The Coup in Brasilia

On January 8, 2023, Brazil’s democracy — the largest in Latin America — faced immense turmoil when riots erupted over former President Jair Bolsonaro’s electoral defeat to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in October 2022. His most ardent supporters, or “Bolsonaristas,” stormed the National Congress of Brazil, the Federal Supreme Court of Brazil, and the Planalto Palace in Brasília to restore the far-right leader to power. The attempted coup was orchestrated by some 4,000 people; who trashed the Supreme Court with broken bottles and glass, set off fire hydrants, tagged “Supreme are the people” on a historic wooden table, and stole a replica of the 1988 constitution, all while donning the country’s yellow and green flag colors.

Washington’s Influence

Taking place almost exactly two years after the January 6 Capitol riots in Washington, many media outlets shared concerns that the Brasilia insurrection was a copycat case, evidence of Brazil’s imported Trumpism. The BBC reported that “Bolsonaro supporters railed online about an existential crisis and a supposed "communist takeover" — exactly the same type of rhetoric that drove the rioters in Washington two years ago.”1

The riots were unique in a few ways: namely because elected officials were not present at the site, and the event had been widely predicted. Following his defeat on October 30th, Bolsonaro silently fled to Florida and filed for a 6-month U.S. visitor visa, refusing to give away his presidential sash. For 10 weeks, the protestors camped in front of the Army Headquarters just kilometres away from the capital’s government buildings, calling for military intervention to reinstate Bolsonaro. And a week after Lula was sworn in on January 1, 2023, they rioted.

Support from conservative US pundits and authorities was key in the lead-up to the insurrection — and revealed part of the Reactionary International’s network. In October 2022, Jair’s son and congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, who was almost appointed as Brazil’s ambassador to the US in 2018, visited Donald Trump at his resort in Mar-a-Lago, Florida, and had calls with Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist.2 Eduardo, a professed fan of Trump and Bannon, was named South American representative for The Movement in 2019, a coalition of far-right nationalist leaders founded by Bannon. In 2022, Agência Pública recorded 77 visits between prominent MAGA supporters and Eduardo.3

When Lula won the election in 2022, Bannon took to Gettr, the conservative social media app, casting doubt on the voter count.4 After the insurrection, he called the protestors “Brazilian Freedom Fighters.”

The Military Coup (1964)

Background

2023 wasn’t the first time a coup d’état in Brazil was leveraged by the US. On the night of 31 March, 1964, President João “Jango” Goulart, a social democrat and member of the Brazil Labour Party, was ousted by a coup led by the Brazilian Armed Forces with significant backing from the US government, launching a 21-year-long dictatorship. In 1963, under pressure from labor unions and radicals, Goulart began enacting socially-minded policies such as agrarian reforms, against the will of conservative Brazilian elites, armed forces and the US government.

Little by little, a campaign against Goulart and Operation Brother Sam—code for the US delivery of clandestine weapons to the Brazilian Armed Forces—started forming through the early 60s, as the US feared a leftist takeover of Brazil. Agency for International Development and Central Intelligence Agency officers started entering Brazil. The US embassy also financed Goulart’s opposition in the 1962 municipal election.5 By 1964, they successfully stoked fears of a non-existent communist threat in Brazil.

“My considered conclusion is that Goulart is now definitely engaged on a campaign to seize dictatorial power, accepting the active collaboration of the Brazilian Communist Party, and of other radical left revolutionaries to this end,” said Lincoln Gordon, US Ambassador to Brazil, in a state address on March 28, 1964.6 A few days later, the Armed Forces successfully took over.

Over the days following the coup, Goulart was deposed and fled to Uruguay; members of the National Congress handed the state to General Castello Branco and instated a military junta.

Student movements and resistance under the military dictatorship

As hardline military generals restricted the civil rights of Brazilians, and abolished all political groups but the National Renewal Alliance and Brazilian Democratic Movement party, mass groups of workers, students, leftist militants and Indigenous people fought back. Throughout the 60s, students in Brazil were inspired by the Cuban Revolution. During a protest in March 1968, police forces killed a high school student, Edson Luís de Lima Souto—later in June, 100,000 people attended a march in Rio de Janeiro protesting police violence and the dictatorship.

Dissidents were tracked, imprisoned or disappeared. The Department of Internal Operations (DOI-CODI) torture tactics and doctrine were inspired by the US School of the Americas, and their intense psychological interrogation method by the ‘English System.’7 Indigenous people were especially persecuted during this time; in the 60s, CIA agent Daniel A. Mitrione was sent to train Brazil’s military police in Minas Gerais and inspired them to create the Indigenous Guard.8

The Bolsonaro family’s military apologia

Jair Bolsonaro, a former military captain during the 64-85 dictatorship, has often expressed nostalgia for the dictatorship, during which 434 people were killed or forcibly disappeared, and 20,000 tortured, according to Brazil’s National Truth Commission.9

In support of PT’s (Worker Party's) Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment in 2016, Bolsonaro said: “They lost in ‘64, they lost now in 2016 … against Communism, for our freedom … in memory of Colonel Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, the terror of Dilma Rousseff … for our Armed Forces, I vote yea.”

On 31 March 2019, on the fifty-fifth anniversary of the coup, a video was released by the presidential palace, praising the Armed Forces. Eduardo Bolsonaro reacted to the video, saying “On a day such as this one Brazil was liberated. Thank you armed forces of 64! Ask your parents or grandparents who lived in that period how it was!”10 A year later, President Bolsonaro called the anniversary “freedom day.”11

A Nation Divided

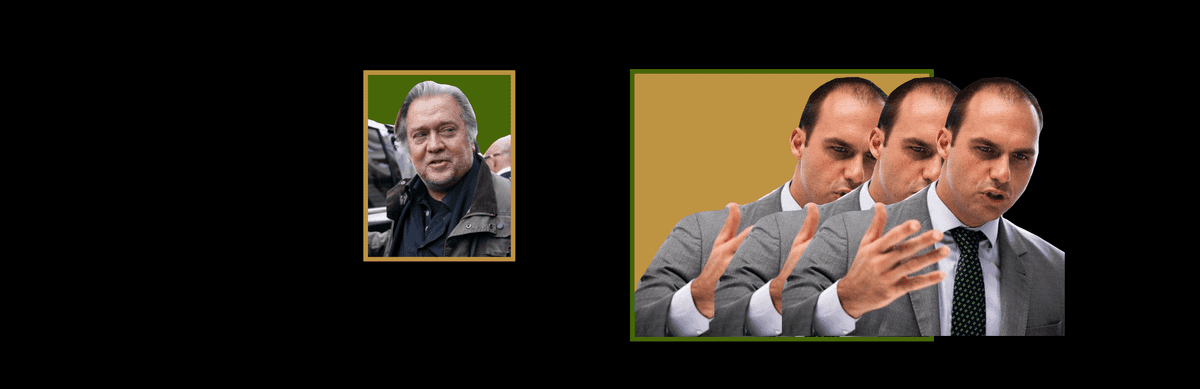

By 1980, Brazil had the highest level of debt in Latin America. As anti-dictatorship sentiment spread, the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT or Worker’s Party) was born. Lula da Silva, a long-time union leader born in northeastern Brazil, became an unlikely star for the party — a group of intellectuals, Catholic liberation theologists, trade unionists and students — heralding a new era of left-wing politics for the country amidst an increasingly hostile and reactionary environment.

As Brazil transitioned from a dictatorship to a democracy in 1985, Lula was elected to Congress under PT. In October 2002, he claimed victory as president and served two terms; becoming Brazil’s most popular president in recent memory, with an 80 percent approval rate.12 His welfare programme lifted millions out of poverty and helped tackle Brazil’s pressing food insecurity. In 2010, he hand-picked former guerilla member, Dilma Rousseff, as his successor.

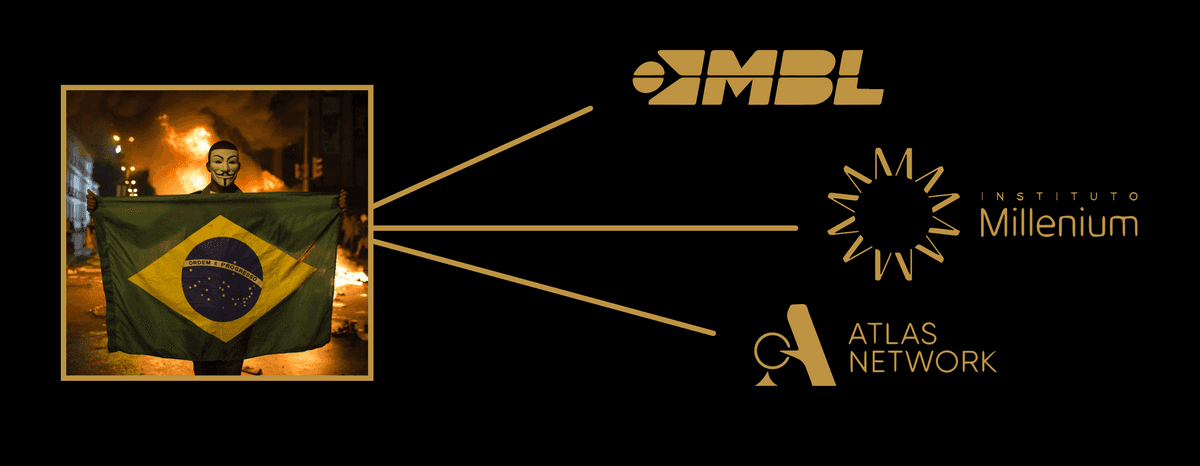

However, antipetismo, or anti-PT-ism, was spreading throughout Brazil. A few years later in June 2013, nationwide protests erupted over political corruption, public transport fares and demands for better public services. These were later co-opted by Brazilian nationalists to bring down PT’s Dilma Rousseff — and facilitated by right-wing Facebook groups like O Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL), WhatsApp, the Millenium Institute and the Koch family-funded Atlas Network.13 14

The Legal Coup (Lava Jato)

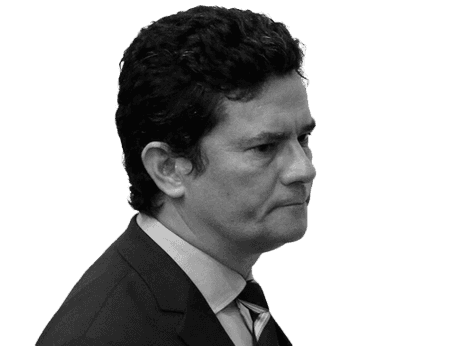

By 2014, the Lava Jato (Car Wash) investigation began, dubbed the largest anti-corruption scandal in Brazil’s history. What started as a probe into a gas station’s money laundering snowballed into a multi-year investigation into state oil company Petrobras — and a plot to prevent PT from getting re-elected in 2018. Backed by American actors such as the US Department of Justice and the Atlantic Council,15 it was hailed in the press such as The New York Times for removing corruption from Brazilian politics, while failing to acknowledge US’ involvement.16 17 It mostly targeted politicians on the centre-left and provoked Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment in 2016.

No doubt the biggest ‘success’ of Lava Jato, however, was Lula’s imprisonment. Lula spent 18 months in jail after being found guilty of corruption in 2017, preventing him from running in the 2018 election. Meanwhile, Jair Bolsonaro, once a fringe candidate of the far-right Social Liberal Party, became a vessel for the Brazilian people’s frustrations with PT. His popularity abroad was also rising — the Wall Street Journal endorsed him as a candidate, stating that “he is a conservative populist who promises to make Brazil great for the first time.”18 When elected in 2018, President Donald Trump congratulated him on his win.19

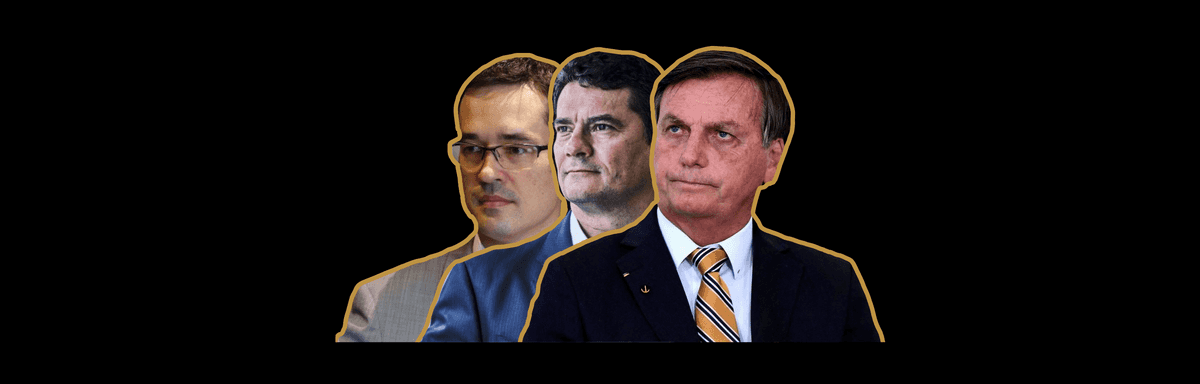

In 2019, Lula’s convictions were annulled, after he was initially sentenced to more than nine years in prison. The Intercept leaked Telegram messages between the head judge of Lava Jato and Bolsonaro justice minister, Sergio Moro, and prosecutors of the case such as Deltan Dallagnol, revealing that he had colluded with them to rig the 2018 election, and collaborated with US authorities.20 Shortly after entering office, Moro and President Bolsonaro visited the CIA Headquarters together.21

“They did not imprison a man. They tried to kill an idea,” Lula said upon his release.22

Electoral Scepticism

Background

With Lula’s charges dropped, his popularity remained relatively intact among his supporters.23 Bolsonaro pushed a heavy campaign expressing concerns about electoral fraud over the years, sharing unsubstantiated claims that Brazil’s electronic voting system was susceptible to hacking.24 Unlike past right-wing candidates in the country, Bolsonaro rejected traditional legacy media for his campaigns in 2018 and 2022, favouring Twitter, TikTok, and in particular, non-moderated and encrypted messaging platforms such as Gettr, WhatsApp and Telegram.

According to an overview of disinformation narratives in Brazil conducted by the Igarapé Institute,25 the most prevalent campaigns called to:

- Reduce trust in the electoral system

- Target democratic institutions

- Discredit and diminish the influence of political opponents

- Influence core supporters to take action

In 2020, as COVID-19 ravaged Brazil and claimed more than 600,000 lives, Bolsonaro shared conspiracies about hydroxychloroquine being a miracle cure, delayed vaccine offers and oxygen supplies in hospitals. As a campaign strategy, he curated his own ‘outsider’ status on several topics, from public health, environmental policies, gender issues, and LGBTQ rights to the election, mobilizing his supporters and allies against the imagined enemy — a strategy familiar to the extreme right globally, from Italy’s Giorgia Meloni to Hungary’s Viktor Orbán.

In July 2021, he appeared on a two-hour livestream on YouTube and said that voting machines were hacked, showing footage of people complaining that the machines would not let them vote. Later in September, at a large evangelical rally, he stated, plainly: “I have three alternatives for my future: being arrested, killed or victory.” In September 2022, his campaign launched a website called “Bolsonaro’s Inspectors” (Fiscais do Bolsonaro), where supporters could sign up to inspect the voter machines.26

A new cabinet and allies

During his 2019-2022 presidency, he formed a cabinet with the help of his second son (“02”) Carlos Bolsonaro, called the Office of Hate, intending to spread misinformation and attack media outlets who criticised him. While Jair Bolsonaro has denied the existence of such digital militia, Brazilian reporters and former ally Joice Hasselmann have leaked that it was used to spread rumours attacking the PT. For instance, in 2018, the Office of Hate said that PT’s Fernando Haddad was plotting to share a ‘gay kit’ in schools to promote homosexuality among children.27 In 2020, Bolsonaro said he would veto a bill — Bill 2630 — that would regulate the use of fake news on tech platforms.28

The Bolsonaro family’s disinformation campaign didn’t end there. In 2021, Eduardo Bolsonaro attended CPAC Brazil, a conservative gathering imported from the American far-right. While there, he met with Matthew Tyrmand, a board member of Project Veritas, a conservative group known for their use of spies against left media organizations and for spreading falsehoods about the use of ballots during the 2020 US election. During Eduardo’s speech at the event, he expressed that Brazil would benefit from an alternative to Project Veritas.29

The 2022 election

Bolsonaro's catastrophic mishandling of COVID and counter-protests meant that his popularity was dwindling. In the first round of the 2022 election, he fell behind Lula by 5 million votes, gaining 43.20% to his opponent’s 48.43.30 A day later, Steve Bannon appeared on his podcast, War Room, to say that it was ‘mathematically impossible’ that Bolsonaro was behind.

At the end of June, ex-Fox News host Tucker Carlson met with Bolsonaro for an interview in Brasília, stating that his initial election was a ‘miracle.’

In July 2022, three months were left for the election, and Bolsonaro ramped up his offensive against Lula and the Workers’ Party, all while hinting at a future stolen vote. On the 5th, he held a meeting with ministers and senior officials at the Planalto Palace in Brasília. “[They’re] setting everything up for Lula to win in the first round,” Bolsonaro said. “It’s a fraud. I’m going to show you how and why.”31 On July 18th, he met with foreign ambassadors where he attacked the Supreme Electoral Court, the security of Brazil’s voting system, and denied wanting to stage a coup.32 “People who owe favours to them (da Silva and his Workers’ Party) do not want a transparent electoral system,” he said.

The Online Bolsonarista Front

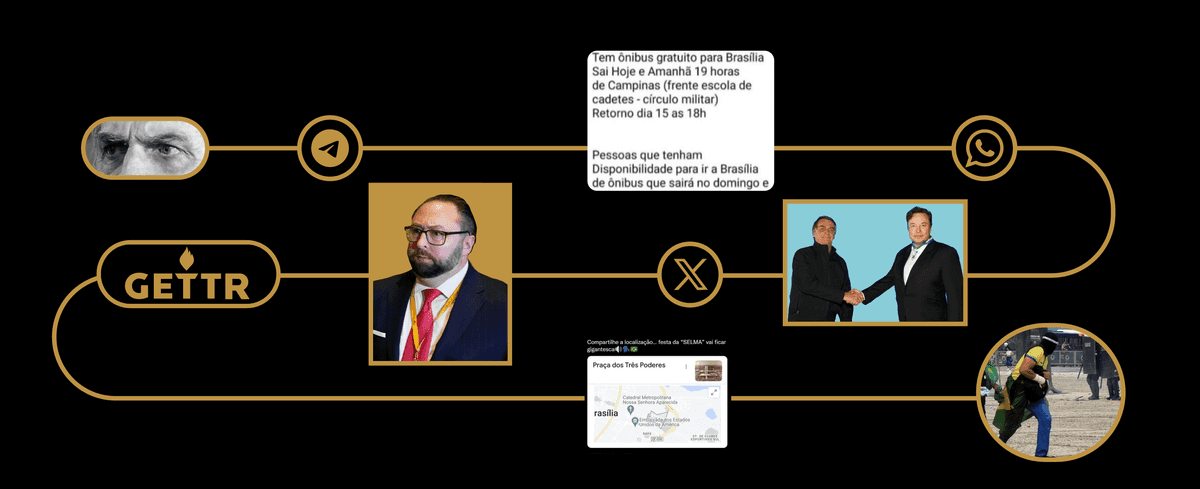

After an incredibly tight race, Lula was elected on 30th October 2022 with 50.9 percent of the vote, bringing hope to progressive forces of the world. Bolsonaro supporters, who had been planning on Telegram and WhatsApp since early October, set up blockades in front of highways and roads — which helped them establish camps outside of military bases. Meanwhile, Bolsonaro, usually a vocal social media presence, was silent. The hashtags #manifestacao, #BrazilWasStolen and #BrazilianSpring were shared widely on Gettr and Twitter, as his fans called for Lula’s imprisonment.

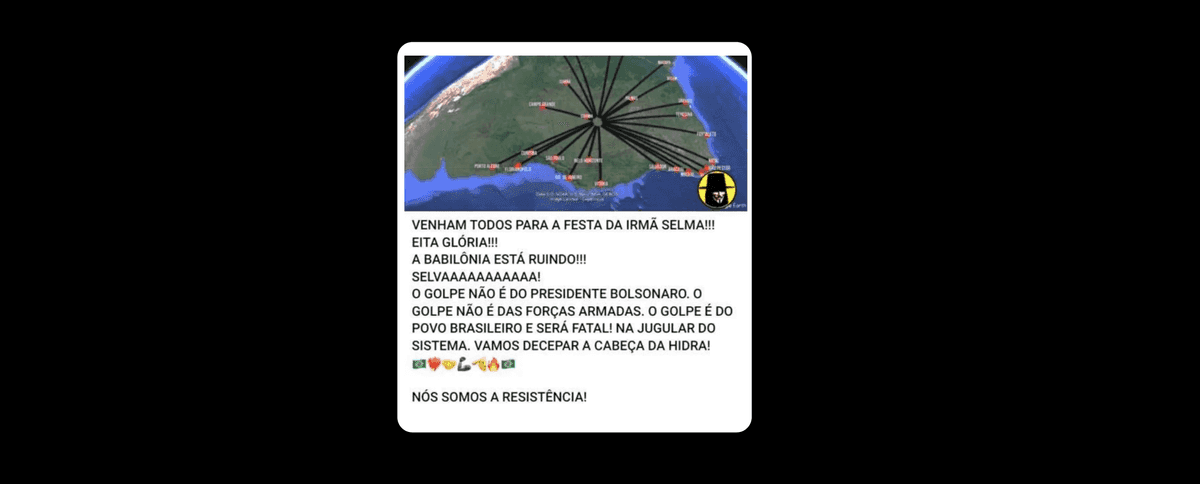

Few countries use WhatsApp quite like Brazil, and the far-right is no exception. In the months and days before the coup, groups used coded language to plan and mobilize the military, young conservatives, Neo-fascists and regular Bolsonaro supporters (‘WhatsApp Uncles’). First, ‘Selma’s Party,’ a reference to the military greeting ‘selva,’ was organized, calling people to come to the capital dressed in green and yellow.33 Then, a ‘Beach Trip’ map was shared on a ‘Hunting and Fishing’ Telegram channel, displaying 43 locations where attendees could board buses to Brasilia.

In the days leading up to the elections, Bolsonaristas shared false facts online. Analysis conducted by Agencia Publica revealed that from the 50 most widely shared political images circulating in 347 groups, 56 percent were misleading.34 In November 2022, Elon Musk fired his Brazil content moderation team and in early December said it was “possible” that Twitter favored left-wing candidates. In the past, Bolsonaro has referred to Musk’s acquisition of Twitter as a “breath of fresh air.”

It also seems there was a bilateral relationship between the Reactionary International’s social media platforms and other activities. Gettr, founded by Trump’s former advisor Jason Miller, which gained a major boost in business from Brazil’s users, sponsored the last two Brazilian CPACs and two regional conservative events called Brasil Profundo (Deep Brazil).35

The use of digital warfare was not limited to social platforms, either. As of 2024, the Bolsonaro family has been implicated in an investigation launched by the federal police for using Israeli spyware, FirstMile, to snoop on 30,000 people and hundreds of political opponents.36 37 Similar software, such as Pegasus by Israeli cyber-intelligence firm NSO Group, has been deployed in Mexico and El Salvador.

Friends in High Places

Addressing journalists following the coup in Brasilia, Lula said that “many people were complicit in this … many people in the military police were complicit. There were many people in the armed forces here inside [the palace] who were complicit”

Indeed, the coup would not have been made possible without a carefully planned network involving (a) an active conservative military base, (b) wealthy libertarian businessmen, and (c) famous evangelical leaders.

First, military members and by extension, the police were added to the group chats planning the coup —Bolsonaro’s cabinet was full of military chiefs and officers, such as Hamilton Mourão and Braga Netto. At the site, echoing the January 6 insurrection,38 police officers were found taking selfies with Bolsonaro supporters while they ransacked Congress, even accompanying them to the governmental buildings.39 The Brazilian Intelligence Agency sent out several alerts about the protestors, some days before the riot, which the Armed Forces and the Institutional Security Bureau ignored. The Presidential Guard, Col. Paulo Jorge Fernandes da Hora, was filmed arguing with the Military Police to stop them from arresting the protestors.

During Bolsonaro’s presidency, he stripped the Amazon land of its protections, leading to record-high deforestation and unprecedented attacks on Indigenous land rights. Big Agro — agricultural lobbyists, think tanks such as Pensar Agro, and wealthy businessmen — has been supported by global investors such as BlackRock, German Allianz, BNP Paribas and JPMorgan, and bolstered by Bolsonaro’s pro-market regime.40 Following the coup, reporters revealed that agribusiness lobbyists had financed some of the 100 buses that transported protestors to Brasilia from across the country.41

In the US, the Christian Right managed to gain power fighting against feminism, gay rights and the state — a path which was closely followed by Brazil’s Evangelical leadership. Famous evangelical figureheads, such as Silas Malafaia, a pastor and televangelist, sent the public to support Bolsonaro. Bolsonaro’s evangelist-nationalist slogan, “Brazil above everything, God above everyone,” incited crowds42 to fall back on religious imagery during the insurrection,43 believing they were carrying out the fight between “good and evil” in their fight against Lula.

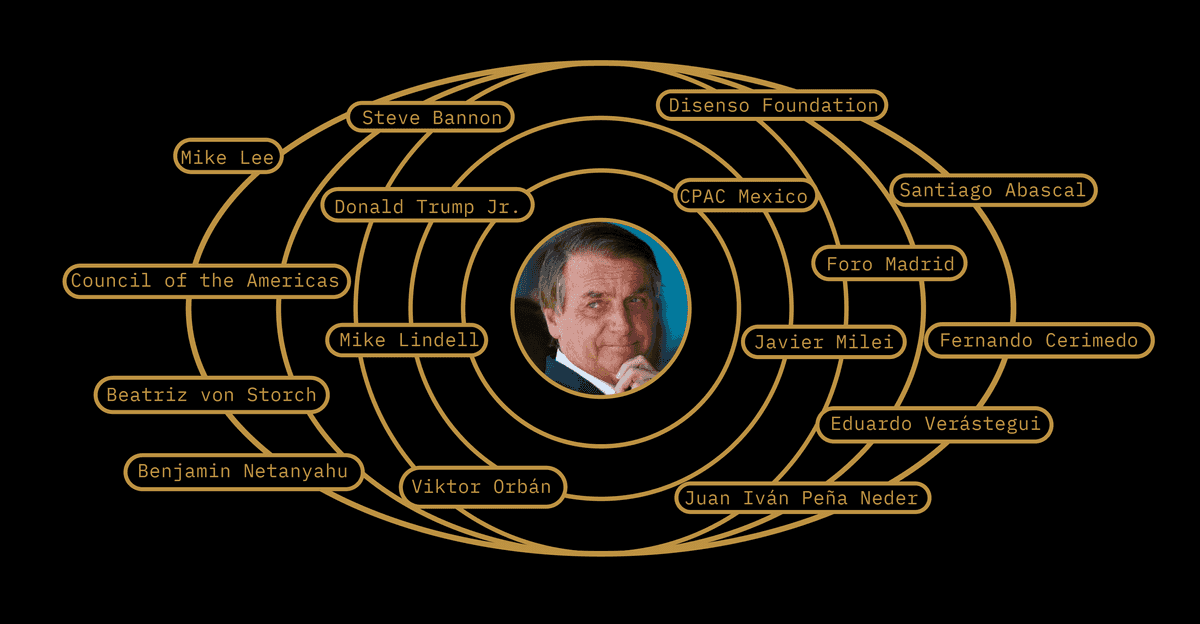

Bolsonaro’s International Network

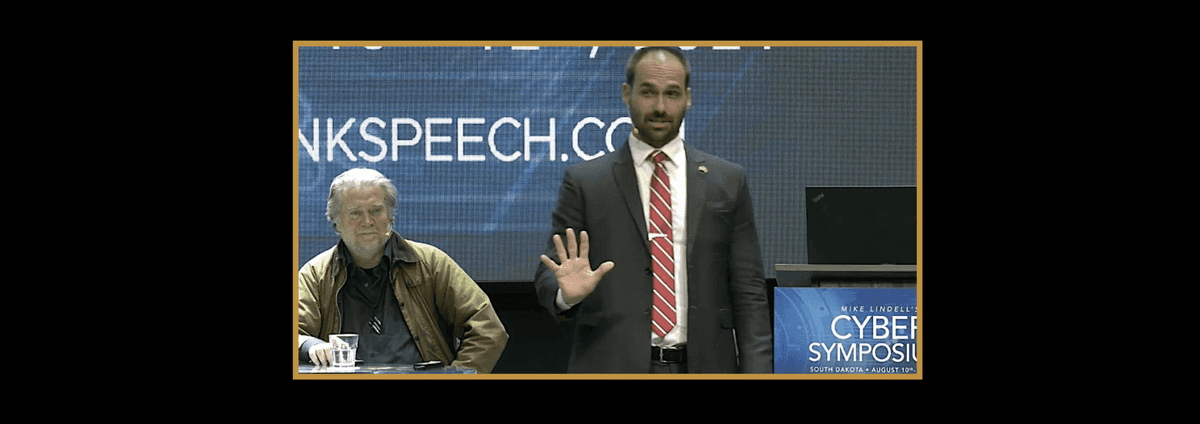

The fight against “Bolsonarism” extends far beyond Bolsonaro himself, his local allies or even the borders of Brazil. During his presidency, Jair cast a wide net for his extreme right collaborators, who shared his penchant for authoritarianism, racism and homophobia. His son, Eduardo, proved to be an essential link to the global far right at two key events: CPAC Mexico 2022 and US election-denialist Mike Lindell’s Cybersymposium 2021.

At CPAC Mexico on November 18-19, the first event of its kind to unite Latin America’s conservatives in Mexico City,44 he delivered a speech about the need to create a global conservative movement. In the Santa Fe event space, conservative actor Eduardo Verástegui, Mexican Republican Juan Iván Peña Neder, Steve Bannon, and notably, Argentina’s Javier Milei were in attendance. At past CPACs held in Brazil, he met with Jason Miller, Donald Trump Jr., and Mike Lee.

Another key Argentine Bolsonaro supporter is consultant Fernando Cerimedo. Days before the 2022 election, he tweeted “This Sunday, the world will know everything that is happening with the elections in Brazil. Censorship and fraud have silenced an entire country. #BrazilWasRobbed.” When Bolsonaro lost, he live-streamed to more than 400,000 people, arguing that the older ballot box models in Brazil had not undergone appropriate security tests.

In Europe, Bolsonaro has ties to Germany’s Beatriz von Storch of the far-right AfD party,45 Hungary’s Viktor Orbán whom he has referred to as a ‘brother,’ and Spain’s conservative VOX party leader, Santiago Abascal.

Eduardo was also involved with Foro de Madrid, an organisation created by VOX. In 2020, he signed the Carta da Madrid, a charter designed to unite conservatives in the Ibero-Americas against the “totalitarian regimes of communist inspiration.”46 Foro Madrid ended up condemning the violence during the January 8 riots, while attacking the ‘double standards’ of leftist leaders.47 In late 2023, Jair Bolsonaro’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs Ernesto Araújo, joined Vox’s conservative think-tank, Disenso Foundation, as an international advisor.48

Jair Bolsonaro additionally kept close ties with Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu during his presidency — opening up borders for arms, technology and trade. In 2019, Brazil opened an office in Jerusalem for Apex-Brasil, the Brazilian Trade and Investment Promotion Agency.

In 2019, at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Bolsonaro gave a keynote speech stating that he would open up Brazil’s global economy, most notably access to the Amazon. In January 2020, Paulo Guedes, Bolsnaro’s finance minister who trained at the University of Chicago and is associated with the Millenium Institute, spoke at the WEF about Brazil’s industry and the environment. "Nature's worst enemy is poverty. People destroy the environment because they need to eat," he said.49 The Council of the Americas, a think tank founded by banker David Rockefeller, has praised his approach to Brazil’s economy through their publication, Americas Quarterly.50

At the 2021 Cybersymposium in South Dakota, Eduardo was introduced to Bannon’s network and was inspired by his ‘stop the steal’ approach to politics. There, he spoke about how his father had exposed hackers who got into Brazil’s electronic voting machines, to a crowd of conspiracy theorists. At the end of his speech, he gifted Lindell a MAGA hat signed by Trump.

US support was consistent after the insurrection. In March 2023, Turning Point USA hosted Bolsonaro in Miami51 with Charlie Kirk, to a lively crowd that shouted ‘fraud!’

After Bolsonaro: Challenges to Brazil’s Democracy

Following the January 8 coup attempt, the Lula administration promptly stepped in with legal measures to investigate the rioters, congressmen involved and its financiers. The case was brought to court almost immediately, and Bolsonaro was banned by the Federal Supreme Court from running for 8 years due to “bombarding” voters with disinformation and destroying the credibility of the electronic voting system.

Later, a draft of the coup — which set out a list of conditions to overthrow the election — was found in the home of his former Minister of Justice, Anderson Torres, who was subsequently arrested.52 In the days after the coup, tens of thousands of protestors organized large pro-democracy rallies, from São Paulo to Porto Alegre,53 and the riots were condemned by global progressives such as Gustavo Petro and Jeremy Corbyn.

In February 2024, the federal police launched a raid against Jair Bolsonaro and his inner circle54 and seized his passport. Court documents revealed that he had edited a decree in case he lost the 2022 election, pressured military chiefs to join the coup attempt and plotted to jail a Supreme Court justice.55

Although Bolsonaro is out, and is currently facing legal action and the coup was a failure, he made significant wins in terms of congressional power. Four years in office gained him a steady network of far-right politicians, influencers, a conservative military force, and more. Meanwhile, the Workers’ Party, Landless Workers Movement (MST), Unified Workers' Central (CUT), Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) and other social movements continue to fight for the rights and social equality of Brazil’s people — a necessary coalition against the global far-right.