial salutes alongside militants.

The investigation further revealed links extending beyond Gioventù Nazionale. In one of the organisation’s local headquarters regularly visited by Arianna Meloni (the party secretary and Giorgia Meloni’s sister) and FdI parliamentarians, the undercover reporter found publications by individuals associated with far-right groups such as Casaggì and CasaPound. On social media, connections between the student branch of Gioventù Nazionale, Azione Studentesca, and centres like Casaggì are easy to trace. Their online biographies are intertwined, mentioning each other and providing a glimpse into the dense and overlapping ecosystem of Italy’s far-right scene.

Casaggì, for example, is closely tied to the publishing house Passaggio al Bosco, which counts around two hundred authors and specialises in works glorifying fascist values, publishing Mussolini’s and Sir Oswald Mosley’s speeches, and promoting an “identitarian” vision of Italy and Europe. The website gives a clear overview of the work published, ranging from white guilt to remigration theories and identitarianism.

Passaggio al Bosco is also linked to the Fondazione Alleanza Nazionale, the financial arm of Fratelli d’Italia, of which Arianna Meloni is a member. The foundation has organised events promoting the publisher’s works, such as the book Siena s’è destra. Moreover, it has been associated with the Associazione Acca Larentia, to which it donated €30,00012, and with far-right and no-vax groups, including Roberto Fiore’s Forza Nuova, which received funding in 2021, when FdI was still in opposition but several of its members, including Ignazio La Russa, sat on the foundation’s board13.

Roberto Fiore, convicted for the assault on Italy’s largest trade union, CGIL, during the no-vax protests in 2021 and now living abroad, has been president of the Alliance for Peace and Freedom since 2015. Fiore was also connected to the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari, responsible for the 1980 Bologna bombing. The Alliance for Peace and Freedom functions as a pan-European platform linking Forza Nuova with a range of fascist and neo-Nazi parties and movements across the continent.

A Spiritual Association: Meloni, Orbán, and the Remaking of the European Right

Looking at its domestic network and the flow of ideas that rise from smaller groups towards the party leadership, it becomes clear that the political heir of fascism in Italy now presents itself as a defender of Europe and the West rather than merely the Italian nation. This repositioning is also reflected in Giorgia Meloni’s international ties.

Meloni has been one of Donald Trump’s staunchest allies and supporters in Europe. Her role as Europe’s “Trump whisperer” seems to have taken precedence over her relationship with Elon Musk. Following the fallout between Trump and Musk, Musk’s presence in Italy has notably weakened, despite alleged negotiations in January 2025 over a €1.5 million deal between the Italian government and Starlink. Musk’s personal contact in Italy, Andrea Stroppa (often referred to as “Musk’s man in Italy), offers insight into the shifting dynamics between the government and Musk, a relationship that appears to mirror his oscillating alliance with Trump. After a period of distance following their dispute, things may change again as Musk and Trump appear to be reconciling. Meloni remains close to Trump, who even wrote the foreword to her most recent book.

Another evolving relationship is that between Steve Bannon and Italian politicians. After Matteo Salvini joined Bannon’s Movement back in 2018 and maintained close ties with Meloni for a time, it is now unclear where that relationship stands. The defence of so-called Western values also underpins Meloni’s friendship with Viktor Orbán. Orbán, who is also close to Salvini and awarded him the Medal of Honour for the Protection of European Values and Freedom in March 2020, has described Meloni as a “spiritual sister”.14

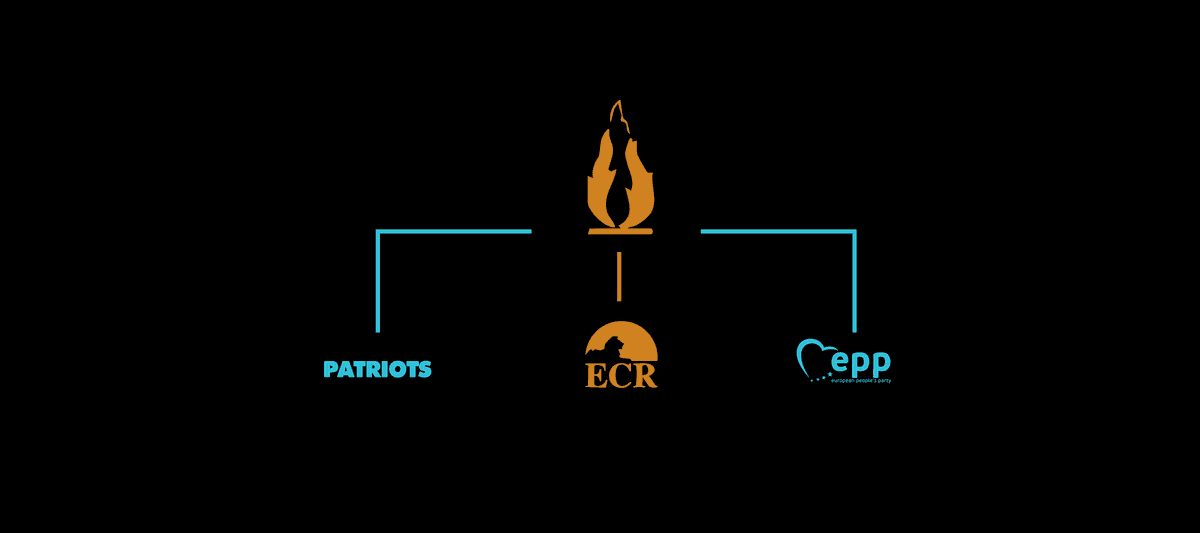

At the European level, Fratelli d’Italia is part of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) parliamentary group but maintains strong links with both the European People’s Party (through Forza Italia) and the Patriots group (through Lega and close-ally Vox). This positioning places Giorgia Meloni in a uniquely advantageous role, allowing her to bridge the centre-right and far-right blocs in the EU parliament.

Overall, Meloni has capitalised on the legitimacy that figures like Fini and Berlusconi once secured for the Italian right, using it to normalise increasingly hard-line positions. While many EU observers were initially reassured by her moderate foreign policy stance and pro-Atlantic alignment, these gestures concealed a consistent ideological continuity. Her rhetoric, alliances, and domestic agenda have all revealed the true contours of her politics. Her strategy differs from that of her ally, Orban. Instead of open confrontation with Brussels, she has pursued a quieter consolidation of power, seeking to rally the three right-wing groups within the European Parliament to marginalise the left and shift the EU’s ideological centre of gravity further right.15

By quietly rallying Europe’s right-wing groups and isolating the left, Meloni is reshaping both Italian and European conservatism from within. Beneath the language of tradition, identity, and sovereignty runs an unbroken current of authoritarian thought, as shown from FdI’s domestic network. Its forms have changed; its roots have not. As the old MSI nostalgics and neo-fascists often recall, quoting J. R. R. Tolkien: “Deep roots are not reached by the frost.” The endurance of this political culture shows how Italy’s fascist legacy continues to nourish the politics of the present, making it a relevant contribution to the reactionary international.